The other day, a video of typical internet ridiculousness was dropped into our Slack room. It showed a young boy dressed as a wizard, rapping about being the black Harry Potter. It went viral, partially because of its creativity and likely its ability to entertain. But its virality also probably—definitely—had to do with its trap music leanings.

Trap music is a subgenre that evolved from Southern hip-hop roots, with "trap" referring to a place where drugs are sold. But lately, the label’s become attached to any music with a fairly upbeat tempo and, preferably, a song to which you can fervently twerk; it’s turn-up music at its best. Everyone from pop stars to EDM DJs has co-opted the music style, leaving the definition of what does and doesn’t qualify as trap muddled.

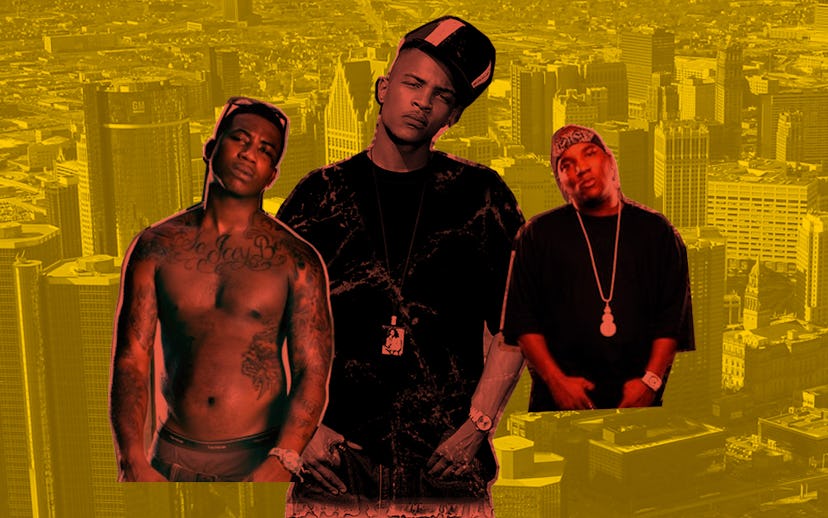

The founding father of the genre is a topic discussed at length on many corners of the internet. Ask one rap fan, and they might tell you Jeezy or Gucci Mane were the originators, ask another, and they might tell you T.I. was. Ask T.I., and he’ll also tell you T.I.: “I would just go as a historian and point out facts. Before my album Trap Muzik was released in 2003, the term was never even heard," he tells us. "There was no such thing as trap music, or the genre being defined as trap music.”

He’s not wrong. Up until the early ‘00s, trap wasn’t considered in a musical capacity until T.I. came along. He put the name on the map, though he wasn’t the first person to use the term in a song. In 1998, on Outkast’s “SpottieOttieDopaliscious” track, Big Boi raps, "United Parcel Service and the people at the post office didn’t call you back because you had cloudy piss/ So now you back in the trap, just that, trapped/ Go on and marinate on that for a minute." The duo was the first to introduce the concept of the trap as an actual location, but also as a state of mind.

Of course, rappers were talking about the trap lifestyle decades before the term was coined. “Nas was making trap music. What you think he was rapping about? He was rapping about the streets, he was rapping about the trap. Jay Z is, like, the rap god and what was he rapping about? The streets, the trap,” rapper Young Dolph tells us. “It was a different day, different year, different generation. Back in the day, it was just the streets, but they was talking trap back then.” Different name, same underlying struggle.

Like many other trap artists of the early ‘00s, T.I. used trap music to reflect his situation, painting a story of the times. He says:

The thing that's so special and important about artists like us is that we come from nothing. These environments that we speak of are just atrocious… and what we had to rise up of is unspeakable. So for us to take something that's so gruesome... we took the crack epidemic basically, and the war on drugs, and a system that was set up for us to fail, and we made something out of it that was positive and that we could actually use to our advantage rather than falling victim to it. Those experiences, those accounts, those details of our childhood, we applied and used it for our music. Whether it was introspective or whether it's celebratory, it seeds and fuels the music that we put out.

The trap itself kept him down, but trap music helped him out. And it motivated others to do the same.

;

“We used to have the Martin Luther Kings and Malcolm Xs and the different people who led the black communities, now I think the people who could take their places are the rappers,” Dolph says. “Who brings thousands of people together in venues nowadays? Artists. Those are the ones who hold the biggest influence.” Dolph, himself a trap artist, realizes that and he tries to use his influence to motivate. In the same song that he talks about the trap lifestyle, he makes sure to also talk about morals and taking care of your family. “My music comes with a message: get your paper, stay out of the way, and live your life. That’s it,” he says.

Today, though, trap music has become less about the lyrics or the message behind them and more about the beats. T.I. might’ve put trap on everyone’s radar, but producers like Lex Luger, Zaytoven, and, most recently, Metro Boomin fine-tuned its sound. Zaytoven once said in an interview that, for him, the trap is whatever you’re doing to make money—be it cutting hair or selling drugs—the music of the trap is the soundtrack to the hustle.

What does that soundtrack sound like? Mostly loud drums, snares, 808s, hi-hats, kicks, and lots of bass. The production mash-ups vary, but the cadence is unmistakable. “If it's got a hi-hat and the beat is slow, it's like 70 beats per minute, it's a trap beat,” rapper Juicy J tells us.“It could be on reggae, it could be a pop record, it could be a country record, it's got a snare in it like that, and a kick drum, it's a trap.”

Trap music is undeniably intoxicating and, as Juicy J notes, with time, everyone wanted in on the phenomenon. As we’ve seen with rock 'n' roll before it, once artists catch a whiff of a good thing in music, it’s bound to be appropriated and turned into a watered-down version of what once was. Now, what’s considered trap is just as much Migos’ “Bad and Boujee” as it is Major Lazer’s “Lean On” or even Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse.” The style of trap more or less remains, while the lifestyle has been left behind.

Cry tears of Columbusing if you want—they would be justified—but artists like T.I. and Juicy J aren’t mad at the genre’s shift. “I think it's all a part of the evolution,” T.I. says. “It's transcended to a different genre that is more indicative of the sound than of an environment… It's not like the trap music as we know it is standing still and not being progressive, it's just advancing along. I think as long as both versions, or both renditions, are advancing and progressing and maintaining a consistent pace of evolution, I think that it's still a strong genre however you look at it.”

Juicy J’s simply happy to see something that originated in the hood gain mainstream popularity; it’s flattering if anything. "I never pictured that kind of sound being on commercials and movies and stuff like that. Everybody used to call that kind of sound the underground. People used to tell us that ‘your music will never go nationwide, it will always stay underground.’ And it's good to hear all of these songs now,” he says. “You've got your pop trap, you've got your street trap, you've got your EDM trap, they even got rock trap… It's still the same bounce but it's kind of, it's different. It sounds different."

It’s a beautiful thing for a genre of music typically designated for a particular subset to permeate other cultures and gain national notoriety—especially if those at its helm encourage it. But when those same artists start to become erased during the evolution, it becomes a problem. Google “trap music artists” right now, and the first five people that pop up all come from an EDM background (or some version of it), all are DJs, and all are white. T.I. doesn’t even break the top 10, and an actual rapper, Waka Flocka Flame, doesn’t pop up until the sixth position.

While I was writing this very story, news broke that Georgia Tech now offers a course titled “Exploring the Lyrics of Outkast and Trap Music to Explore Politics of Social Justice” to its students. So, there may be hope for us yet. T.I. also lists Young Thug, Migos, RaRa, and Future as artists who are helping to preserve the genre’s roots. Don’t get us wrong, we have Diplo tracks on the same playlist that we have Jeezy ones. It's hard to dismiss the infectious electronic spinoffs it's birthed, but it’s all fun and games until someone dubs Taylor Swift a trap music expert.