Entertainment

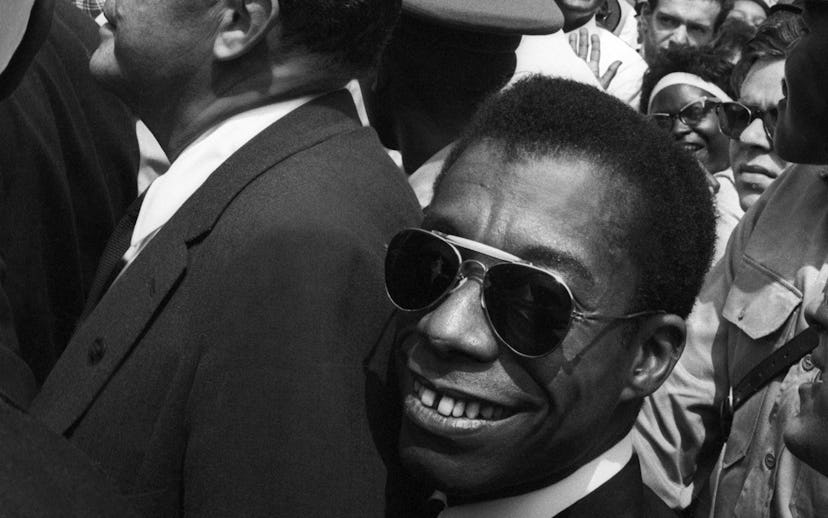

‘I Am Not Your Negro’ Gives James Baldwin A Voice

The film hits theaters tomorrow

The following feature appears in the February 2017 issue of NYLON.

James Baldwin’s essential texts defined an era of black American writing, but for veteran filmmaker Raoul Peck, it was a lesser-known work that led to the genesis of his latest documentary, I Am Not Your Negro. In his final years before a premature death from stomach cancer, Baldwin set about writing Remember This House, an exploration of the parallel lives of Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X—all three of whom were murdered by white men. This unfinished manuscript serves as the blueprint for Peck’s film, which stitches together evocative footage from the civil rights era, video of Baldwin’s own speeches, and stills from the late ‘50s to the present day.

In letting Baldwin’s text (as narrated by Samuel L. Jackson) do the talking, Peck highlights the power and eloquence of his language, as well as the enduring relevance of his critique. Baldwin’s discussion of media culture and its shaping of racial narratives is as insightful now as it was 50 years ago, but it is Peck’s choice to marry Baldwin’s words to contemporary images that makes for the most chilling viewing.

The juxtaposition of lines such as “You watch the corpses of your brothers and sisters pile up around you” with photos of Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, and other young black victims forces the viewer to confront how little has changed since the civil rights era. In the wake of an emboldened far right and an upswing in racially motivated hate crimes, it’s particularly skin-crawling to see shots of white people brandishing swastika-emblazoned flags and white-power placards that are disturbingly similar to current post-election news footage.

But beyond its searing institutional critique, the film is also a bittersweet document of historical black culture. Footage of 1960s Harlem shows a bustling hub filled with glamorous and beautiful characters, evocatively illustrating the hope and pride inherent in such lines as “When a dark face opens, the light seems to go everywhere,” while video of Dr. King and Malcolm X in conversation underscores the plurality of efforts to smash racist structures, despite their apparent conflicts.

Nonetheless, I Am Not Your Negro is not an easy film to watch, and should leave all but the most insensitive American viewers with feelings of immense fury and discomfort with the country in which they live. The magnificence of Baldwin’s language and astuteness of his arguments, however, make it a ride worth taking.