flashback friday: my cover with michelle

reread our 2007 interview with the actress!

ON A BLUSTERY AFTERNOON IN BOERUM HILL, BROOKLYN, MICHELLE WILLIAMS merrily pops wheelies with a stroller, inside which her one-year-old daughter Matilda screams “Ira! Ira!” and pumps her chubby fist. As we amble east on Atlantic Avenue, dodging vortices of dead leaves, the contradictions of the borough unfold. French bistros abut old Baptist churches spilling loose congregations dressed in their Sunday best; liquor stores and halfway houses face boutiques hawking Diptyque candles and hand-crocheted Japanese cashmere socks; long dishdasha tunics for sale swing loose in the wind, pushing plumes of incense skyward. As passersby coo and wave at the adorable green-eyed baby, few seem to notice the woman pushing her -despite her pale-blond waves, aviator sunglasses, gold chain, narrow black jeans, and stop-sign-red ballet slippers. But Williams is, secretly, noticing them. Studying their gaits, the way their hands hang. Formulating in her mind where they might be from, where they’re going. What they love, what they’ve lost. Who they want to become.

Some people become actors because they crave attention. Michelle Williams prefers, in art and in life, to disappear. “My family and I have become inextricably linked with Brooklyn in the media, but it’s kind of a little hideout for us,” says Williams, now nestled inside one of the aforementioned bistros, where a boisterous, mimosa-drunk brunch crowd of French expats is making it easy enough for her to go unnoticed. Over the course of our two-hour conversation, it becomes clear that Williams is as personally perceptive as she is professionally emotive. She asks as many questions as she answers -rare for any interview subject, much less a famous actor- and regards me, during the occasional silences, curiously yet gently, as if she might play me one day. She doesn’t understand why actor profiles always assess the subject’s skin and attire (though both are, in her case, unassailable); she engages in lively dialogue on such topics as the origin of skyscrapers (Williams is an active member of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, an organization opposed to Atlantic Yards, Frank Gehry’s massive high-rise development, planned to be built just a few blocks from her townhouse) and the connection between President Bush’s rhetoric and the media-fashion complex. All of which leads me to wonder: What happens when an introvert, an intellectual, a person so invigoratingly human, becomes a celebrity?

“One if the things that I battle with is feeling self-conscious, like people are looking at me, people are taking my picture, you know, somebody’s whispering,” she says. “So you feel like you want to protect yourself from criticism and from judgement. And you feel like one of the ways you can do that is to have an appearance that nobody can poke fun at. So you try and sort of build yourself up in these ways, and it can take you further away from who you are and further away from being in the world, and being in the world is what being an actor is all about: watching people and observing people.”

It’s been quite a ride for the 26-year-old actress. Within the span of two years, Williams -theretofore associated with WB soap Dawson’s Creek and regarded as a talented, quirky, but ultimately under-the-radar indie ingénue -landed in Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, fell in love with Heath Ledger, delivered their daughter, earned an Oscar nomination, and became, together with her fiancé, not just stalks of trash-tabloid paparazzi but unwitting mascots for New York’s outer-borough hipster diaspora. For a certain segment of young Brooklyn, already prone to navel-gazing in print and on blogs, the arrival of the hunky, insouciant Ledger and the stylish, mysterious Williams (who had actually already lived in Brooklyn, in Carroll Gardens and Red Hook, for several years) has been cause for celebration. Brooklyn was already cool, but Ledger and Williams, as Hollywood royalty, proved it to the rest of the world.

“It’s a funny word, cool,” says Williams, furrowing her brow and staring at her plate of spinach-and-goat-cheese crêpes. “It kind of scares me a little. It feels elusive and it feels like something that other people have and you don’t. It’s important to hang onto the idea that your style or your taste are not your values, and they’re not who you are, and they’re not what make you a good friend.” To Williams, values are paramount, and right now, hers revolve around being an active parent. “I always sort of imagined I would be a young mother,” she says. “Kids just bring such a natural order to your life. I used to have all these questions that felt like they would never be answered. I’d agonize myself with them. You know, ‘What am I going to do with my life? What am I going to do with my day, what will I do with my time? Who will I be with? Will I wind up alone? And having Matilda, I don’t plague myself anymore. I know what my life is like. For the next 18 years, I’m devoted to somebody’s welfare. It took all that noise out of my head… It wasn’t that long ago that I was sleeping until noon and not doing anything all day. Literally nothing. And now my life’s not going to be like that again. I think about it when I go out with my friends for a night and, you know, 10 or 11 o’clock rolls around, and I look around the table and think, ‘Wow, I’m the only person here who has a kid, I’m the only person who has to go home now to get up by six to function for the rest of the day.’” A pause. “Although I feel like maybe having kids young is going to come back in vogue.”

Williams, as it happens, has always been something of an early bloomer. Convinced -essentially since she could talk- that she was destined to act, she left her native small-town Montana, where she grew up the fourth of five siblings in a “not terribly closely knit” family, at the age of eight for San Diego, to be closer to auditions. By 15, she had financial emancipation from her parents, a high-school diploma, and her own place in L.A. What followed was, she says, “just a whole laundry list of embarrassing TV shows and commercials”: a guest appearance on Baywatch: Hawaii, a made-for-TV movie titled My Son is Innocent. “At that point I was so young and I hadn’t made the friends that I was going to know for the rest of my life and had just left my family,” she explains. “I didn’t have any values and I didn’t have any taste and I didn’t have any ideals. So I just kind of floated around from paycheck to paycheck without knowing what I was doing or why I was doing what I was doing.”

It was Dawson’s Creek -that seminal teen-angst drama beloved by millions- that raised Williams’s profile considerably, but she has also, in the eight years since Jen Lindley first made Dawson Leery’s lantern jaw drop, quietly amassed an array of smart, memorable performances that, examined as whole, prove her rise to the A-list to be less sudden than it might seem. Unbeknownst to many, she has a respectable stage oeuvre, having starred in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard at the Williamstown Theatre Festival (stomping grounds of the Paltrow family) and Mike Leigh’s Smelling a Rat on Broadway, among others. Her appearances in such indie standouts as 1998’s DIck (a campy gem in which she played a Nixon-obsessed teen alongside Kirsten Dunst), 2003’s The Station Agent (for which she was nominated, as part of the ensemble cast, for a Screen Actors Guild Award), and 2005’s criminally overlooked The Baxter (as a geeky secretary) have been consistently captivating, and Williams even wrote a screenplay with two friends -“about three girls living in a brothel, which makes me sad when I think about it now, that that’s where I felt like I belonged or something” - which was sold to a production company but never made.

“I guess they tend to be the more interesting people,” says Williams of her choices in parts. “It frustrates me -oh my god, I’m opening up a can of worms- it’s frustrating to be a woman. I didn’t want to trade on my sexuality as a woman because it seemed easy and not really the point. Also, some of it was just my fault. I didn’t have a lot of confident feelings about myself, so I wasn’t really capable of playing somebody who did.”

While such self-doubt may sound startling coming from the mouth of, as it were, a babe, Williams has, one quickly realizes, always worked from within her mind rather than her body: After all, it was a palpable, inward-facing discomfort, not her beauty, that made her role as Alma in Brokeback Mountain so heartrending.

Still, from the moment Williams stepped onto the red carpet in a saffron-colored gown and Veronica Lake waves at the Academy Awards this past March, she appeared destined for superstardom, and her schedule for the next year is packed accordingly. Within the next few months or so, she will appear in The Hawk is Dying, opposite Paul Giamatti, as a “woman who’s going beyond fear and going beyond beauty and breaking herself down. I have no eyebrows, the ugliest clothes you can possibly dream of, and this insane gray mop of hair”; Ethan Hawke’s semi-autobiographical The Hottest State; and Todd Haynes’s eagerly anticipated Bob Dylan biopic I’m Not There. In 2007, she’ll also star with Phillip Seymour Hoffman in a new Charlie Kaufman (Adaptation) project, Synecdoche, and lend her voice to Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are (yes, even her animated roles are flawlessly chosen). At the moment, she’s filming The Tourist, in which she plays an enigmatic, streetwise sex-club worker opposite Ewan McGregor and Hugh Jackman. “I’ve never played anybody overtly confident and sexual,” she says. “I’ve interpreted that as being vain, and little by little I realized, hmm, I’ve never done that before because it frightened me I wouldn’t be able to. So playing something like this that could seem more straightforward is oddly more of a challenge for me than a lot of other things. But it’s really lively, really sharp, smart dialogue that I love that just happens to be from somebody who’s very sexy and sexual.”

As Williams assesses her characters and the places she’s filmed, it occurs to me that she approaches her work and surroundings with the sensitivity to gesture and motivation of a novelist; it’s hardly surprising, then, to discover that books are, aside from acting, her favorite pastime. In fact, Williams says, “I loved books so much that it was kind of consuming, or isolating, I guess. I feel like now that I’m a mom I’m more in the world and less in my head. I just had walls in my apartment made of books, which was physical and metaphorical. It’s nice to go through a bit of a cleansing process. But I do miss them, and I miss having a story constantly in my head.” Williams’s current favorite authors include Mary Gaitskill, and Haruki Murakami -“Mmmm, I looove After the Quake. I remember each of those stories so vividly, it’s like I was there” - and she’s currently mulling over a chance to play Charlotte Brontë, though when asked about it, she responds as only a true bookworm would: “There is hardly a person on earth that I would rather play; I just don’t know if it should be done. Some people are so dear and loom so large in people’s imaginations and hearts that maybe it’s just better left alone. I don’t know, I’d like to maybe just play her in my living room or something.”

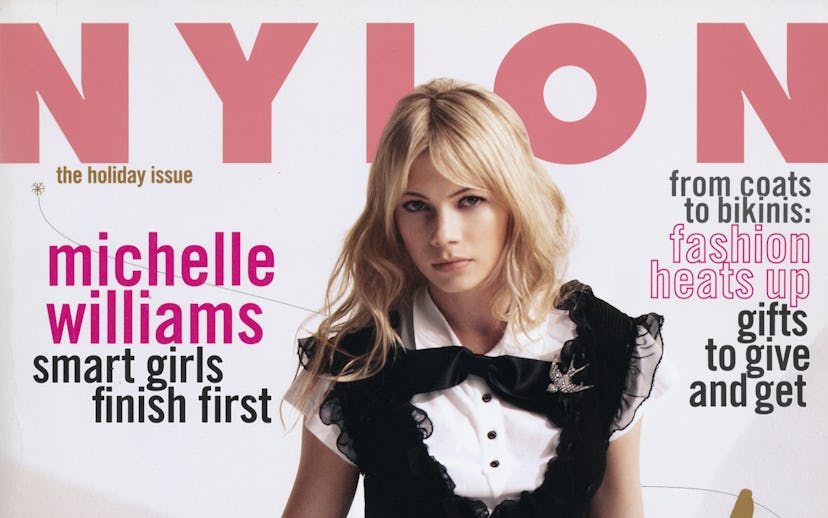

Williams’ proclivity toward narrative extended event to the NYLON shoot, which she conceived with the stylist and photographer as the story of a woman slowly coming undone - her way of making interesting what she normally considers “the bane of my existence.” “It’s such a weird thing to want to be an actor and to really love acting and then to kind of be obligated to be a fashion model,” she says. “With photos, I like when it’s a creative process and not just about taking -you know how when you were a kid and they had this thing at the mall, what was it called? Glamour Shots -I feel like that’s what most magazines really want. I feel the pressure to be beautiful, which makes me ugly. Sometimes I just resent that you’re supposed to be pretty to be a woman or an actress. I don’t feel like that. And that’s OK in movies and that’s why I love them, because they’re about the complexity and diversity of the human race, whereas magazine pictures are all beautiful.”

As self-protective as she may be, when the moment is right, the shyness peels away, and Williams, line by line and frame by frame, reveals herself to be one of the most talented and promising actors of her generation. “When I’m working, something in me stops and dies,” she says. “That internal monitor that tells you, ‘Oh, that thing you said was stupid, or that face that you’re doing now is weird.’ It turns off and when things are working right it’s this really blissful, forgetful time when I don’t really know where I’m going and I don’t know where I’ve been. I’m not myself, and I stop judging myself for just a minute. I don’t know why it happens, but it’s this intense, blissful ride.” -- EVIANA HARTMAN