Fashion

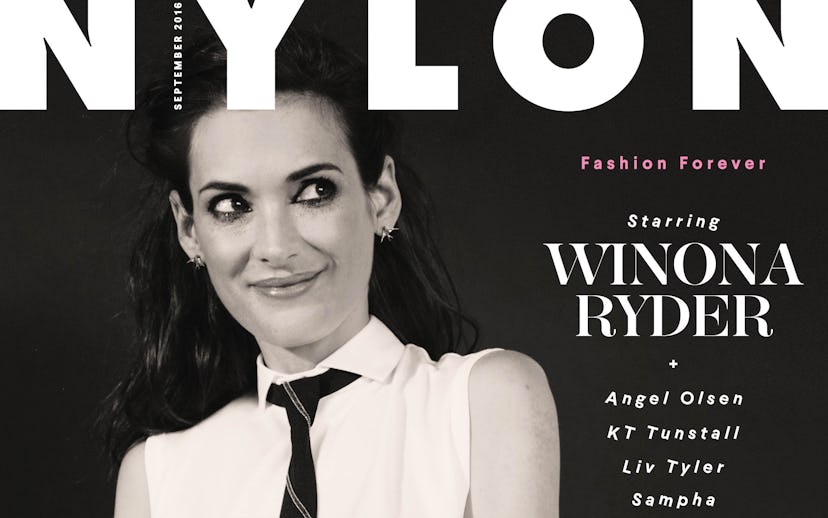

Winona Ryder Is Our September Cover Star

#WinonaForever

The following feature appears in the September 2016 issue of NYLON.

It’s very likely that Winona Ryder is a time traveler from another decade, but it’s tough to pinpoint which one. Possibly her flux capacitor got jammed on shuffle and she’s been bouncing between timescapes ever since, taking a pinch from this era and that. She’s a high-intensity mix of commune-educated ’60s, rocker-goth ‘90s, and something sweepingly, intellectually Victorian—all of which swirl together on this particular late-summer afternoon of free-ranging conversation inside a weirdly stripped-down room at Hollywood’s Roosevelt Hotel, and surely on every day of Ryder’s life.

At 44, there’s a sense about her that despite whatever self-doubts she might’ve struggled with in the past, she’s at peak power now. In September, she’ll make a cameo in the much-anticipated Author: The JT LeRoy Story. And audiences are still buzzing over Stranger Things, a meticulous slice of ’80s Spielbergian nostalgia that debuted on Netflix in July, and which has benefitted greatly from Ryder’s revitalization: She pounces all over the role of Joyce, a worked-to-the-bone single mother whose son is kidnapped by supernatural forces.

To most people, though, Ryder’s face is a portal to the ’90s. (Her friend Marc Jacobs capitalized on the fetishization of that decade when he tapped her to model in his latest beauty campaign.) Even today, with her long wavy hair and delicate lines etched around her eyes, it’s easy to summon that pixie haircut and those brick-red lips, or the lovestruck expression as she snuggled up to then-boyfriend Johnny Depp in so many now-classic images from the era.

Click through the gallery to read the rest of the feature.

Top, tie, pants, and belt by Brunello Cucinelli, Ryder's own earrings.

The daughter of hippie writers Cynthia Palmer and Michael Horowitz, Ryder was named after a little town near her family’s Minnesota farmhouse, where they lived before moving to a Northern California commune. It was a time when parents of a gifted child still viewed Hollywood as a ravenous wolf from which to protect their daughter, not an opportunity for a future family reality show. Actors didn’t worry about their platforms, but they still risked burnout or worse from drugs and anxiety—all of which Ryder’s battled, sometimes in painfully public ways. Throughout it all, though, she’s been game to poke fun at herself. Exhibit A: the 2002 W cover on which she wears a “Free Winona” tee. Last year, model Sarah Snyder echoed that cheekiness when she wore a T-shirt featuring her own mug shot to her shoplifting trial. Recalling the media frenzy that surrounded Ryder’s own run-in with the law, it’s not surprising that she’s not interested in returning to that time, or even just before, no matter how much we all might miss the golden era when alternative was queen, quick to serve some jovial side-eye to the Spice Girls, MTV’s Spring Break, and the like. How did she get through it? “You just do,” she says. “In the scheme of things, there are much bigger problems to worry about.”

When asked whether she’s aware that she’s a goth icon, Ryder pauses, momentarily speechless. “I feel kind of proud, I guess, but I can’t take full credit,” she says. She cites The Cure’s Robert Smith, but that’s music; she was the queen purveyor of ’90s goth vibes in film (second place: Christina Ricci, who coincidentally starred with Ryder and Cher in Mermaids, a solid contender for a Heathers: The Musical- or Beetlejuice 2-style treatment). “It’s flattering to me. It was a long time ago, but I’ve always felt sort of attached to that time,” Ryder says. “I was just listening to [The Cure’s] ‘Pictures of You’ because I have these old mixtapes that I don’t know what to do with—I’m like, ‘How do I transfer them?’ I still have a tape deck.”

Countless young actresses working today are indebted to the groundwork Ryder has laid, but one of her most vocal fans, Emma Roberts, brings a similar America’s sweetheart-meets-witchy energy to her roles in Scream Queens and American Horror Story. “She made being strange both beautiful and cool,” says Roberts, who watched the savagely satirical Heathers in preparation for Scream Queens, and claims to have all of Ryder’s lines from Girl, Interrupted memorized. “She’s forever a trendsetter without even trying.”

Dress by Giamba, cuff by Erickson Beamon, Ryder’s own T-shirt.

What Ryder doesn’t have in common with her millennial cohorts is the pressure to perform on social media. She doesn’t have a single account, but that doesn’t mean she judges those who do. “I know it can be a fantastic tool,” she says, “but do you have to have all the crazy people? Is there a way to just…?” She trails off.

No, there isn’t.

“Yeah, I’m just a very private person,” she says.

By the way, call her goth, but don’t call her grunge, her relationship with Soul Asylum’s beflanneled Dave Pirner aside. “That whole label was a little bit weird. I somehow got sucked into that. Not by choice, because I was actually listening to Judy Garland albums,” she says.

The clamor of ground-zero Hollywood leaks in from the open windows of Ryder’s hotel room. She tunes out the noise as she paces around the room, searching for a menu to order eggs and hash browns. She’s only had tea all day, and the unrepentant night owl woke up late. “We’re all nocturnal,” she says. “It runs in the family.”

After she orders, Ryder settles into the room’s monstrous leather couch. Slightly hunched in a faded black Leonard Cohen T-shirt, black jeans, and oxfords, clutching a Václav Havel book, Ryder speaks with bubbling admiration for the noted writer and former leader of the Czech Republic. “Václav Havel has always been a hero of mine,” she says. “I underline so much of what I read. It’s awful—I can’t lend my books to people because I don’t know if I’m revealing too much about myself by what I’ve underlined, or if it’s just plain distracting for them.” She launches into a story about how she just missed meeting the playwright in person, that cute creak in her voice that’s always made her sound a bit quaint or elderly or unhinged (or all three) punctuating the anecdote, which meanders from her dad’s archival work for Timothy Leary (also Ryder’s godfather) to the time Woody Harrelson, formally invited by Havel, was nearly kicked out of a Czech opera hall because of his crying newborn.

Perhaps her most distinct quality is her ability to talk, in a way that’s almost a lost art, stringing together long sentences packed with knowledge, anecdotes, and philosophical speculations, a style of communicating that she likely learned from her parents—the kind of folks who would choose a counterculturalist acid sage to be her spiritual guide. Her mind engages in the ultimate wanderlust; it’s a joy to strap in for the ride.

From the start of her career, Ryder’s been looking back in time. When she first appeared in Lucas as a teen wallflower in 1986, it wasn’t her contemporaries she looked up to but a mix of Old Hollywood and ’70s art film icons—Audrey Hepburn, Gena Rowlands (with whom she worked in Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth), and mentors such as Jason Robards. “I was perhaps a little unusual,” she says, in between bites of hash browns. “I really was always drawn to other eras.” Reading Jane Eyre for the first time as a teen, she wanted to transport herself to the late 1700s, until her parents dropped some knowledge about 18th-century plumbing and dental care. But Ryder still yearned, and yearns now: “I think actors, on some weird level, feel like displaced souls,” she says. “I have had a lot of conversations about this, and part of it just may be from steeping ourselves in the history of film and the things we’re drawn to, like period pieces.” Ryder has done her fair share of those—Bram Stoker’s Dracula, The Age of Innocence, Little Women—and nothing makes her brown eyes blaze more than talking about movies, be they tiny indies, blockbusters, documentaries, or Sundance winners.

Dress by Marc Jacobs, Ryder’s own earrings worn throughout.

Though we’ve seen glimpses of her over the past decade—most notably in a meta turn as an embittered ballerina deemed past her prime in Black Swan—Stranger Things delivers the first opportunity ever to sink into a Ryder performance drawn out over eight episodes. Created by the Duffer Brothers, the series provides the perfect vehicle: a character on the edge of falling apart who manages to demonstrate a secretly mighty resilience.

Ross Duffer, one half of the twin brother team, says that Ryder “brought this wild energy to the character, this frenetic quality,” which led them to write one of the show’s best scenes. In it, Ryder learns that her missing son is communicating with her through electricity, namely a tangled bundle of Christmas lights. As the lights blink in response to her questions about his whereabouts, “she takes us through the whole sequence of emotions—terror, confusion, and joy,” says Duffer, all while winking slyly at the absurd humor of the scene.

The Duffer Brothers found themselves a little scared of Ryder at times, but happily so. “We did not expect the intensity she brought to the role,” Matt Duffer says, recalling how Ryder often disappeared for five to 10 minutes before dramatic scenes, only to come back in another state. Indeed, Ryder’s performance is a physical and emotional wallop—she smashes phones, shakes with sobs, and plays up her small frame for every unnerving bit of baby-bird fragility. For Ryder, commitment to turning out Joyce’s every fear is what it means to work.

“Yeah, I’m kind of a bit old-school,” she says sheepishly, “which is good and bad, I guess. The only way I know how is to really go there.” At first Ryder was daunted by TV’s pacing, as the bulk of her acting experience is in film. But even with the pressure on, she was not willing to ransack her private life for the sake of a scene. “I don’t want people bringing up personal things. I think that can damage an actor, and I know a lot of people who have been incredibly hurt. There are things in my life that I’ve been through that I do not want to exploit. It’s hard, though, when it’s crunch time and you’re losing the light or we only have 20 minutes left. It’s weird. There are certain things that do make me cry, but I feel like they’re almost sacred,” she says.

Dress by Giamba, cuff by Erickson Beamon, ring on pointer finger by Atelier Swarovski by Rosie Assoulin, ring on ring finger by Laruicci, Ryder’s own T-shirt.

Ryder’s relationship to the camera and how much she’s willing to give is always a negotiation. In Girl, Interrupted, a passion project that she doggedly pursued for years until its release in 1999, Ryder remembers holding the operator’s hand under the camera during close-ups. “Literally, these are people that are closer to me than sometimes the director, sometimes another actor,” she says. “You work so closely with them, and it’s this weird thing with film because you have to be natural. You have to forget there’s a camera there, but there is also an element of choreography because you have to hit your mark. So you have to be aware but not be aware. I have to say, my guys got me through it. All of that emotion, and they knew instantly to support me.”

Ryder shows me one of her tricks: She lays her hands on her lap, palms up and open. “If you put your hands up, you feel vulnerable. It’s the little things. I learned that from Jennifer Jason Leigh when I was just starting out,” she says.

As much as Ryder melds with the camera (and its operators), there are times when she was so close to a part, she simply was that person. Case in point: Lydia, from Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice, one of her most iconic roles. “That was sort of what I looked like,” she recalls. “That was my hair—I was super pale. They really just put some powder on me.”

Burton, who’s tapped Ryder’s dark powers for numerous projects, including, most recently, a video for The Killers where she’s strapped to a spinning torture wheel, says that “she’s always up for anything I ask.” Even when she doesn’t see a trace of herself in the role. In Edward Scissorhands, she left her stock-in-trade behind to play a blonde cheerleader. “I think she would admit she didn’t relate to her character; she was tortured by these kinds of people at school herself,” Burton says. “So it definitely was a challenge, but she shaped it into something really emotional.”

Vest by A.F. Vandevorst, pants by Ann Demeulemeester, ring on right hand by Konstantino, ring on left hand by Erickson Beamon, gloves by Lacrasia.

As for those Beetlejuice 2 rumors, Burton cannot confirm or deny their validity: “I’ve talked to Winona and Michael [Keaton] about it. It’s something I really would like to do under the right circumstances, but it’s one of those films where it has to be right. It’s not the kind of movie that cries out for a sequel—it’s not the Beetlejuice trilogy. I do love the characters, so we’ll see. There’s nothing concrete yet.”

Though her former aesthetic has been co-opted for high fashion—Wes Gordon paid homage to Lydia’s girl-vampire hair at his spring show, and Jacobs name-dropped the character as a reference for his epic fall collection—it’s Jacobs’s campaign for his cosmetics line that captures Ryder now. Photographer David Sims shows her in rich, creamy lighting, her smoky eyes staring into the distance. Again, she radiates presence like she’s almost inside the camera. “She does not model the look; she gets into the role—and exudes it,” Jacobs said in a statement upon the campaign’s release. “A brilliant mind, talent, and physical beauty like no other.”

Part of what’s clear about Ryder in both Jacobs’s campaign and Stranger Things is that she doesn’t fear getting older. One night a few years ago, when she was up late watching TV, a movie of hers came on. “I can’t remember what channel it was or which one, but it was a ‘golden oldie’ and it was kind of great! It made me laugh,” Ryder says, tilting her head back into the couch. “I never really had any hang-ups about aging. I’m not trying in any way to be insensitive to the conversations about ageism going on, because I know it’s definitely a struggle. I think just, for me, part of it is probably having started so young and that desire I had—I was always hanging out with, or trying to hang out with, the ‘grown-ups.’” For as long as she can remember, Ryder has felt a deep connection to her elders. She wants to greet the future like an old friend. To which the future says: Winona, forever.

Clothing by Rodarte, cuff by Verdura. Hair: Suave Professionals Celebrity Stylist Marcus Francis. Makeup: Stephen Sollitto at TMG-LA.com using Diorskin Nude. Manicurist: Debbie Leavitt at Nailing Hollywood using Formula X in Atomic. Prop Stylist: Scott Horne.

NYLON’s September issue hits newsstands August 23. Buy it now (and receive a 15 percent discount off your next order!).