Entertainment

Eileen Myles’ Poetry Album Is Sloppy, Sexy, And Overly Intimate

“Fuck, it’s so hard”

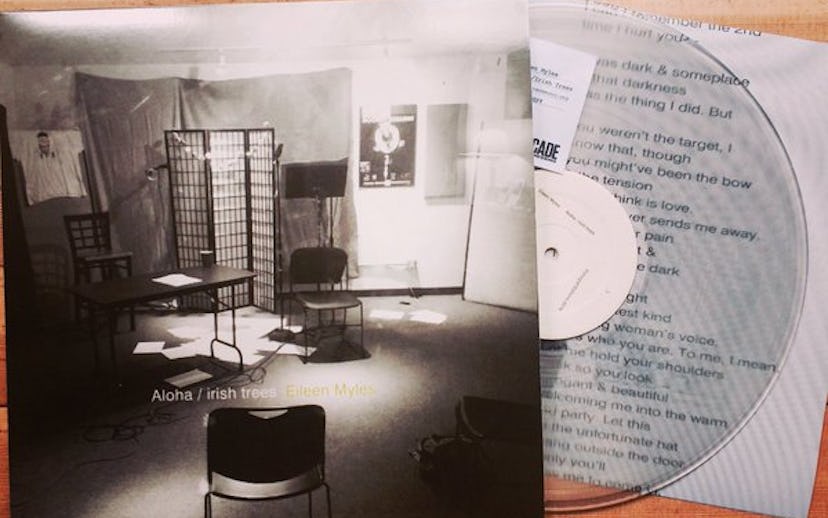

The 36 poems included in the new Eileen Myles poetry record, Aloha / irish trees, are either “new” or “pretty old,” as the linear notes inform us, with no in-between. It’s fitting that the poems on the record be this extreme combination, as it's something that exemplifies the idea of a poetry record itself: Though the concept of a poetry record was first introduced in the 1950s through Caedmon Records, the idea that someone in 2016 might want to create a vinyl record of poems feels somewhat novel.

Still, the immediate question that comes to mind when hearing “vinyl record-only poetry press” is, “why?” In a way, it’s a testament to Myles’ popularity that sentimental objects bordering on poetry kitsch can now be made. But Jeff Alessandrelli, the founder of the record-only press, called “Fonograf Editions,” defends his choice to begin the press with a Myles record, explaining that he’s been a fan long before her recent mainstream popularity. Besides, Myles is only the beginning of the press’ future. Providing the Myles record peaks interest, he plans to release Harmony Holiday’s The Black Saint and the Sinnerman by early fall.

So who would buy a record of a well-known or little-known poet reading their poems on vinyl? The most obvious answer is someone with a record player, of course. Maybe someone who likes poetry. Or music. Or, in the case of Aloha / irish trees, someone who really, really likes Eileen Myles. And there still could be a fan of all three. The truth is, the audience for a record like this is rather slim. Still, the worth of a record clearly doesn’t lie in market value, and the press’ founders certainly don’t seem delusional about how much traction or attention this kind of art object is going to receive. The audience doesn’t necessarily seem to be the point. This is made clear in the first minute and a half of the record itself, where Myles reads a poem, messes up, tries again, messes up again, and says, “Fuck, it’s so hard” before reading the whole poem from the top.

What the record seems to be concerned with is an experience, and an exclusive one at that, though not too exclusive since it can be easily purchased on the internet for $16. But when you can put aside the marvel of the object itself, the experience is definitely there, and it’s quite a good one. If one were going to make a vinyl of poetry in the digital era, Myles is the ideal choice for such a project. Her poems lend themselves perfectly to being read out loud. Besides for coming up through spoken word poetry and the St. Mark’s poetry project, her thick Boston accents relishes the words, making them juicy and tart with the kind of addictive rhythm that gets the lines stuck in your head so you want to listen to the poems again. The various sounds of the record—the squishing of her spit, the breathing punctuating the poems, the swallows, the mistakes, the repetitions, the occasional sniffs, and slurring—make it more like music than poetry. They also make it sloppy, sexy, and overly intimate; which is exactly suited to Myles’ poems, describing the city as “juicy and bloody at night” or talking about a “kind of furless pussy,” with titles like “You” and “May 29,”as if we’re in Myles’ diary or being addressed by it.

In “Therapy,” Myles declares, “I like therapy because I don’t need my glasses/ I can sit there naked like the animal I am.” Listening to the record is an opportunity to engage with poetry with no glasses on, like sitting at an incredibly informal reading or performance, where Myles is trying to be as transparent as possible. Much like a reading, the poems on the record are, at times, contextualized or given short one- or two-sentence intros. At one point, Myles unscrews a bottle of water and drinks.

For those concerned with the difference between listening to the record and just reading Myles’ poems on the internet, the poems on the record are arguably new poems, even those that have been previously published. They sound different the way Myles reads them, often as if she is encountering her own work for the first time. One poem is missing its ending, another has multiple extra words. At the end, there is a short recording of whining, creaking trees, presumably the sounds of the forest the Aloha / irish trees is recorded in. Some might call it sentimentality, or a fetish art object, but there’s no denying that the record is cool, maybe even authentic, despite all its attempts to come across as so. Though the market for the record is small, those who buy it would surely enjoy it, should they find the time (and the record player) to listen to it.