Entertainment

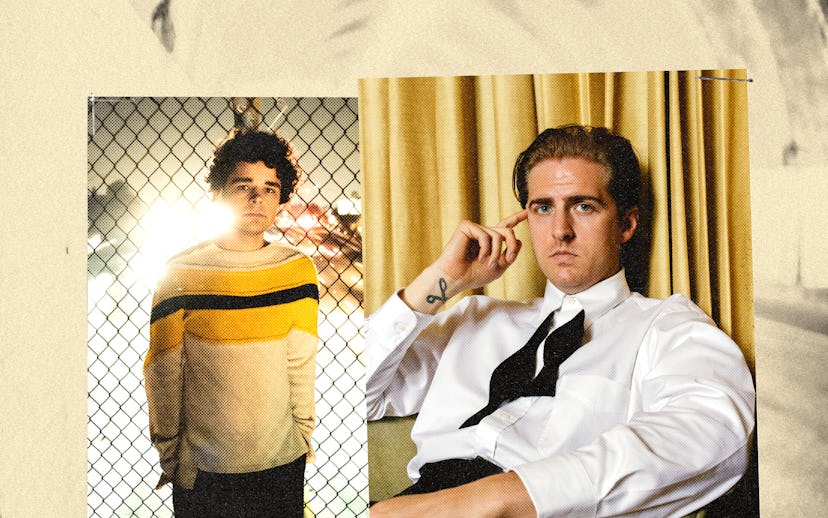

Charlie Hickey & Christian Lee Hutson: In Conversation

A deep dive into the art of songwriting.

A good songwriter can make the most complex track seem effortless. Spoiler alert: It’s not. Sure, sometimes songs will flow out, a middle-of-the-night flint that lights a spark. But most of the time, it’s work — hours poured into something that ultimately gets boiled down to the best three to four minutes possible. Charlie Hickey and Christian Lee Hutson are two prime examples of artists putting in the work.

On Friday, Hickey — who at 22 years old is the youngest signee to Phoebe Bridgers’ Saddest Factory record label — will release his highly anticipated album, Nervous at Night. Bridgers is credited as a contributor to the album, along with producer Marshall Vore and fellow musicians Harrison Whitford and Mason Stoops, who are featured on the album. Also assisting on the record is Hutson, who released his fourth studio album, Quitters, last month.

When NYLON asked Hutson to interview his friend about the new record, the singer came prepared, armed with a list of questions diving deep into the art of songwriting. Here, the two artists talk it out.

Christian Lee Hutson: One of the things that I noticed about your record is that there’s a theme of distance — whether it's someone living far away, or just a general kind of separation between the narrator and whatever he's observing. Are themes like that intentional in your writing? I know I have a specific type of neurosis when I'm writing that I'm not aware of, and if someone else were to point it out, I'd be like, “F*ck, I thought I wrote about all this different sh*t.”

Charlie Hickey: I guess part of it is that I wrote a lot of these songs when I was in a long distance relationship. They were very much anchored in the present, so there’s definitely a physical distance, but then also I think there's also a bunch of songs that sort of have that distance that comes with time or being removed from something. The record talks about childhood and the past a lot in a way that.

I feel like your songs are a lot like that, and that's one of the things I really love about them. I can maybe count on one hand the songs of yours that are about the present moment. For me, sometimes it is just too hard to write about something while it's happening, or like you don't have any perspective on it. You're just kind of like, "God, I'm still wanting to run from whatever this is." So maybe in five years, I'll be able to write about it.

It's hard to have a judgment about anything in the present moment. I've been thinking a lot recently about truth and memory and the idea that the truth is deciding what you feel about memory or whatever, and that's why multiple truths can exist and why it's so hard for us as human beings to have any accurate account of really anything that's ever happened.

Things change in your memory so much and sometimes in the moment you can totally miss what is the actual significance of something that's happening.

It changes as you get older, and I feel like songs are good markers for that. They're not good markers for, in my experience, the accuracy of an event, but they are good markers for a way that you felt at a certain time. Do you see yourself as the main character in most of your songs, or do you feel like you're writing from the perspective of someone else?

I think for the most part I do, but I'm not so attached to accuracy, in terms of my life or anything. I write a lot with others, like Marshall. “Choir Song” is a combination of the two of us. As opposed to thinking “How can I tell my life?” I'm more like, “How can I tell a story that is emotionally effective in some way?”

I was kind of going to ask you a similar question because when I hear your songs, I'm picturing you when I'm hearing them, but I know that — and you can correct me if I'm wrong — that I know you do write a lot from the perspective of others.

I will sometimes filter my own perspective through someone else's experience. It's fun for me occasionally to hear about something that's happened in someone's life and imagine that it's me and what my actual reaction to it would be.

Whenever you hear someone point out the consistencies in your work, it's always surprising. One thing that I noticed about you is you're very good at observing the people who are around you in your life. Do you feel like you see people as they really are or as a way that you wish they were?

I feel like I see people as they are, but who am I to say that necessarily? Maybe it’s just a songwriter thing or just being someone with a more neurotic, analytical brain. Being a person with social anxiety and insecurity makes you kind of analyze other people.

Do you feel aware of when the main character in your songs is revealing a flaw? I know how little thought is put into these things, and sometimes you'll just write it until it feels right, but I was wondering if there's ever that awareness. Sometimes I'll put a really ugly thing about myself in a song and it feels important to me to have it remain in the song and not have it be an idealized version of me.

There’s a line on your record, "I know, I had it all, but it wasn't enough. Does that make me a bad guy?" I feel like that's a good example of that in a way. It can be like a real risk, but when I hear other people do it, it can be really thrilling. I mean, it's like Phoebe's line about “Tears in Heaven” in “Moon Song.”

She is really, really good at doing that and doing it in a way that doesn't feel like she's an emotional shock jock.

Yeah, to really make yourself be fine with looking bad and people hearing that song and going like, "Ew, that's gross."

I really like it when songs reflect the reality of the world that we live in, not the world that we wish we lived in. Do you feel you have a responsibility as a writer to moralize things, or do you feel like a more passive narrator and that moralizing characters or situations in songs is up to the people who listen to it?

I definitely lean towards the latter. I think the responsibility to me as a songwriter is just to be as genuine as possible, whatever that means. Then on the other hand, something I struggle with is, "Oh, is it my responsibility to literally give up all of myself?" How do you maintain a personal boundary between yourself and the listener?

I'm kind of figuring it out right now. At least in everything that I've released, they are stories; they're not accurate accounts of my life. There are accurate things in them that have happened to me in every song, but they're not journalistic by any means. So I do feel protected a little bit. I can give enough of myself without it being so confessional that it's a roadmap to very private things.

What role does forgiveness play in any of your music? Maybe this says more about me than it says about you, as someone who is obsessed with that concept.

Of forgiveness?

Yeah. It's just something that I feel like shows up in my work. It was something I was curious about while listening to your album.

It's hardly ever interesting when a song is just purely angry in an un-self-aware way to the point where you're kind of like, "Oh, this person needs to go to therapy or something." But at the same time, I like songs that have a little teeth and express a bit of anger towards someone... Have you heard that new Muna song, “Anything but Me?”

I love that song. I do find myself drawn to the songs that have complicated feelings or hold space for simultaneous... like a confusing feeling about a person or a situation.

Phoebe and Marshall both have done a good job at keeping me in check a little about that at times. I’m 22. I will have the experience of being really angry about something and wanting to write a song about it, then I'll play it for Marshall and he’ll go, "In this song, you sound really angry." It’s almost easier to go to that place, and it's harder to write a song that has love for somebody.

The story of my life is trying to learn how to love people who have done bad things. I remember from when I was in high school, and still, I am a huge Taylor Swift fan, she would do that kind of sh*t really well, too — a self-righteous song that didn't come off that way. That is something that some people can do really well. Then, other people, when you hear them doing it, you're like, "I don't sympathize with you because you sound like a baby or something." I feel like that was like her whole brand in the pop-country days, which is really like addictive to me and can give you a really good feeling as a listener of like, "Yeah, f*ck that. F*ck that guy, man."

It can be like cathartic, but also sometimes I think that there's something that people miss in those songs. There's so much of a culture of somebody writes a song and then everybody goes and bullies the person that it's about on the internet.

When the extended “All Too Well” came out, Jake Gyllenhaal was trending for like two weeks straight.

Maybe “Drivers License” is a better example. Everyone was like, "F*ck Joshua Bassett!” That wasn't how that song read to me. Even her angriest songs on that album, they read to me as, “I'm momentarily really, really angry and upset, but I don't think this person is a bad person.”

It shows, as a society, how addicted we are to the narrative of just punishing people — or especially in pop culture, to villainize someone and elevate someone else while doing it. I'm addicted myself to that narrative and we'll look for those extremes in people when in reality, it's so much easier to remember with your friends and the people that you love, that everyone is a human being and everyone is full of horrible decisions and great decisions. With celebrities or whatever, or in the case of the Olivia Rodrigo thing, because there's enough distance or something, it forces you into the binary thinking that you'll have when you're watching a movie that's structured for your entertainment to have a villain and have a hero

One of the things that I wrote down that I wanted to ask you is how do you feel about your music being called sad?

I'm not that bothered by it, because I don't really feel like it's that sad. I spent so much time making Beginners, I had a lot of anxiety up to the release day of feeling like, "God, I'm scared of how people will interpret it and how people will react to it and what they'll think about it." And I'm shocked at my own reaction to it, which is that I actually don't care as much as I thought as I would.

I think it’s annoying to be thought of as a sad songwriter, and I don’t feel that I fully am, but there's a lot of pressure that gets put on people who write songs in a sad way. I noticed it with people that I used to admire and the way that I used to consume music when I was a kid, where you take somebody like Kurt Cobain or Elliot Smith, there's something kind of gross and voyeuristic about the way that people engage with them. I mean, obviously, those are two people who died in tragic ways, but even if you read music journalism about both of them before they died, there's a gross kind of almost rooting for them to be sick and be sad and be not OK. I wonder if that's not happening so much anymore now that there's a greater focus on mental health as a society. That’s something I’ve been scared of; I don’t ever want to be in a place where someone is rooting for me to fall off the stage or something.

There’s definitely times in my life where I have been in worse mental places than I am right now and have seen myself in those characters more. As you get older, you aspire more to want to be happy and healthy. But, there's this weird flip side, where it's almost like come back around in an extreme way where [mental health] is almost so destigmatized [in the way] that it almost crosses into —

Unhealthy boundaries.

Yeah. Or the people talk about being depressed and sad, and the way they link it to this music, like Mitski or whatever. It sort of becomes this cult of sadness or something, and I think sometimes algorithms of [TikTok or Twitter] kind of reward being in pain.

When I was like a teenager, it was almost like a badge of honor to be depressed and to be kind of f*cked up and out of control... the social reward of that is attention. It doesn't invalidate the depression or anything like that, but there's definitely both happening at the same time for some people. What is so funny to me is what I hear in all this music that is now categorized as sad music, like Mitski and Phoebe, is that these people all feel like champions for life and not like champions of depression.

I've heard Phoebe talk about that a lot where she's like, "I'm pretty happy, in general." Do you ever feel kind of like the risk of what you're doing being cheapened by that or sort of distilled down to a vibe or something?

I feel like that tends to happen to people, when they get just insanely popular. And I feel like I have a good amount of popularity right now where the people that do listen to me, engage with it in a realistic way. I don't think I'm at risk right now of being used as an identity for someone.

We were talking about the Olivia Rodrigo situation, the hero-villain thing. We are drawn to the things that feel really human, but the first thing that we decide to do with them is dehumanize them. It's so f*cking stupid. We are drawn to someone's humanity and then we want them to be perfect.

Obviously, you're always going to listen to things and you're going to apply them to your own life. [But,] I feel like there is something really beautiful about putting on a song or reading or watching something and losing yourself [in it] or de-centering or just it being not about you.

One of my favorite things is talking to people that have listened to my music about what they think something is about. It's almost always so much more beautiful than what it's based on or what I felt. I really do believe it in my heart that when you write a song, you write half of it, and the people who listen to it write the other half of it by filling in what isn't there and the thing from their life. In that way, you're always collaborating with someone and that's how songs can reach across time and touch you 70 years later and feel as alive as they did when they were in the studio making it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on