Entertainment

Netflix’s ‘Making A Murderer’ Will Draw You Into Its Dizzying Mystery

the true crime docu-series debuts tomorrow

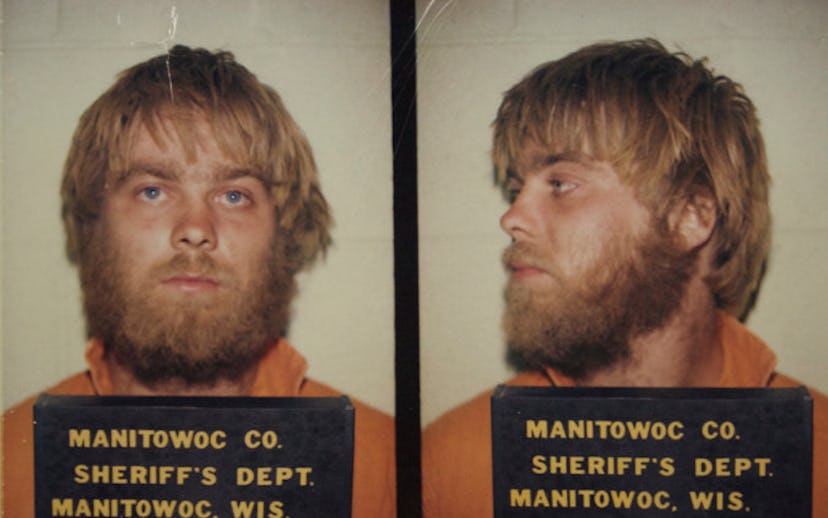

Despite Netflix’s full roster of original programming—which has featured a prison drama, a political thriller, screwball comedies, and modern-day superhero dramas—one genre so far has been missing from its slate of shows: the docu-series. Making a Murderer, a ten-part true crime series that hits the service tomorrow, fills that void. Set in the sleepy Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, Making a Murderer is an exhaustive, expansive exploration of the case of Steven Avery from filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos.

The show opens in 2003, when Avery was released from prison after serving an 18-year sentence for a crime he didn’t commit. A seemingly dim guy from the wrong side of the tracks, he spent most of his early years in and out of trouble, he was o stranger to Manitowoc police (they viewed him and his larger family as slightly more than just a criminal nuisance). When a local woman was sexually assaulted and beaten in 1985, the cops immediately figured Avery for the crime—this, despite the fact that there was little evidence placing him at the crime scene, the victim's memory was hazy, and Avery was steadfast in his claims of innocence.

Nearly two decades after his trial, DNA evidence exonerated Avery and proved that another local man, already serving a criminal sentence for another violent sexual assault, had committed the crime. It was a classic case of a corrupt, biased police department fingering the wrong guy. Ultimately, the case gained attention after Avery opened a $36 millon lawsuit against the county police department and sheriff. Suddenly, the man was the face of the state’s efforts to reform a broken criminal justice system. Avery suddenly became a local celebrity—and earned the ire of the local police yet again.

That’s why the area was shocked once again by the news of the disappearance of Teresa Halbach on Halloween in 2005. A freelance photographer for Auto Trader magazine, Halbach was last seen at Avery’s property (his family owned an auto salvage company). Suddenly, Avery was the prime suspect—particularly when Halbach’s car turned up at his home.

Even though he maintains his innocence, Avery’s case doesn’t look very good. Pieces of DNA evidence make it easy to point him as Halbach’s killer (his blood was found in her car, her key was found in his trailer.) But there are complications, too, which lead many to believe the local police department framed him in order to avoid the large payout as a result of his civil case against them. There’s little to suggest that Avery had a motive in the case. Why would this guy, fresh from prison and a high-profile figure as a result of his exoneration abduct a woman he had met several times, rape her (as his nephew, the state’s prime witness, recounts), and dispose of her body? But is that easier or more difficult to believe, than a major conspiracy on the part of local law enforcement and the state to get revenge on an innocent man who embarrassed them? This is the central question and attraction of this series.

Making a Murderer seems to hit all of the right notes, offering up a juicy, complicated murder case with all of the frills of other recent pop-culture hits. Here we have some of the white trash fetishism of True Detective, the Midwestern accents of Fargo, and the convoluted plot of Serial, in which a man was arrested and convicted of a crime he claims he didn’t commit. (A not-really spoiler alert: Avery was convicted of Halbach’s murder in 2007.) Ricciardi and Demos, who started work on the project in 2005, examine all sides of the case in an intricate manner, offering a look at the ways in which the police harassed the Avery family, nearly forced a confession out of Avery’s nephew, Brendan, and how the case became the subject of a media frenzy.

While the series unfolds like a long Dateline episode (Serial certainly didn’t establish the true crime genre, offering twists and turns and varying perspectives, but it definitely legitimized the pulpy, lowbrow concept), it makes an attempt at prestige television. Documentaries, of course, have played roles in exonerating innocent men stuck behind bars, although it’s not clear that is Making a Murderer’s intention (only the first four episodes were available to reviewers). Fans of Serial and HBO’s The Jinx will no doubt take to the Netflix series with a similar obsession, and one expects its audience to feel like amateur sleuths who can, given the evidence seen in the documentary, crack the case.

But unlike those other true crime tales, the real-life story has, it seems, concluded. What Making a Murderer excels at is defining a mood and reiterating the theme that Serial hit home: When there are a dizzyingly number of points of view and perspective, we create wild narratives that attempt to explain the unexplainable. Sometimes, our quest to know the truth results in crafting our own versions to placate our own needs, and others are caught in the murky waters where truth and fiction intertwine.