Entertainment

Why ‘Making a Murderer: Part Two’ Is Just As Important As Part One

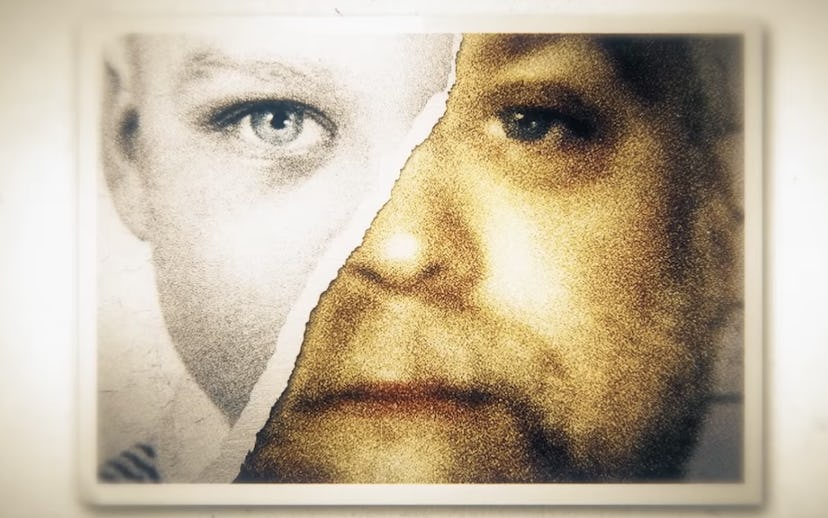

The series creators talk about revisiting Steven Avery’s case

In 2015, filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos released their Emmy Award-winning docuseries, Making a Murderer—unaware of the impact it would have on audiences. An instant sensation, the show focused on two men from Manitowoc, Wisconsin: Brendan Dassey and his uncle, Steven Avery. Avery had served 18 years for attempted murder before being exonerated and released, only to be charged and convicted along with his nephew for the murder of photographer Teresa Halbach two years later. The series explored the two men's conviction, and brought to light many unknown aspects of the case, and led many people to think Dassey and Avery had possibly been framed for the crime by local police.

Three years, countless paperwork, and a verifiable storm of news coverage later, and Ricciardi and Demos are ready to debut Making a Murderer: Part Two on Netflix. And while similar in style to the first part of the series, Part Two takes on an aspect of the fight that many would consider much less compelling: the post-conviction appeals process. Granted, in true Making a Murderer fashion, Ricciardi and Demos manage to make even the nitty-gritty procedural engaging—though they're quick to reiterate that their original motive was to make "a social justice film."

Just as Part One shined a light on America's trial system and the way justice is carried out, Part Two provides a pertinent look into what happens once the cameras turn off and the media circus dies down by following three new attorneys: Laura Nirider and Steve Drizin—Dassey's post-conviction legal team—as well as Kathleen Zellner, a big-shot Chicago lawyer now representing Avery.

Read our Q&A with Ricciardi and Demos, below, to find out more about what it was like returning to Manitowoc, their perceived impact on America's true crime obsession, and if Part Two is really the end of this story.

The easiest place to start is to ask you both why you felt the need to follow up on this particular story.Moira Demos: At some level, we knew the story wasn't over. It's real life, so things continue. And at the center of our story is Steven Avery, who, if nothing else, is a fighter, and he's right at the end of episode 10 of Part One saying, “I'm not gonna give up, I'm gonna keep on going.” So then the question for us was, “What would that look like?”

We knew we were entering this new phase of the process—the post-conviction phase—which is a much lesser known area of the law to most people. What we knew about it was it can be quite procedural but, more importantly, it can take a long, long time. So we had to find out what might be happening, and we had these two men, Steven and Brendan, who were in prison for life but were both proclaiming their innocence. And they’re challenging those convictions. But of course they need advocates, so it was about reaching out—or, reaching back out. Laura and I filmed Part One, and [then found] out if they would be interested in participating again. Then, we reached out to Steven's new attorney, Kathleen Zellner, introduced ourselves, and spoke with her about the possibility of filming—and about the kind of access that we would need because, as in Part One, we're all about the process, so we would need a certain amount of access to tell the story. Once we knew that both teams were on board—that Steven, Brendan, and the families were on board—it seemed like something worth pursuing, but we had no idea it would amount to 10 additional episodes. It was very organic.

Zellner is quite the character. What was it like working with her?Laura Ricciardi: She's an incredibly seasoned, winning attorney, so it was really fascinating. We were the beneficiaries of her and Steven's emphasis on transparency, actually. When she meets with a potential new client, she wants to know whether or not that person's innocent. To the best of her ability, she wants to feel confident that she's taking the case of someone who's been wrongly imprisoned, and that she's fighting for what she believes is right—which is to free someone who doesn't belong in prison. So, because of her threshold issue, she satisfied herself that Steven hadn't committed the crimes for which he was currently in prison. She and Steven were basically like, "You can have a window into our process, you can watch me at work with my forensic experts behind the scenes, work with my legal team, my investigators behind the scenes, because we have nothing to hide." So that was really an incredible opportunity for us as filmmakers to be a fly on the wall, to watch someone of her stature work.

Were you expecting reception to Part One to be the way it was? Why do you think it resonated with so many people?MD: We certainly could never have expected the level of the response, the scale of it, the scope of it, all of that. But that said, we were thrilled, because as creators, you're making the work to share it, and it’s quite a long process. It took us 10 years to make it and find a home for Part One. But that whole time, we had the viewers in mind, and we had them in mind when we were arcing out episodes, trying to give them an experience akin to the experience we had living through these events and documenting them. We had them in mind, too, when we were trying to sell the project and turning down two-hour time slots. Like, that would be us telling a story instead of us showing a story. So it was just thrilling to have the viewers respond in the way that they did.

We heard back from viewers about so many different aspects of the series that had touched them, whether it be comments about, "I grew up in a town like that,” or “in a family like that,” and “I've never seen that part of America represented on TV, it means so much to see something like my life shown.” Or whether it be people that work in the system and have never felt like, "I finally have people talking about the real issues that we struggle with, and what we're up against in the criminal justice system.” Then, of course, there are the people that are very interested in the evidence—being armchair detectives—and they have something to go on too. But, I mean, we believe that the underlying theme of the series is accountability, transparency, identity… This is what our world is struggling with. So I think having a story that really takes some time to dwell in that space is really what's behind that interest.

Did the public's perception to Part One affect the way that you approached the making of Part Two at all? LR: No. I mean, we thought it was important, in the so-called hook of [the first episode], of the pre-title sequence, to acknowledge the response to the series and everything that sort of mushroomed out of that, because we needed it. When we were back in Manitowoc filming, we were filming a changed world for our subject. It didn't change our process, but it changed the world we were documenting to a certain extent, and we thought that was important to include.

What it was like returning to Manitowoc?LR:In terms of a group of people being more open, we had a new opportunity to film with someone from Teresa's life… In Part One, our access to Teresa's family—the people who knew and loved her—was press conferences that her brother Mike was holding, because those were public and archival footage that we licensed through a local television station who had more intimate access to the Halbach family and the community that loved Teresa. This season, we were very fortunate in that one of Teresa's college friends agreed to sit down with us, gave a very thoughtful interview, and shared archival materials with us.

What does it feel like knowing that Making a Murdererhas been credited as a big factor in America's true crime fascination and perhaps, more importantly, that it sparked interest in false convictions and innocence projects?MD: It's interesting because, it may be hard to believe, but we always thought that we were making a social justice film. Wenever thought of it as true crime. I think part of that is because, when we read about Steven Avery in the New York Times, and read the headline, "Freed by DNA, Now Charged in New Crime," it was really Steven who we were choosing as somebody in a very unique situation—somebody who could really take us on a journey from one end of the criminal justice system to the other. So it wasn't as if we were on the hunt for a murder case or even thought about this as “documenting a murder case.” We had an opportunity to look back with 20/20 hindsight at 1985, and what had gone wrong. Then, to have that same man step into the same system 20 years later after the advances in DNA and legislative reforms, and sort of test the theory of “Has the system improved? How will the accused be treated after all of these advances? Are wrongful convictions really a thing of the past, which is what was being said in the early 2000s?”

Of course, there is this genre of true crime, which we view as a responsibility of ours. True crime has often been used as a place to examine some social issues around class and justice… [And when] you've got a high-stakes story with compelling characters, you've got sort of a built-in audience. But then it's what you give that audience. It’s your responsibility to try to elevate it to something more meaningful.

Do you see there being a part three? LR: We're open. As Moira said earlier, we weren't actively looking for a particular type of story when we came across Steven Avery, and I think that there's a lot to be said for just… We also refer to it as "filling the well." Trying to consume and read and be open, and we think this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity because the story presented so many key dramatic elements. But it's real life, and I think, in that way, it makes the story richer. But we certainly plan to keep on working in film and television, and we're looking at projects in the scripted spaceas well as in the nonfiction world.

Making a Murderer: Part Two premieres on Netflix October 19.