Entertainment

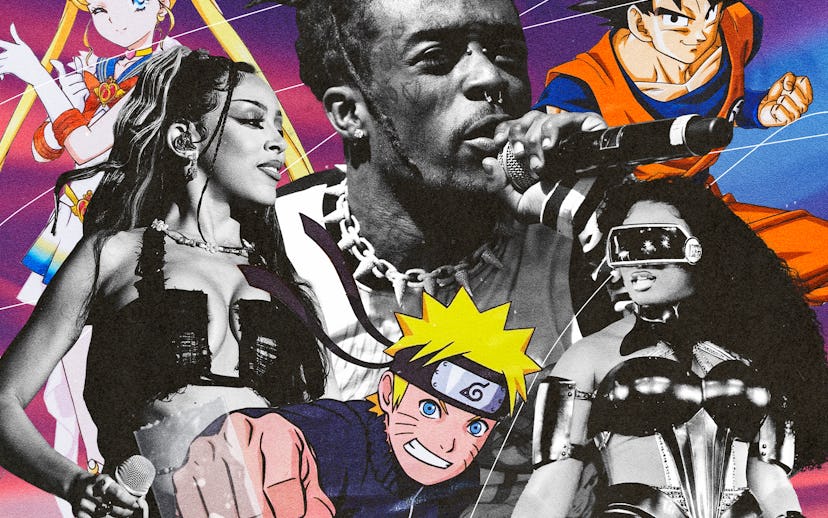

How Anime Is Inspiring A Generation Of Rap & Hip Hop

Anime references in rap songs by artists like Kanye West and Megan Thee Stallion are increasingly common — and historians say there’s a good reason for it.

Whether you love it or hate it, anime has firmly lodged itself within our cultural zeitgeist. Beyond being the inspiration for much of Western animation’s own action sequences (à la Avatar: The Last Airbender, Transformers, and Scooby Doo), more obvious anime references are popping up in mainstream media on a regular basis. Major celebrities like Michael B. Jordan, Megan Fox, Keanu Reeves, and Ariana Grande have all declared their love for anime in some form or another, but there’s a specific category of fans that I’ve started noticing recently: rappers.

Megan Thee Stallion has made Naruto references in her song “Girls In The Hood,” and Doja Cat’s “Like That” music video draws heavily on the transformation sequences in Sailor Moon (and we haven’t even started talking about her e-girl aesthetic). But it’s not just them: According to a quick Google search, Kanye West, Snoop Dogg, RZA, Pharrell, and Lil Uzi Vert have all revealed themselves as anime fans, watching classics like Akira, Cowboy BeBop, One Piece, Naruto, and Dragon Ball Z. But for someone who grew up mocked for watching anime, I was very surprised to see how boldly our culture’s most popular icons have shown their love of anime. A part of my love for anime stems from my desire for representation as an Asian American. To me, anime was a cartoon that existed in a world that centered around Asian culture. It was, in a way, one of the earliest forms of representation on screen that I felt like I could sort of resonate with. So why was anime resonating with rapers, and how were they finding it?

The answer was a lot simpler than I realized. “The 1990s saw a transnational boom in the global circulation and popularity of anime,” says William H. Bridges IV, an associate professor of Japanese at the University of Rochester. “During this period, American distributors and broadcasters quite literally channeled anime into American homes. (Think here, for example, of Cartoon Network's Toonami.) Following the 1990s boom, the global and critical success of Studio Ghibli pushed anime deeper into American cultural conversations. Rappers who came of age during this period grew up with anime and its aesthetics as a common feature of their artistic diet.”

This makes a lot of sense. My childhood anime experience was being introduced to Ghibli movies and Sailor Moon VHS tapes by my sister, before expanding into subbed Inuyasha episodes downloaded off LimeWire, and then Dragon Ball Z episodes shown on Toonami and the occasional Cowboy BeBop episode on Adult Swim. Availability of anime also grew rapidly with the invention of YouTube and other streaming services. Entire anime episodes could be posted in 4-part segments on YouTube, and websites like CrunchyRoll had some of the fastest subbing teams, which reduced the time between when the raw Japanese broadcast was released and when English speaking audiences could actually watch the episode. Anime had much more availability than I had initially anticipated, but what was it that resonated with rappers? According to Bridges, it’s a combination of art, politics, and social injustice.

At its core, anime is just another artistic storytelling medium, like painting or music: the most profound stories have a certain amount of universality to them, and usually make some sort of commentary on what’s wrong with the world, and how it should be instead. But something unique about anime as a storytelling medium is its approach. “Going as far back as the anime of Tezuka Osamu, anime has long aspired to be "mukokuseki," ("nationless"), or to tell cosmopolitan stories with infinite entry points for a vast array of audiences,” says Bridges. “In light of this history, contemporary anime tends to tell stories capaciously, and in a way that resonates with viewers the world over.”

But rappers aren’t just resonating with any good stories with universality that come their way. Many of them tend to cite Dragon Ball, Naruto, One Piece, and My Hero Academia as their favorites: classic, popular shonen battle anime. “Keep in mind that the generation of rappers who came of age with anime were also coming of age in an era when austerity politics, the fraying of social safety nets, and disinvestment in the public good collided with the legacies and ongoing realities of racial injustice,” says Bridges. “For these rappers, anime like Akira, Dragon Ball Z, Naruto, and Sailor Moon not only ask W.E.B. DuBois's question — how does it feel to be a problem? — they also answer this question with extraordinary displays of power, bravado, courage, and tenacity in the face of seemingly insurmountable social antagonism.”

In short, underdog stories about rising from humble origins to meet greatness. But not just rising to meet greatness — they’re about how one must evolve to meet greatness with your nakama (your found family). In Naruto, Naruto can’t just learn how to punch harder to fix the problems in his story, he must understand the problems within the shinobi village systems to understand why his enemies act as they do. But he can’t do it alone. In Sailor Moon, Usagi can’t just cry and complain until someone saves her, she has to face her fears and step into the responsibility of being the Moon Princess. But she can’t do it alone.

When contextualized within our greater history, it’s easy to see how stories about a young and frightened protagonist must grow to rise could resonate with African Americans living within a system and society stacked against them, who feel alone and like the world is just waiting for another reason to kick them down. In truth, it’s not necessarily that anime specifically resonate with rappers, but that rappers have the microphone to talk about anime, and can help to share their experience by mentioning what helps inspire their work.

“There's an incredible amount of interplay between hip hop and anime,” says Bridges. “There is hip hop-inspired anime (like Samurai Champloo and Afro Samurai). There is anime-inspired hip hop (like Lupe Fiasco's Tetsuo and Youth and Kanye West's video for "Stronger"). And there is the confluence of anime and hip hop aesthetics in artistic media beyond Japanese anime and hip hop (like The Boondocks and the paintings of Iona Rozeal Brown). And, since 2016, there is D'Art Shtaijio, the first American anime studio in Japan and the first Black-owned anime studio ever (founded by twin brothers Arthell and Darnell Isom and Henry Thurlow.)” Rap and anime have been intimate bedfellows, each medium influencing the other, and that definitely doesn’t seem to be changing soon. And frankly, knowing Megan Thee Stallion and Doja Cat? They’re both sure to release some banging music videos full of Jojo references or Demon Slayer inspired in 2022, and I for one cannot wait to see what’s going to come out next.

This article was originally published on