Entertainment

flashback friday: dancer in the dark

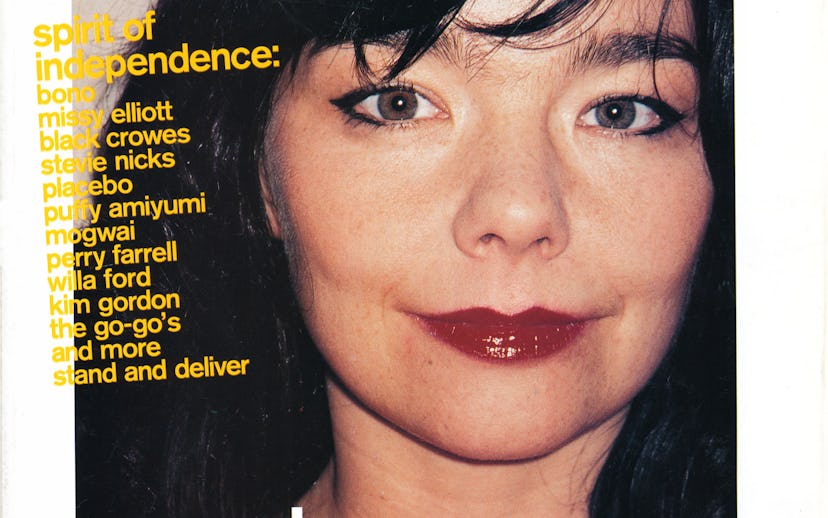

time travel to our june/july ’01 cover starring bjork.

Our weekly Flashback Friday just got a whole lot cooler. We're still posting some of our favorite covers from past issues of NYLON, but now you can go even more in-depth with our faves by reading the cover stories in their entirety! Yep--consider this your really rad trip down memory lane. Today we're celebrating Bjork's birthday (which was yesterday!) by flashing back to her June/July '01 cover story where she talked Vespertine, the swan dress, and Madonna with writer James Servin. She even poses with a swan in the photos lensed by Terry Richardson! Can't top that.

Following the acclaim of her all-stops-out performance in Dancer In the Dark, the controversial swan dress she wore to the Oscars, and now the release of her new CD, Vespertine, there's so much to ask Bjork. But at the moment, it suffices to reach for the most immediate question, and that's to ask her how she is right this second. "A bit under the weather from staying up all night," she admits. "Yeah, my friends and I went out to this place on the Lower East Side called Swim and stayed there until 4 a.m., dancing and drinking sea breezes. I don't really feel hungover. Yet."

In her mid-30s but humming with youthfulness, the impressive woman sitting across from me is gorgeous in an organic, inside-out way, radiating the kind of beauty a creatively fulfilled person exudes. She's got beautiful skin, tousled, long dark hair, and, for the final touch, she wears a blue dress with a high collar, long sleeves, and a train. In contrast to the powerful star-making imagery that surrounds her, Bjork in person has a very strong I'm-just-a-regular-Joe streak. There's warmth and remove; her eyes glisten as she smiles and shakes your hand. As she begins to speak, it's apparent that her cadence is quite different, a sort of Icelandic version of an Irish brogue by way of London, with Rs rolled out. She has a powerful take-charge presence, which is complimented by an air of openness and curiosity.

"It's about creating paradise on your kitchen table... or under it."

We're in the Cupping Room, a small cafe in Soho, drinking mochaccinos and sharing a plate of fruit and a side of baked Brie. It's a cozy, intimate place, a fitting backdrop for discussing Bjork's upcoming CD, Vespertine, her most melodic and intimate work yet.

"It's about creating paradise on your kitchen table," she says. "Or under it."

Sensual, celestial, Vespertine is, quite simply, a gorgeous work that very well may become the favorite Bjork CD among her fans. It's eons more modern than Joni Mitchell's Ladies of the Canyon, but the sentiment is the same: Life's simple pleasures and moments are interpreted through a sunny, yet nonetheless piercingly shrewd filter. Bjork paints a soundscape of domestic bliss that lifts off to euphoria only because she supplies each song with a firm foundation. The industrial clanking of her earlier work has been tempered to tender stroking: In "Cocoon," her vocals could brush the wisps of hair on a baby's forehead, they're so delicate, fragile, and loving. She sings: "Who would have know a beauty this immense/ Who would have known this saintly a trance/ Who would have known miraculous breath."

Subtle, careful and deliberate, "Hidden Place," the first single, begins with rhythmic dissonance, tracking a tender, layered propulsive progression that breaks open to an incredible aural vista. "We go to the hidden place," exults Bjork, creating it herself with eager and joyous shouts. She catches her breath; there's a purity to her astonished awareness. In "Pagan Poetry," she focuses that intensity into a raw declaration of love: "I love him," she declares, over and over with an urgency that sounds near-painful. Then she composes herself, and the listener along with her: "This time I'm going to keep it to myself."

"Doctors cure diseases and shoemakers make shoes. It's my job to go through emotions and describe them to other people."

She's been in the public eye since the age of 11, when as a musical prodigy, she cut her first album in Iceland. Along the way, as her career has evolved, her love life made headlines, most notably when she teamed up with hardcore rapper Goldie in London. Having lived through that era when paparazzi swarmed outside her door (they still follow her around when she's in London), she prefers to keep private the current object of her affection. "In my position, it's my to be emotional," she says. "Doctors cure diseases and shoemakers make shoes. It's my job to go through emotions and describe them to other people. But the bad thing is that every emotion I experience is public property. It's good in a lot of ways, and in music, it's great, but with love affairs, it becomes really tricky, because the nature of love affairs is very private."

There are two levels working simultaneously in Bjork's career: the musical and the visual. With videos and still photographs, she plays with her image like an artist. Musically, she takes the pop rock form respectfully and ironically, as a means of communicating ideas that can be extremely esoteric, blending the antiquarian and new technology into a mix that is challenging, yet ultimately enjoyable. Who can forget the startling image of Bjork on her 1993 Debut CD, where she stood, looking like an androgynous alien, a techno Michael Jackson with tears in her eyes? Those combined elements -- stylized, technological, futuristic, and sweet emotional intensity -- have been her points of reference ever since. She's the ultimate translator.

"I've got a 10-year education in classical music, so early on everything was pushing me into becoming a composer. All the while I was concerned with being very much working-class," she says. "My whole family is very much for the people. My dad used to be an electrician, but he became a union leader, because he's a fighter. I definitely believe in artists' music, or eccentric music, that's the music I will listen to. But the music I will do for myself, always, will be the sort of music you can play for your grandmother or a 4-year-old, and they will get it. That's how I was brought up. Like you can be as abstract as fuck, but if your grandmother will get it, that's OK."

Contradiction is the crux of Bjork's art, as is synthesis (cue her song "Violently Happy"). Think about it: in pop culture, everyone but Bjork has a doppelgänger. Whitney has Mariah, Britney has Christina. As her career unfolds, Bjork looks much more to be Georgia O'Keefe than Janet Jackson. She's a dreamer and a realist, of the mind and of the gut, soft, sensual and steely, a futurist and an archivist, as tough a swaggerer as Ani DiFranco, as smooth and smart as Miles Davis. Bjork focusing on domestic bliss is almost a perversely sweet thing for her to do.

Following her success as a lead singer for the alterna-pop band The Sugarcubes, she went wild with industrial sounds and club beats on Debut . Dive-bombing through the air on the back of a bug in the video for "Human Behavior," she seemed the perfect new pop culture toy. Once she had her audience in her thrall, Bjork started serving up the heavier stuff. Her dance and pop hit "Big Time Sensuality," a joyous, manic romp, was accompanied by a black-and-white video that pushed the song in an unexpectedly somber direction: There was something engagingly disturbing about the sight of Bjork in a long silk dress, her hair in braids, dancing koo-koo on the back of a flatbed truck tooling around New York. And that was just the beginning.

"So, let's talk about my album. [Dancer in The Dark] was so depressing."

Bjork word her avant-garde edge on her sleeve for the follow-up CD, Post, driving a tank in the video for "Army Of Me," then sending up the musical in "It's Oh So Quiet," the Spike Jonze-directed video which had her front-and-center of a production number set in an automotive shop. She got bullish on Homogenic, styled by Alexander McQueen on the CD sleeve looking like the ruler of a death star, then morphed into an eerie silver bear on the video for the single "The Hunter". She went through emotional hell playing a near-blind factory worker who escapes into musical daydreams in Dancer In The Dark, and dug deep to create the accompanying Selmasongs. Now, with all her powers shining brighter and sharper than ever, she's constructed a tribute to beauty on an epic scale. Artists don't seem to have half the struggle in expressing anger that they do happiness. As she once sang in "Big Time Sensuality," "It takes courage to enjoy it." On Vespertine, Bjork deftly avoids any sticky sentimental potholes and employs the precision of a scientist and the ballsiness of a seasoned performance artist in realizing her vision. "Unthinkable surprises about to happen," she chortles with childlike glee on "It's Not Up To You."

After the gloom of Dance In The Dark, it sounds like she's rediscovering just how great it is to be Bjork again. That, combined with the goodwill that's been sent her way from fans of the film has Bjork enjoying a feel-good vibe long after the Cannes Film Festival, where she won the best actress prize. Anne Heche at the Golden Globes was farklempt upon meeting Bjork, as was Winona Ryder introducing her at the Oscars. Bjork, of course, sang her nominated song "I've Seen It All." She lost to Bob Dylan, which was inevitable, but nonetheless a pity: Her song was the most original, and dammit, her performance swept Julia's Erin under the red carpet.

"The last year has been outrageous," notes Bjork. "I've spent most of my time since the film came out in New York. People stop me quite a lot on the streets. In a very sweet way. It feels very genuine. I was actually taking the piss out of it with my friends, saying t's just amazing that people are so verbal in this city, on the street -- 'I love your shoes!' They really let you know how they feel."

What she said in the past still holds true: Bjork reaffirms that Dancer In The Dark was her first and last film. I ask her if that's still the case, and she says, "Yeah, for sure. I knew when I was a kid that I wanted to do one film, and it would be a musical. So, this was the one. A lot of people think that because of this film, I don't want to act again because it was so painful, and that is not the case."

(Suddenly a jazzy vocal of "My Favorite Things" plays on the stereo system in the cafe. This song featured prominently in Dancer In The Dark. I call it to Bjork's attention, and ask her if she thinks the waiter put it on because she's in the restaurant. "It's a coincidence," she says. "A good one, yeah?"

"I guess because I sort of became a little bit famous, I believe in individuality and dressing a certain way."

Somewhere in the back of her mind, she says, she knew how difficult acting in Dancer was going to be. The director, Lars Von Trier, would stop her and tell her that she didn't have to push herself so hard. "I would say, 'Listen, this is the only way I can do it, so get off my back.' I actually went deeper in many cases than he wanted me to. So I think I knew from the outset how hard it was going to be, but that doesn't mean that I didn't get upset about how fucking painful it was at times. I did. But then again, I dealt with it." The big crying scene at the end, she says, wasn't the most painful for her. "It was actually a release of pressure. So, let's talk about my album. The film was so depressing," she says, in a Julie Andrews moment.

There's another venue that Bjork is something of a messenger for, and that's fashion. Over the years Bjork has worn designers whose clothes are as avant-garde as her music, but she's never jumped on the fashion-press bandwagon. Dressing for her is another creative collaboration. She's very catch-me-if-you-can about fashion, and in the past has admitted to being irritated about being followed or copied. What she's wearing today is beautiful, but she won't say who made it. "I'm not sure," she says, "It's probably inside." She obviously can't take the dress off to examine the label, so that's that. I don't take this personally, especially after watching the Oscars and noting Bjork steadfastly declining to say who made her famous swan dress. ("A friend," she told all the style press, although later in the papers that friend was revealed as Marjan Pejoksi.)

Now she explains her position on fashion and the media. Basically, she feels that talking about style takes all the fun out of it. "I like fashion when it's a creative thing, and it's about expression. When it's about waking up in the morning and feeling a certain way, and putting clothes on that will support you as an individual. I guess what I don't like about fashion is when people turn it into sort of a power or control thing, where it's about how much money you have, showing off your position or class. Million of people care told that if they don't wear something, they can't get love and they'll be lonely. And also, I guess because I sort of became a little bit famous, I believe in individuality and dressing a certain way. All this copying stuff, I'm really against it. A lot of people have picked from the designers I've worn. But there's not one designer whose entire body of work I like. It's sort of a Monty Python joke: 'You're all individuals.'"

"I had several eggs under my dress. I kept trying to drop them, but bodyguards kept passing them back to me."

Her swan dress at the Oscars prompted a stream of commentary. Those who knew Bjork got it and loved it. Those who have been trained to see celebrities in uniform Armani didn't get it. Bjork explains why she wore what she wore: "It was a tribute to Hollywood, the musicals, Busby Berkeley, that sort of thing." The dress came with some original accessories -- eggs-- which no doubt freaked out the style press. Photos showed her standing next to an egg, a wiggy Marilyn Monroe from The Seven Year Itch. "That was just for the red carpet. I had several eggs under my dress. I kept trying to drop them, but bodyguards kept passing them back to me. That was quite funny: 'Hey man, dropped something?'"

Even out of costume, Bjork is a theatrical presence. Her speaking voice, much like her vocals, has a pugilistic swagger and a child's seeking to be heard. As Bjork speaks, her hands are alive, shaping her words, running through her hair, at one point stretching each side of her face like a kabuki ask. Every once in a while, she'll end a statement with a wide beaming isn't-that-lovely kind of smile. Sometimes she gets a faraway look and her voice quavers. And yet her convictions are steely.

Bjork says she wrote most of the songs on Vespertine during the year of filming Dancer In The Dark, in locations as far-flung as Denmark and Spain. Having explored painful emotions for so long, Bjork was ready to offer up some sweetness and a light. Not that she was naive about the direction she was heading in. Not at all.

"In the past, I have been very anti-escapism," she says. "I thought people were being cowards by making pop music the didn't sound like their own life. I'd listen to the radio and say, 'That's not like my life. What's she's singing about? I've never felt that, you know?' I tried to make songs that actually sounded like everyday life." And for Bjork, who grew up with hippie parents, scorning music that let the sun shine in was all part of her rebellion. "I was very occupied with reality, and thinking that people didn't like their lives. That they were cold. I was very much into everything that was real and stark, and cut the bullshit. I guess Homogenic was very much like that. The beats were distorted, I was singing confrontationally. Definitely, the film was like that too. I guess, after getting that out of my system, the place where you find yourself at is a place where you whisper, sort of quietly ecstatic and euphoric. You can create a little bubble, and inside the bubble, everything is perfect. That's proof of the human spirit conquering mundane, dull situations. Sort of killing boredom. So I was very much up for that, and almost in taking the piss out of it, too. Like having choir boys singing at the end of one song: 'ah ah ah,'" she says, offering a little aria that comes on the heels of "Pagan Poetry."

"In the past, I have been very anti-escapism ... I tried to make songs that actually sounded like everyday life."

Because she's singing about creating a personal paradise, it's natural to want to know a bit more about Bjork's own. Does her kitchen look like the colorful little room featured in "Venus As A Boy" video? Yes, she says, and adds that many of her household items are in that video. "I guess I'm really organized," she says. "But naturally so. A lot of people don't know that about me, because it's very hidden; I guess that comes from being brought up with a lot of hippies, when being organized was almost a fault. So I would hide that very carefully, and sneak off with my rucksack, and get out of town and concentrate on school. But ti would be really hidden. Yeah," she says, smiling. "So I think my flat is sort of messy, but I know where everything is, if that makes sense to you."

Musical instruments make her house a home, where she lives with her son Sindri by Sugarcubes guitarist Thor Eldon. Bjork has a pipe organ, a celeste, and a harpsichord at her place in London, and a celeste in Iceland. "And then obviously the laptop goes wherever I am." Bjork loves her G3; Most of the songs on Vespertine were written on it. "It looks pretty fucked, yeah. Some things are broken on it. You know the little lid on the back, with all the inputs? That's fallen off." Bjork downloaded several sound effects to create Vespertine's aural texture, including music box arrangements.

And then there's the non-technical aspect that's crucial to Bjork doing what she does best: walking. Bjork loves a good mediative stroll, plucking melodies from the ethers she takes her daily constitutional. "I've been walking outside in nature since I was a little child, singing a few hours every day. That's still what I have to do. It's as important for me as food or sleep." She smiles. "I've found a lot of good little routes here," Do you walk by yourself? "Yes. That's kind of how I wrote most of my melodies." Do you sing out loud? "Yeah. For sure. This is probably one if the few cities where you can without getting locked up." Do people recognize you when you're singing? "Yeah, but they don't give a shit. I mean in London, there's paparazzi following me around wherever i go. Here, people don't care. They're just like, 'So?'" So, New Yorkers have heard most of the songs on Vespertine, whether they know it or not. "Yeah, that's a nice thought. I guess I really believe in 12 notes on the piano. It's so magical. You kind of hit note two and you do note nine and note seven three times, and that's a map to a certain emotional location. And if you do note seven and then note two five times, that's a map to another emotional location. It's my favorite thing in the world: the power of melody. For centuries, folk melodies have had a very symbolic meaning to human beings. It's a map to our feelings that nothing else can map out. So I think I'll always be a melody kind of girl, you know?

"I've been walking outside in nature since I was a little child, singing a few hours every day. That's still what I have to do. It's as important for me as food or sleep."

Much of Vespertine, which takes its name from vespers, evening prayers, is inspired by chamber music. It's the kind of music, Bjork says, that ladies would play in drawing rooms for guests. "Now we have laptops," she continues. "Laptop beats. Harps and celestes, and music boxes, they download very well on the Internet. Acoustic instruments downloading on laptops; it's all about the communication between these two."

Vespertine was recorded in the same studio in Spain where Bjork recorded Homogenic. "I went there last Easter for three weeks. My son came, and his school friends, too." Speaking of whom, what, one wonders, does Bjork's 15-year-son listen to? Could she possibly be subjected to Britney Spears?

"He doesn't like that song," Bjork says, and I'm assuming that she's referring to "Oops… I Did It Again." "He likes Limp Bizkit, Eve."

If he liked Britney or Christina, would there be a problem?

"I don't think so," Bjork says. "I quite like that my friends have got different music tastes. I'm really curious about what makes other people tick, and it doesn't have to be the same things that make me tick, for sure."

What's on Bjork's current must-listen list? "Orchestral stuff, Matmos, Oval... 90-percent of the stuff I listen to is really obscure. Like, a guy who would make music with five insects and there's only five copies of that CD in the world. I think I will always be into melody, but very rarely will I listen to vocal stuff. I listen to quite a lot of abstract music around my house. Most of it is noises with no narrative. Electronic textures. But I think my rrrrole." she says, rolling those Rs, "is very much to be a narrator in abstract situations."

Bjork has a few theories about this multi-media mission she's on. During our conversation, she puts into perspective a few things about the visual aspect of her whorl.

"With a lot of videos, I never have a marketing plan like a lot of pop musicians do," she says, scarfing down the last of the Brie. "I let the work just take as long as it needs to, because the creative process is like a plant. That's the best thing about creativity. You can't say, OK, by Tuesday, I want this twig to have grown three centimeters northwest. It won't do that; it will just go whenever it wants to. The only thing you can do is make it feel good, and make sure you give it the nourishment it wants. I'm very protective of the creative process and go out of the way to protect the visual artists who work for me."

"90-percent of the stuff I listen to is really obscure. Like, a guy who would make music with five insects and there's only five copies of that CD in the world."

Two names surface in her explanation of this mission she's on: Carl Sagan and David Attenborough. "For most people, the eyes are a lot more developed than the ears," she says. "For most people, music is a pretty abstract thing. If you look at my songs as a cave, the words and the photographs are the guide who goes out of the cave and says, 'Listen, look in here.' Sort of a David Attenborough thing: If you look right here, there's a but of joy here, and if you look on the left, there's a bit of humor. Go a little deeper in the caves, and there's some pain. The words and the images are most like signposts, a tool to describe the dogs, because I want to communicate. I am obviously spoiled rotten, having such genius collaborators to work with."

Speaking of collaborations, Bjork significantly influenced pop culture in 1994, when she wrote the little cut for Madonna's Bedtime Stories CD, which, in retrospect, can be seen as the project that paved the way to her Ray of Light success. Dreamy, atmospheric, and throbbing, the tune placed Madonna in a cerebral dance context -- Bjork's terrain -- singing about her decision not to use words anymore, to dismiss language and give over entirely to feeling. I'd heard from a friend who interviewed Bjork a few years ago that she wrote the line "Let's get unconscious, honey," because those were the words she wanted to hear from Madonna.

I ask her if this is true, and Bjork responds: "I think at the time, yes. But that's like six years ago, when everything about her seemed very controlled. I think she's a very intuitive person, and definitely her survival instinct are incredible. They're like, outrageous. At the time, the words I thought she's say were, 'I'm not using words anymore, let's get unconscious honey. Fuck logic. Just to be intuitive. Be more free. Go with the flow.' Right now, she seems pretty much to be going with the flow.'"

This prompts me to ask Bjork is she thinks she might have put those mellowing-out thoughts into Madonna's head."Well, I wouldn't credit myself for that," she says. "Not at all. That's a question for you to ask her."

(I sent a fax to Madonna via her publicist Liz Rosenberg, with the question: "Did singing the lyrics Bjork wrote for Bedtime Story lead you in the direction of going more with the flow?"

A day or two later, I receive this e-mail from Liz Rosenberg: "I wish I could get an answer from Madonna for you. She's deep into rehearsals for her your, and I can't get any info from her for a while. I can tell you that Madonna certainly thinks Bjork is inspiring and a brilliant artist. Madonna is a huge fan of her music. I've never thought Madonna was a 'go with the flow' person before or after recording Bedtime Story. She goes with a flow -- but it's a flow of her own creation, if you know what I mean.")

"As a kid I always had this romantic idea of me in a lighthouse with a pipe organ, being a composer, and kind of doing it all myself."

When I ask Bjork her if she's surprised by how much she's accomplished so far, the answer is yes. To hear her talk about it, she's the Unlikely Pop Star. "In my head, as a kid I always had this romantic idea of me in a lighthouse with a pipe organ, being a composer, and kind of doing it all myself. I don't need any outside stimulus. Also, because I enjoyed being on my own so much, I never really understood the word loneliness. As far as I'm concerned, I was in an orgy with the sky and the ocean, and with nature. Now it's all about thousands of people, and I'm communicating with them full-on."

That she's been straddling the fine line between the commercial and the avant-garde for over a decade is a near miracle. Bjork says that a vague sense of dissatisfaction pushes her along: "I'm very hard on myself. The film was probably one of the biggest things for me to get over. Then again, with every album I walk away from there's always a moment where I think, 'Shit, I could have done that better.' And then the trick, of course, is to use that fuel to do another thing. Through the years you learn to use the disappointment as drive for the next project."

Later in the conversation, she expands on that thought: "I guess I have days where I think I'm pretty pleased with the amount of work I've done, and then there are days when I go, 'Fucking hell, I'm never going to get it together before I die. I've just got 50 years. Fucking hell. You lazy slag, you know. Sort it out.'"

"North America is like the moon, or China. It's very exotic."

Weeks later, Bjork is in front of the camera on a suburban New Jersey street for the NYLON photo shoot. The childhood home of the hairstylist is the location chosen by photographer Terry Richardson. The house itself is a paneled-den kind of place. Bjork dubs it "excellent," even though she's allergic to the Siamese cat. It feels a bit like something out of Moonstruck when the hairstylist's Italian mom makes everyone a huge lunch. Bjork tries the tiramisu, and then tries on clothes in an upstairs bedroom. She seems to be very much the perpetual outsider who fascinated the natives; they want to see her for a last quick chat, Bjork says she feels this too: "North America is like the moon, or China," she says. "It's very exotic. I definitely feel like a visitor here. And I really like it. It's like if you go to China or something, and you've been invited to a fireworks event... you just go for it." Later, as Bjork frolics in a neighbor's front yard across the street, laughing and cavorting for the camera, I can't help but think of whats he said earlier about being alone in Iceland, in an orgy of nature. "Hidden Place" pours forth erin the boom box she's brought, a giant silver Sony that looks like a dashboard. One song follows the next, casting a spell over the street. The music is as relevant here as it would be in the trendiest club. That's a tribute to the power of Bjork vision, and the strength of her melody. She may be far away from Iceland, but she's at one with the elements, even in New Jersey. -- JAMES SERVIN