Entertainment

What Is The Most Truthful Onscreen Version of Washington, D.C.?

Sorry, but ’24’ is trash

There are certain things that we learn about from film and television because if we are lucky or privileged, we never have to experience them firsthand. Things like the criminal justice system, the entertainment industry, human autopsies, espionage, or alien invasions. But the last few years have brought us a vast buffet of shows and movies about the one place that seems to combine all of the above: Washington, D.C.

Americans, unsurprisingly, have developed a great appetite for shows purporting to explain just what the hell is going on in this town. But when approaching a buffet, strategy is key. My purpose here is to provide you, the reader, with a means of sorting the bacon-wrapped scallops from the moldy egg rolls, so to speak, and in so doing answer, now and forever, the question that has bedeviled viewers across America: Which version can we trust? Is The West Wing really just escapist hoo-ha? Is House of Cards a true portrait of the city’s underbelly?

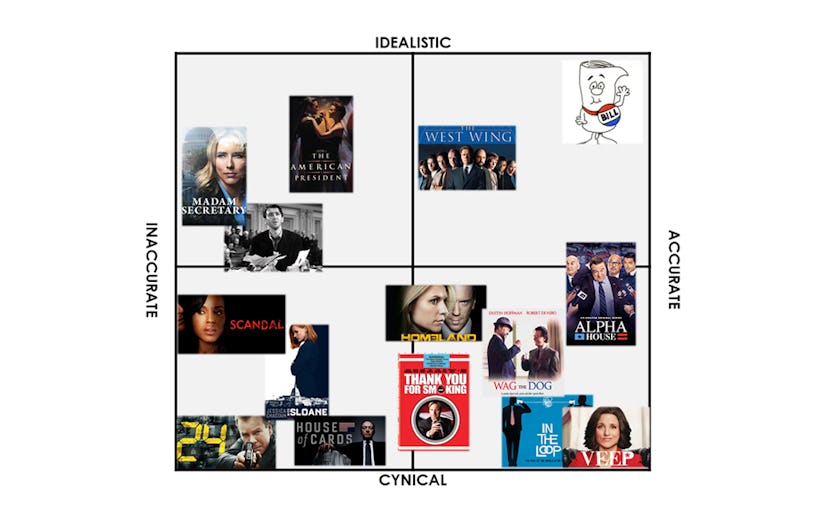

Therefore, as a public service, I present this ranking of the 15 most relevant TV shows and movies. I’ve graded them on two simple criteria: accuracy and attitude. Accuracy—that is, a title’s faithfulness to the protocols of governing—is not enough; it must also capture the spirit of the people who actually do that governing.

A note: In limiting this particular buffet to 15 titles, I deliberately excluded any movies based directly on real events (e.g. All the President’s Men, Game Change, Recount, Casino Jack, Lincoln, 13 Days, Charlie Wilson’s War, and one particular unsung masterpiece: Oliver Stone’s W.). These movies are works of history—and pretty good ones at that—but not imagination. They focus on particular moments in time, not official Washington as a whole—as an organism. I’ve also left off shows that never earned a significant audience, like 1600 Penn (a bad 2012 sitcom about the president’s zany family), The First Family (a bad 2012 sitcom about the “second black president’s” zany family), and Commander in Chief (a 2006 drama with Geena Davis as the president, which in one episode so badly misrepresented the D.C. suburb of Hyattsville, Maryland, that ABC had to formally apologize to the town), because come on, no one saw them.

Also, there’s one show that merits honoris causa recognition as the only title that understood that the real D.C. is a predominantly black city with more citizens, and less representation, than the state of Montana. 227 was an Emmy-winning sitcom from 1985 to 1990, about the lives of a set of black women living in a group home in Northeast D.C., and it owned. I haven’t put it on the matrix because it doesn’t actually engage with politics, but until Netflix or someone adapts Edward P. Jones’ Lost in the City, it deserves some love as the only show that has ever deemed the stories of the people who actually live here worth the telling (except, for some unfathomable reason, Wedding Crashers).

And now, to the judgment.

THE INACCURATE

#15: 24 (2001-2010, 2014, 2017)

Weighing in at 100 percent cynical and 100 percent inaccurate, 24 was actually shot mostly in California, but it’s included here for the extent to which it shaped American thinking about national security during the Bush years. Jack Bauer et al. willingly and happily served as Bush Administration’s most potent defense of the Patriot Act, prisoner torture, mass surveillance, permanent war, and, in the case of Dick Cheney, shooting people in the face. Despite being in active contact with the White House, the showrunners dismissed considerations as petty as intelligence-sharing, the chain of command, or the U.S. Constitution. The sniveling surrender monkeys (or, as we would say today, cucks) who did complain about such trivial things were shortly revealed to be terrorists or cowards or both. 24 based its entire moral universe on the “ticking time bomb” myth, which is the same logic used by the people who say, “Why don’t they just make the whole plane out of the black box?” or, more recently, “Why don’t we just build a wall?”

24’s legacy is so toxic that it has caused the subsequent D.C.-based Kiefer Sutherland vehicle, Designated Survivor, to be stricken from this list, but I have it on good authority that that show is trash, too.

#14: Scandal (2012-2017)

Has President Fitz ever signed a single piece of legislation?

#13: Miss Sloane (2016)

Early on in this joyless farrago about lobbyists in D.C., a senator played by John Lithgow is interrogating Jessica Chastain, who is playing an idiot’s idea of an ambitious woman (benzo-popping, escort-renting, no-life-having), and he says, “What troubles me is the amount of… influence you have. We’ve seen communication from senior figures in Washington who feared that you, a lobbyist, could destroy their careers with a snap of your fingers.” He goes on to imply that she is “steering the ship of American politics.” Not only is that a stupid sentence, it’s also rather unlikely that a senator leading an open hearing would suggest that a lobbyist could boss the Senate around.

Miss Sloane presents an entirely cartoonish vision of both professional woman and K Street (also, what’s with the “Miss?”). While it does feature a few thimblefuls of lobbyist tradecraft, it is otherwise soaked in cliché, basically a grim pedantic Aaron Sorkin rip-off without the wit, hopefulness, empathy, or command of the English language. You didn’t see it, but if you had, you would have been treated to this dialogue:

JESSICA CHASTAIN (addressing her new lobbying team): A senator’s priority isn’t representing the people, it’s keeping his ass in office.

ASTONISHED DO-GOODER LOBBYIST WHO DRESSES LIKE SHE WORKS AT BUZZFEED: That is so cynical!

JC (all in one breath): Cynical is a word used by Pollyannas to denote an absence of the naivete they so keenly exhibit.

Chastain deserves an Oscar merely for making it from one end of that sentence to the other.

#12: House of Cards (2013- )

House of Cards purports to “realism” harder than any show since The West Wing. Legislation is discussed! Gavels are struck! Secretaries and undersecretaries are shot in stark desaturated lighting! Journalists are dogged (and occasionally fuck their sources, which is as common in shows about D.C. as green-eyed characters in bad fiction)! And so at first, official D.C. watched this show addictively: It was a combination of Richard III, Macbeth, and our AP Government textbooks. But after the first season, it became clear that the show’s method of handling the characters who got in Frank and Claire’s way was simply to kill them, and we lost interest because as much as people here might like to shove their opponents in front of a subway, Metro trains only run like every 30 minutes at night. By Season 2, the show had become one more bad cynical opera about power.

Yet it survives—or it did, right up until we all discovered last week that Kevin Spacey was a whole lot more like Frank Underwood than anyone wanted to believe—because it relied on the two things that Americans fundamentally believe about Washington, D.C.: One, that everyone here is corrupt by nature; and two, that it’s all going perfectly according to plan. We believe these things together because we are more afraid of chaos than we are of corruption. Frank and Claire Underwood were appealing to us because we desperately want them to exist—we want to believe that it is possible to control the U.S. Government. The UNDERWOOD 2016 stickers slapped on bumpers across America last year were not entirely ironic.

House of Cards wasn’t just cynical about government—it was cynical about Americans. In this it appealed to our worst instincts. On the other hand it did give us Mahershala Ali. For D.C. residents, though, one lie was more cruelly deceitful than all the others: there is no cheap and authentic BBQ shack like Freddy’s in this city, and if there were, it would be under perpetual siege by Yelp-following D.C. food nerds.

#11: Madam Secretary (2014-)

As interesting as it is for one show to try to honestly portray the work-life balance of a highly successful woman (Tea Leoni plays the Secretary of State and mother of three), which is a major issue for families in D.C., ultimately this conspiracy-obsessed show is about as faithful to the business of diplomacy and the State Department as its network mate CSI: Miami is to actual forensic science. It’s still more accurate than House of Cards, though. Extra points for pronouncing the UN General Assembly correctly as “UNGA.”

#10: The American President (1995)

To the extent that this rom-com, about a widowed president (Michael Douglas) who strikes up a love affair with an environmental lobbyist (Annette Bening), exists in cultural memory at all, it does so as Aaron Sorkin’s dry run for The West Wing. It features lavish idealism, Aaron Copland-esque score, and roles for Anna Deavere Smith, Joshua Malina, and, most importantly, Martin Sheen. Today, though, the movie feels smeared with Vaseline. It approaches the difficulty of governance gamely, establishing a political foil in Richard Dreyfuss, but its climax is a single rousing speech from the president in which, through sheer force of folksy rhetoric, he reverses his own policy, knocks Dreyfuss on his political ass, gets the girl, and reminds America of its true potential.

This movie relies on our fundamental belief that one speech, just one true speech, can change minds. But that isn’t how it works, not even in 1995. Obama’s “Amazing Grace” speech was a moment of greater spontaneity, vulnerability, and leadership than anything Sorkin could write. And what did it do? Mostly it just made us cry.

#9: Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Frank Capra and Jimmy Stewart gave America its most enduring expression of idealism in the face of corruption and machine politics—and a model for every single campaign for Congress, city council, and school board ever since. Its great lie is that innocence wins over experience and power. And yet, while we now dismiss it as saccharine, it should not be ignored that for most of Mr. Smith, everything about Washington conspires to tear poor naïve Jimmy Stewart to pieces.

When I first started compiling this graph, I parked Mr. Smith all the way in the upper left, dreamily idealistic. That’s how I remembered it. But the more I started looking back into it, the more it began to creep eastbound and down. The Hays Office initially objected to “the generally unflattering portrayal of our system of government.” They weren’t wrong. Mr. Smith is fueled by cynicism in the way that Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life is fueled by suicidal depression. Smith arrives in D.C. completely star-spangled with optimism, only to find this town is the Mos Eisley Spaceport of America, a wretched hive of shark-like journalists and jaded fast-talking secretaries (in this, it is entirely correct). Soon political goons are kicking the shit out of a bunch of literal Boy Scouts. In the end, Stewart saves himself through an act of physical self-destruction and moral heroism, implying that nothing short of nearly killing oneself on the Senate floor can actually enact change. The only mind which is truly changed is Claude Rains’, who is so racked with guilt that he attempts to shoot himself. And what does Smith get for his pains? A boys’ camp.

A note on the condemned: Strangely, all these inaccurate shows are inaccurate in exactly the same way: They subscribe to the Great Person theory. The Most Powerful Lobbyist in Washington. The Top Fixer. The Only Man Who Can Stop the Terrorists. The Man Who Can Bend Congress to His Will. The One Who Will Stand Up For the Little Guy.

To understand Washington, understand that these people do not exist. Because there is never just one of them. There’s no Neo, there’s no Dumbledore, there’s no Lorax. Every single congressional candidate promises to “shake things up in Washington,” and then when they arrive, they discover, like a man in a Yakoff Smirnoff joke, that Washington is the thing that shakes you.

Presidential candidates on both sides are the most egregious examples of this: Would-be presidents market themselves as monarchs because we want to believe that they will be as immediately effective as monarchs are. The only candidate in recent memory who did not do this, who instead ran on a platform of working with Congress and federal agencies to enact data-driven incremental policy shifts with the best chance of ensuring broadly shared economic and social growth, lost to the guy who promised to make everyone say, “Merry Christmas” again.

But this is exactly why this administration has been such an unprecedented failure. Governance, at its most basic, entails persuading other powerful people to use their power to help you. Because the truth is that there is no such thing as “the most powerful person in D.C.” Washington is a city of countless power centers, of competing fiefs that form alliances and rivalries and who defend their turf. It’s nearly feudal. This is the only way to understand it—and it’s the way that all of the shows on the angels’ side of the X-axis present it.

THE ACCURATE

#8: Thank You for Smoking (2005)

Nobody in D.C. will be surprised to discover that all but one of the titles in the Accurate/Cynical quartile are satires. Thank You for Smoking is a Bush-era briar patch of a movie about Aaron Eckhart’s crack tobacco lobbyist who, rather than having a Sorkin-esque come-to-Jesus moment, genuinely believes in the importance of what he does—not in the value of cigarettes per se, but in the personal freedom he believes they represent. In this, he is a far more truthful depiction of most lobbyists than the gothic caricature of Miss Sloane. His foil is William H. Macy’s absurd, vindictive liberal Vermont senator named, wonderfully, Orville K. Finisterre. That this movie merrily lampoons liberals is natural, since it’s based on a book by Christopher Buckley, son of the old crypto-nazi himself, William F. But the fact that a few years after this movie came out, Christopher switched parties in response to the GOP’s embrace of characters like Sarah Palin, means that the D.C. it depicts is sadly a little bit dated. Also, it loses a bunch of points for leaning on the female-reporter-sleeps-with-source-to-get-a-story cliché.

#7: Homeland (2011-present)

As it enters its seventh season, this show is getting to be the Grey’s Anatomy of putatively-realistic NatSec shows. Unfortunately, its case officers are about as true-to-life as Grey’s doctors are. As a friend at the Agency pointed out indignantly, the characters on Homeland blithely wave their cell phones around in SCIFs. SCIFS are Special Compartmentalized Information Facilities—secure rooms where top-secret intel is discussed, where the whole point is that electronics must be left outdoors; that’s what makes them secure.

That said, whatever you think of its politics, Homeland does do an admirable job of depicting the emotional toll that intel work can take on individuals, who live not only with constant paranoia but with constant confirmations of that paranoia (which is the paranoiac’s dream and nightmare all at once). Its portrayal of the fighting between bureaucrats and intel officers is admirable, but it’s still a very limited snapshot of D.C. itself. Gets extra points for its depiction of Mandy Patinkin’s marriage to a pragmatic, compassionate UN official, and for Mandy Patinkin generally.

#6: Wag the Dog (1997)

When Wag the Dog was released, it was a piece of madcap satirical absurdism in which a president commits an indiscretion with a young girl, and the entire apparatus of the White House communications team swings into action to create an entirely fake war with a random country (Albania) to distract the nation. One month later it was journalism: The Lewinsky scandal hit, and in response, Bill Clinton chucked some missiles into a random country (Sudan).

Twenty years on, it’s still relevant for the astonishing accuracy with which it prefigured the “fake news” phenomenon. Though “prefigured” may be the wrong word—fake news is a tradition as old as American journalism itself (look at what Jefferson and Hamilton did to each other). The only real difference today is that news comes at us from so many more vectors than it ever did before—so many that it takes real effort to parse truth from horseshit.

Were it not for its ending, in which Dustin Hoffman’s movie producer wants to take credit (the movie couldn’t help itself from satirizing Hollywood, too) and (spoiler!) Robert De Niro’s spin doctor reluctantly has to have him killed, Wag the Dog would be breathing down Veep’s neck.

#5: In the Loop (2009)

Apparently, when Armando Iannucci was making this movie (about British and American political maneuvering in the lead-up to a war, manifestly based on the invasion of Iraq), he didn’t know what the State Department looked like inside. So he walked into the building, flashed a basic photo ID, and said, “Hi, BBC, here for the 12:30,” and spent the rest of the day happily walking around the building, taking pictures and notes.

The whole movie’s like that—deadly accurate, transgressive, and ferocious with cynicism. Two lines, in particular, stand out, though. First, as the British delegation is heading to a meeting with the Americans, an aide says, “You know, they’re all kids in Washington, like Bugsy Malone but with real guns.” This is completely true—for all the greyheads in positions of power, there are dozens of Red Bull-chugging young aides, still bent double under student loans, who do all of the actual work. D.C. is a young city.

The other line is an immortal. A minister says, “It’ll be easy peasy lemon squeezy.” “No it won’t,” says his aide. “It will be difficult difficult lemon difficult.” No better description of the difference between campaign rhetoric and actual governing has ever been written. Just look at Obamacare repeal.

It’s easy to think of this movie—based on Iannucci’s perfect British show, The Thick of It—as a dress rehearsal for Veep, like the American President to The West Wing. And yet, there is a case to be made, especially now, with all the simian chest-beating the White House is doing toward North Korea, that it’s just as necessary. James Gandolfini’s war-weary general is alarmingly close to James Mattis, and David Rasche’s hawkish Assistant Secretary is all the Boltons and Flynns and Sebastians Gorka. And for all its savage, operatic humor, In the Loop’s ending is the most haunting, searing depiction of how wars actually begin since Dr. Strangelove.

#4: The West Wing (1999-2003, 2005-06, because Season 5 doesn’t count)

Outside of no-reservation restaurants and gay kickball, nothing is more fashionable in D.C. than hating on The West Wing. To invoke it with any kind of earnestness at all is to invite derision tinged with pity, and liberal use of the phrase “sweet summer child.” In this town, it is canon that The West Wing is pure liberal escapism. And it’s true: When it came out, Wednesday nights at 9pm with Josiah Bartlett, Nobel Prize-winner and TV Dad of Dads, were a warm, comforting refuge from the reckless stupidity of George W. Bush (which we seem collectively to have forgotten because somehow someone worse came along).

But what we of this city cannot admit, none of us, is that we hate on The West Wing because we so desperately want it to be real, and we will never get over the fact that it is not.

The truth is that it is impossible to understand Washington without accepting that buried and caged and shackled deep within every bureaucrat, politician, reporter, and aide's hardened heart, The West Wing still abides, glowing faintly but unkillably. A tiny, dogged ember of hope that somehow powers everything we do. Yet we cannot speak of it, because we have jobs to do.

But even those who don’t work here, who are simply looking for hope, cannot trust The West Wing. Not because it’s “not really like that”—in fact, no show has so scrupulously hewed to the protocols and regulations that govern the government. Nor because it teaches us, falsely, that idealism wins. In truth, the quixotic characters on The West Wing rarely succeed entirely. CJ’s efforts to stop the administration from selling arms to the violently misogynistic Middle Eastern country of Not Saudi Arabia end in heartbreaking failure, Josh and Toby’s dreams of making college cheaper are wiped out by an intransigent GOP, Bartlet and Leo engineer the illegal assassination of a foreign diplomat, on and on. The show acknowledged how hard, how frustrating governing was. More than any other title on this list, it understood how powerless even the president can be.

No, the reason we can’t trust it is because while the battle nerds on The West Wing are often willing to compromise on policy, they are never willing to compromise on their integrity. And that’s the most insidious lie that this show tells. Because integrity in this city is a commodity, like everything else. It’s a valuable one, yes—but that value means it can, and inevitably will, be traded. That’s the thing that Sorkin never allows his characters to do, but that’s the price of governing. Anything that can be traded, will be.

And yet, we keep that stubborn little ember alive, because some days it’s all we have.

#3: Veep (2012-Present)

Veep is shot as a documentary because it is one. It did not set out to be. The showrunners and actors have spoken out about their frustrations at the increasing speed with which reality keeps catching up to their satire, rather like how staphylococcus keeps overcoming whatever new antibiotic humanity throws at it.

Veep earns a rating of 100 percent accurate and 100 percent cynical because no show better portrays the sheer panic that engulfs people in the political world—the constant backstabbing among the underlings, the utter venality of Vice President and then, fleetingly, President Julia Louis-Dreyfus (boy, I like the sound of that), and, most of all, the way that the characters balance their hunger for power with their fear of getting caught. That’s one more reason that House of Cards is BS: Frank and Claire are almost never afraid of anything. But this is a town full of knives, and so it’s a town full of shit-scared people. And it should be. That’s the point of democracy: No one’s untouchable—look at Mitch McConnell’s polling numbers.

The difference between Veep and In the Loop is that the characters on Veep are spectacularly bad at their jobs. They bungle everything, they are laughably clumsy with the machinery of government, and they have all the leadership of a windsock. This may sound familiar. The best way I’ve found to understand the current administration is that it thinks it is playing Game of Thrones (Steve Bannon, in particular, is the High Septon). It thinks it’s engaged in an epochal clash, a great war against “the establishment” in which you win or you die; in reality, it is Veep in every particular.

That’s why today if you ask anyone in D.C. which is the most accurate show, they will say Veep. Yet it is not the most truthful, and that’s what we’re going for here. Veep’s problem is that if this city were actually like that, if everyone in it really was so spineless, sociopathic, and broken inside, the city would collapse in a matter of days. The miracle of D.C. is that even in the face of the sustained assault the past year has brought, it has held. Because Veep has no room for idealism—sincerity and earnestness are anathema to it—it conceals the one thing that makes this city endure.

#2: Schoolhouse Rock, “I’m Just a Bill”

Way darker than you remember.

And #1…

If there is one single golden key to understanding how Washington works, it is the fact that Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg were best friends. Not, like, collegial—they adored each other. They vacationed together, went to the opera together, rode elephants together. And the only show that truly inhabited the way this town can breed such an impossible friendship, that reconciled the vaingloriousness of politicians and aides with the fundamental optimism that makes this place go, was a little-watched two-season Amazon comedy starring John Goodman called Alpha House.

Created by Garry Trudeau of Doonesbury, who knows D.C. as well as anyone ever has, Alpha House was a brilliant conceit: Four Republican senators living in a group home (this was based on Chuck Schumer and Dick Durbin’s old setup). This group included Louis, the wealthy Nevadan closet case who owned the building; Robert, the one black Republican senator; Andy Guzman, who was very obviously Marco Rubio; and Goodman as Gil John Biggs, the former coach of the UNC basketball team whose ladder-climbing wife shoved him into politics. The cast also featured Wanda Sykes and Cynthia Nixon as their battle-hardened Democratic senator neighbors, who came over for drinks after work.

This acknowledgment of partisan amity, if not always comity, established Alpha House as more interested in getting at the ticking heart of D.C. than any other show. It understood that in Washington, you never burn your bridges because you know you’ll need them again someday. But beyond that, it understood a core truth about politicians here—often they feel, strangely, deeply out of place. As if this whole city were just a vast humid office, and their commute home was a three-hour commercial flight. Some politicians, of course, haven’t lived in their home state in years. But for many, both politicians and appointees alike, this place is practically King’s Landing, and they’re in wildly over their heads.

And maybe, ultimately, that’s why no one watched—because it asked liberals to empathize with GOP senators (even absurd ones), and because it asked conservatives to laugh at themselves. Because it didn’t treat the people who live here like wizard nerds or power-hungry sociopaths or gladiators, it treated them like people. America didn’t want to hear it. But it should have.

We shouldn’t just trust Alpha House because it’s a happy medium, combining the bumbling and cowardice of Veep (the series opens with roommate Bill Murray getting arrested and sobbing, "Why motherfucker, why?!" as he brushes his teeth) with the procedural realism of The West Wing and the hive-of-scum-and-villainy feel of Mr. Smith. We should trust it because it’s the only show with any fondness for D.C. and the strange and ridiculous way that life is lived here. It gets that, like Tyrion Lannister, people stay in this city because in some deranged way we like it, and we believe (here is where that tiny ember of West Wing comes in) that we can make it better. It even acknowledges, quietly, that there is a city outside Capitol Hill and Georgetown. But most of all, it presents us with a Washington where it is entirely possible for Antonin Scalia and the Notorious RBG to have gone to war during the day and to the opera together at night, and in these times, that, more than anything, is the Washington this city needs to remember it can be.