Entertainment

Rebecca Harrington On Social Media In The Workplace And Creating Viral Content

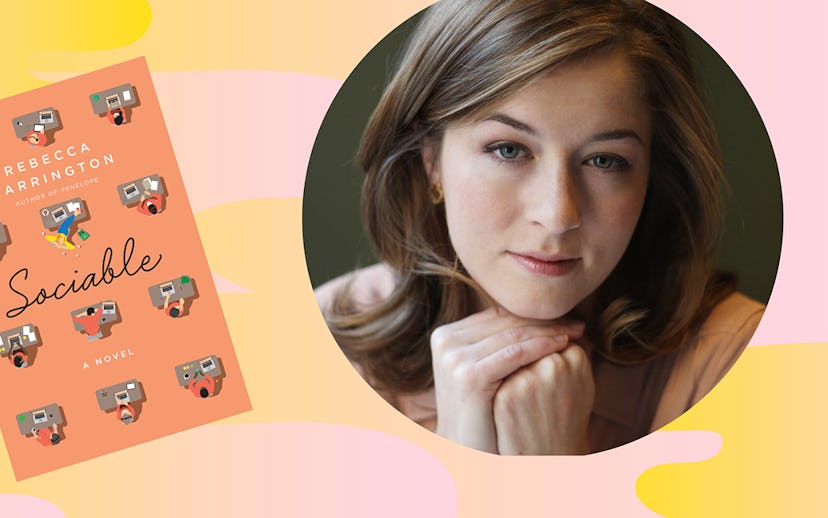

Her new book ‘Sociable’ is out now

Plenty of the situations in Rebecca Harrington’s new novel, Sociable, feel like deja vu moments from that awkward post-college/early 20s phase we all had. As was the case for so many of us, Sociable’s protagonist, Elinor Tomlinson, has that classic New York City dream: work for a highly touted publication, live in a sweet apartment, and inspire #CoupleGoals envy on social media. Instead, Elinor finds that her life involves being an underpaid nanny, sleeping on a foam pad in a cramped walk-up, and discovering that life with her college boyfriend isn’t exactly going according to plan.

Things start to change for Elinor once she lands a job at Journalism.ly, an online outlet with one goal in mind: creating viral content. To her surprise, Elinor is really good at this. Illuminated against a hilarious and satirical backdrop, Harrington writes about navigating digital media in the workplace, handling a bad breakup (through equally worse online dating), and what feminist friendships look like after college.

Below, we talk with Harrington about her book, social media’s effects on our careers, and what it even means to make “viral content.”

You’re not a big social media user. What made you want to write a book, then, about this topic?

I always thought it was a kind of fascinating thing that was really hard to tackle in fiction, just in the sense that [with social media] you have the ability now to sort of write about yourself in the third person. You have this ability to craft and narrate your life, and you also have the ability to look at other people crafting and narrating their own lives.

Obviously, looking at other people and the conventions of social media actually affects—in an interesting way—the way you narrate your own life. One of the things that I thought was interesting about the conversations surrounding social media is that you have a lot of people talking about how bad it is to kind of cultivate your own life, but you don’t really hear a lot of people talking about what it's like to watch other people curate their own lives, and then become very influenced by that. There are all these conventions of social media; there’s a tone, there’s a language, and I was really interested in the idea of how those conventions and clichés really change the way you think about yourself. Do you process your emotions differently because there’s a way to process them and a way to think about them?

What went into your research process for Sociable?

I was first scanning all of these social media networks over and over again, and I was shocked at how many people kind of sound the same. There’s just a way to discuss yourself, and it’s sort of sincere, but somewhat funny [and] somewhat engaged, and I was basically trying to capture the tone of that in the way Elinor thinks about herself. I was constantly scanning everybody’s Instagram and Twitter.

Elinor struggles with that plight most recent grads face: You have this idea of where you want to be, like a writer at Harper’s, but it doesn’t quite match up with your reality.

I think she really is trying to resolve the tension, but, also, does she even really want to be a writer at Harper’s? Because that’s sort of [her boyfriend] Mike’s dream, [whereas] she’s really good at coming up with viral content. It’s this interesting thing where I think she wants the respect the institution could confer on her in a particular way, but then she ends up working at this content farm instead.

At Journalism.ly, we're presented with two different schools of thought when it comes to media: There's Elinor's and then J.W's, her boss who has a traditional print background. Why offer these two diametrically opposed ways of being?

Journalism, historically, was this incredibly hierarchical thing, but then in the past 10 years or less has completely changed. There is something interesting about somebody who has a completely different, more traditional background interfacing with these kids and really having to be kind of deferential to them—even though it makes [J.W.] want to die—because it is sort of topsy-turvy, in a way.

As was the case with the protagonist of your first book, Penelope, Elinor is a woman who lacks this sense of social awareness, and it’s funny but frustrating at the same time. How does she represent that “millennial in the social media age” mindset?

I think what’s hard about being a millennial, in a way, is that she goes through this breakup, and it’s really hard and it kind of sucks, but she almost doesn’t know how to resolve the tension between how the world wants her to think about what happened to her and how she thinks about what happened to her. So there’s a huge difference between her individual thoughts and how she filters those thoughts between what everybody else is thinking about breakups [which is], Breakups are hard, but, at the same time, they teach you how to grow. She’s not really there. She doesn’t really feel that, but she wants to feel it so bad. In some ways, I don’t think she ever resolves it.

For many people, that would be when you really lean on your friends, and you handle Elinor and her best friend Sheila’s friendship in an interesting way. They have this idea of being “good feminists,” and yet both women are so self-absorbed. How do you see that reflected in second-wave feminism today?

There is this dialogue, but then there’s also this tremendous tension; it’s almost less painful and less personal to talk about feminism in a way where you sort of accept the idea of feminism, and then it’s incredibly hard to live feminism in your own life. I do think sometimes, because there are all these social conventions of not being “judgmental,” in some ways, [Elinor] felt unable to weigh in on Sheila’s life, and Sheila felt unable to weigh in on [Elinor’s] life, and the way they resolved this is they were both like, “You go, girl! That’s amazing,” even though they were both making shitty choices. But that was supposed to be the substitute for closeness. It’s kind of dark.

There’s a great, very true-to-real-life moment when Elinor sends out a tweet to promote her Journalism.ly piece: “Just want to let you guys know, I wrote something incredibly personal.” I just loved that because you see that all the time on media Twitter.

You do! What I thought was so interesting is, in a way, that is sincere, right? She is saying [that], but, at the same time, it’s also fake because that’s what everyone says all the time about everything. There’s always this weird tension between what you’re actually doing and how much you’re shoehorning what you’re doing into the conventions that people are establishing about how to do those things.

There’s this idea at Journalism.ly about giving opening up to the public. We’ve seen this personal essay boom, especially with online outlets, but how personal is too personal on the internet these days? Is there even a line anymore?

I actually don’t think anyone’s personal at all. I think the cliché has calcified the genre to such an extent that I feel like every time I read a personal essay, they all have the same sort of specific beats no matter what they’re about. So, in some ways, I think people are personal online, and, in some ways, I think they’ve never been more guarded.

Why do you think our society is so obsessed with consuming this type of viral content, though?

At least now, everything is sort of tailored to Facebook [and] is very personalized. I think people really like content that tells them about themselves in a way.

I love the fact that a person like Elinor is writing things to help people figure out their lives when she has no idea what she’s doing in hers.

Yeah [laughs]. I worked at the Huffington Post, so I saw what went viral all the time, and it was also kind of a fantasy of mine because I was terrible at making viral content. But I always wished to be good, so she’s kind of living my dream here.

How do you think you would have reacted if something of yours went viral?

I would have loved it! It would have been awesome. But I was always doing these horrible articles, and it was facts about presidents or “Who’s the hottest president?” Which I thought was going to go viral, and [it] didn’t. I was shocked [laughs].

Who is the hottest president?

Rutherford B. Hayes! That was cool, but only I discovered it.

Sociable is available for purchase here.