Entertainment

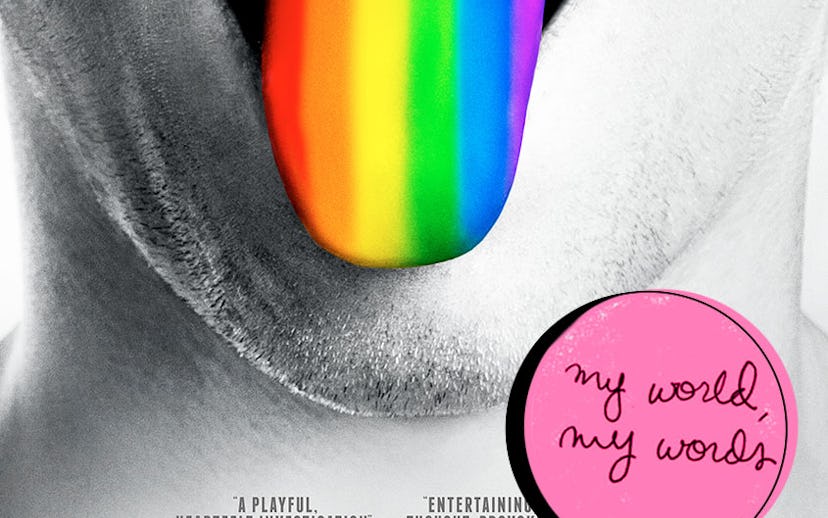

my world, my words: do i sound gay?

a simple question with a loaded answer

My World, My Words is a series of first-person essays featuring totally unique, inspiring personal experiences unlike anything you've heard before. The most interesting stories are also often the most overlooked, so we're on a mission to find them and share them with you. Written by people from all walks of life, these essays will move you in ways you might not expect—and that's the point.

The other day, my boyfriend and I had a back-and-forth about who was more gay. It was like that scene in The 40 Year Old Virgin where Paul Rudd and Seth Rogen do that “You Know How I Know You’re Gay?” bit, but with actual gay men. It was childish play, but something about what he said got under my skin. Does my history of going to “gay parties,” obsessive love for women in pop music, tragic icons like Judy Garland, and general mannerisms give my sexuality away? Does partaking in those activities mean that I’m more gay than my boyfriend if he doesn't? Why do I care so much about whether they do or don’t?

It wasn’t until I saw David Thorpe’s new documentary Do I Sound Gay? that I started to understand why I felt unsettled being the (possibly) gayer one in my relationship.

The premise of the documentary is complex in its simplicity: We’re all familiar with the effeminate sounding “gay voice” and the stereotypically “gay” things a character on, say, television does. So, why do these qualifiers often rub a person the wrong way—even slightly or subconsciously?

I sat down with Thorpe and he told me, “TV and film have fetishized the ’S’ as a major gay signifier.” (Think: sssory or thorry.) A vocal coach explains to Thorpe in the film that the “gay voice” often comes with drawn out vowels, too. It’s theatrical. He added: “Then, of course, limp wrists and graceful hand gestures are a stereotype that is very much with us.” We’ve seen these characteristics blossom in the media over the past few years and they will continue to do so. Gay activist, author, and journalist Dan Savage (and subject of the documentary) explained to me over email that “There never was one way to be gay. There were always lots of different ways to be gay—drag queens and leather guys and clones and religious gays and gym bunnies and A-Gays and suit-and-tie gays and musical-theater queens and on and on, sometimes with significant overlap between the groups.” Yet these types, if you will, fall into a hierarchy; some are praised on a pristine pedestal while others are dismissed and marginalized. Thorpe’s question of whether he sounded “gay” reflects that hierarchy and, subsequently, my perturbed feelings.

* * *

I’ve never believed I’ve sounded particularly gay. My voice isn’t terribly feminine, but it’s also not masculine. Unlike Thorpe, who “grew up in a time when you felt like you had to be more careful about who you came out to,” I’ve never tried to hide. I actually relied on my voice and mannerisms to do the coming out for me, instead of making the big declaration to my family, friends, and ex-girlfriends that I’m gay. It wasn’t until after I moved to New York (cliché, I know) and started to shamelessly explore who I was as a gay man that the annoyance toward the effeminate started to creep in. Maybe it was because I had fallen into a circle of particularly neutral to more masculine-leaning guys who called each other variations of “Miss Girl” and camped it up as a tool used to emphasize a point, rather than a day-to-day performance. My environment fostered what Dan Savage says is “an internalized homophobia.”

Thorpe wonders aloud to Savage in the film why gay men sometimes put down other gay men. “Misogyny,” Savage replies. “They want to prove to the culture that they’re not not men—that they’re good because they’re not women. They’re not like women, they don’t want women, they don’t want to sleep with women, they don’t want to act like women. And then they’ll punish gay men who they perceive as being feminine in any way.”

Woah. Like, WOAH. You’d think this kind of attitude wouldn’t prevail in today’s culture, but Thorpe told me, “One thing that’s been really interesting to me in making the movie is finding out that even young people like yourself still feel somewhat oppressed by this kind of masculine ideal, that sometimes people in the gay community are trying to find.” Indeed, I’m not the most masculine of guys, and even I was initially turned off by my now boyfriend’s voice.

* * *

Idolizing the adonis in gay culture isn’t going to go away anytime soon. It’s ingrained in the homosexual cultural DNA and has decades of homoerotic art, Hollywood tropes, and a misogynistic past behind it. What we can do, and what Thorpe hopes to see is something Dan Savage told me: “Gay men just need to embrace the diversity within our own community and stop policing each other for masculine traits or feminine traits, authentic gayness or non-authentic gayness (there’s nothing inauthentic about having a d*ck in your mouth, regardless of how else you choose to live), assimilationist or separatist, etc.”

There is no such thing as a fundamentally “gay voice.” Thorpe says it’s “shorthand for the stereotype.” With that in mind, the question of how gay someone is or how gay someone sounds is packed within a larger question of what it means to be gay. I don’t have the answer. David Thorpe and Dan Savage don’t, either, but we can begin by coming to terms with the gay voice. As Thorpe told me: “It’s the final act of sealing the deal.” I am who I am. We are who we are.

Do I Sound Gay? opens today, July 10.