Entertainment

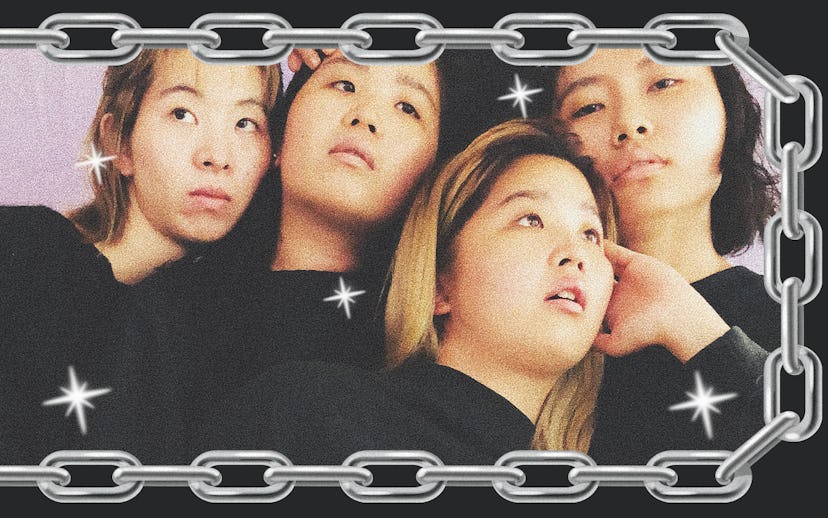

CHAI Is The Japanese Pop-Rock Outfit Turning Kawaii On Its Head

An interview with the quartet to discuss NEO-Kawaii and their music ahead of their tour with Whitney

It all goes downhill midway through CHAI's music video for "CHOOSE GO!" The four members are in the middle of an intense game of American football — well, as intense as it can get on a set. Kana, the band's guitarist, throws the ball to vocalist Mana, also her twin sister. Mana gears up to catch. Instead of a ball, however, in her hands lands a doll — one of those blonde-haired, blue-eyed plastic beauties that cry haplessly when you put them down — and a switch flips.

The game of football changes into sack-racing. Mana coos to the doll as if soothing her after a round of feeding. Their games now involve judging who is best at slicing bread in one stroke. All of this is set to the frenetic chant: "Change bad feelings." You eventually begin to wonder whether the "bad feelings" might be referring to the girls taking joy in football and partaking in something unbecoming of women.

Like most women, the members of Japan's post-punk quartet known as CHAI learned very early on the supposed code of conduct for being female. For them, it boiled down to the concept of Kawaii—the term used for anything cute or adorable in their native Japan. Outside of the country, Kawaii has become a marker of Japan's prolific entertainment industry and a staple in its commercial sector, where stores and shops are often dominated by adorable, bite-sized mascots that aim to attract customers with their innocuous looks. Beyond the realm of capitalism, though, Kawaii has also inspired a restrictive social template that women in Japan are often expected to adhere to.

"Kawaii is the best compliment [for a woman] in Japan. Usually, that means long legs, small waist, skinny, pale skin, small face, big eyes. That is typically Kawaii," explains bassist Yuuki, as the band — Yuuki, drummer Yuna and sisters Kana and Mana — congregates around a computer for a Skype call on a Sunday morning. Getting ready to fly to their next tour stop with Whitney, the girls are dressed in matching outfits, makeup-free, and much too chipper for this time of morning.

"Those [Kawaii] people are on TV or more like celebrities in Japan," Yuuki continues. "It's very specific what kind of people or looks is Kawaii. Other than that, everybody [who does not fit in] is not Kawaii."

By the age of 10, the members of CHAI had realized that they fell in the latter category, and reconciling with that fact took a toll on them. "We grew up with a complex because we were not in that category," Mana explains. "But at the time we didn't know how to change."

Although Kawaii as a concept first appeared in Japanese pop-culture as a handwriting trend in the '70s and expanded with the advent of Hello Kitty, the following decade was when the phenomenon fully saturated mainstream media, eventually serving as the template for how women should behave. "If you look at '80s Japanese idol music, fans expected the women who were idols to act a specific way," says Japan-based writer and critic Patrick St. Michel, who's been covering the country's music scene for a decade. "That really defined how a lot of people saw the concept of Kawaii or even being a young woman in Japan. Very innocent, demure — whatever words you can think of to describe Seiko Matsuda."

Pop idol Seiko Matsuda all but became the unofficial trademark of Kawaii culture in Japan for the better part of the '80s. Her immense popularity — between 1983 and 1988, all of her 23 singles hit No. 1 on the Japanese charts — only amplified the perception of Kawaii. Her quasi-childishness was the primary marker of her appeal: she often appeared on TV clad in pastel-hued children's clothes and sporting adorable blushes and giggles, prototyping the juvenile innocence, vulnerability, and carefree attitude that's a staple in Kawaii.

"That just became the idea of how a woman should behave in Japan in many people's minds, especially the media," continues St. Michel. "It goes from something kids were doing on their own to almost a brand. 'You can be Kawaii if you wear these clothes and act this way! You're submissive to the men in your life.' It really does end up being this thing that can force women in Japan into these roles that aren't fair, which CHAI definitely pushes against."

The band has termed their resistance as NEO-Kawaii. The bedrock of their oeuvre, it's a world where the only criterion for being cute is being you. Far from the reach of the "lipsticks, treatment, highlight cheek, eye-shadow" — as goes their song "I'm Me" — NEO-Kawaii is CHAI's quasi-camp realm where you don't hide your weight, put butter on your steaks, and always feel pretty. Your complexes are your charm; they are what make you cute.

"Everyone has a different complex, but they all have these insecurities," Mana says. "Once we started the band, we realized that maybe this was not only us, that there were a bunch of people feeling like us. That was the point. We wanted to spread the word— you can be who you are, even if you are not in that category. You are okay. You are beautiful."

These insecurities are a universal thing. It's not only in Japan.

To the members, the visual language of this message is of the utmost importance. One would think the path to resistance is seldom paved with pink satin and flowers, but this clash between ideology and presentation is what singles NEO-Kawaii out from other acts pushing against traditional cute culture.

"The basic [idea] is the same as people who play with punk and rock: wanting something to change," says Yuuki on why the band so heavily incorporates commonplace Kawaii elements in their videos. "However, people who are not Kawaii already have a complex, which is already negative. We wanted to change the negative into the positive."

Diving into a CHAI song is, in turn, a multifaceted lesson in dismantling social systems. The traditional Kawaii elements are ever-present — endearing juvenescence, babydoll dresses, and vibrant colors, most prominently pink — but this time, they've been stripped to their bare essentials and reconstructed with a more inclusive perspective. CHAI has weaponized its native elements to become more accepting of shortcomings.

This repositioning extends into their sound, where love-letters to gyozas, body hair and catchy English phrases — a residue from the early commercialization of Kawaii — blend in with their voraciousness to never quite stick to a genre. They alternate between frenetic post-punk and sweet, slow funk, pop, and traces of R&B. Collectively, they've named this melting pot of sounds CHAI. "We want to pick the best of them and create a new way," Mana says. "A CHAI way."

It's this progressive take on classic Kawaii that makes CHAI's music so delightfully unique, explains St. Michel: "I remember it was PINK [their first album], which has so many references to being a woman who has a complex about how small her breasts are, or just being slightly chubby.

"Another thing they do a lot which is interesting is that they sing a lot about food, something women aren't really expected to do unless it's like a cute dessert or something," he adds. "Their songs are about gyoza and deep-fried things, which is not something that is traditionally Kawaii. The things you like can be Kawaii even if they're not—even a deep-fried piece of meat can be Kawaii. They try to present it that way without sacrificing who they are in the process."

While CHAI's largely independent status has assured them a greater level of creative freedom, the rise in their popularity presents newer challenges. Outside of Japan, press has been quick to catch on to, and embrace, the group's new philosophy, but back home the nuances of NEO-Kawaii are often lost on interviewers.

"We are musicians. A lot of times interviews [with Japanese press] had nothing to do about that," Yuna says. "They know that we are sending a positive message, but sometimes people don't care about that. We have a problem with that."

"They probably didn't mean to be negative, but it did not sound positive," Kana adds. "Sometimes people think: 'Oh, those four ugly girls try to be cute.' We don't feel like the media is attacking us, but sometimes they misinterpret the words we use."

At the end of the day, though, media opinion affects very little of what they do: it's the fans that matter most. Yuna recalls one instance in which a fan came up and told them that their music inspired her to get over her insecurities about wearing skirts. Another told them that their music had helped her fall in love with the color pink again. As far as the members are concerned, this is the beating heart of NEO-Kawaii's ethos: to help people — no matter where they are from — get in touch with who they really are, imperfections included.

"We started to spread this message from Japan, but we never thought about it as being only for here," says Kana. "These insecurities are a universal thing. It's not only in Japan."