Next Gen: Women In Rock

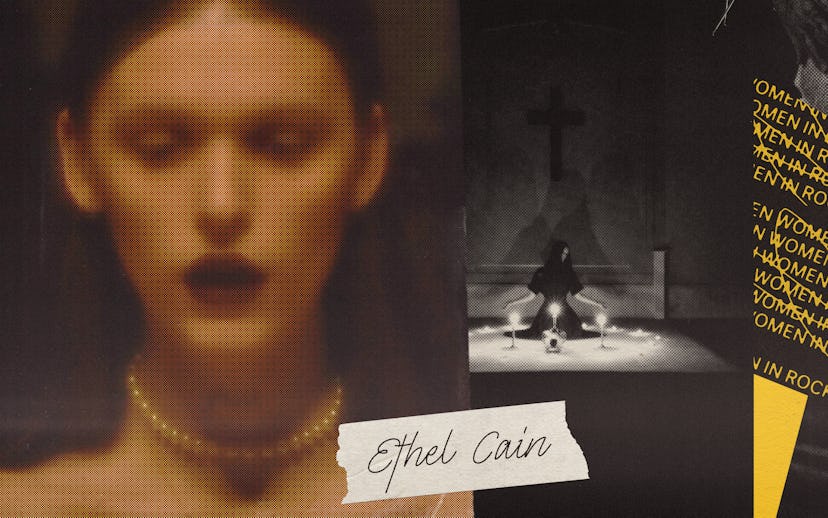

Ethel Cain Is Ready To Be Your Favorite Character

Meet Hayden Anhedönia, the mastermind behind musical project Ethel Cain.

Thanks to the Internet, a lot of today’s modern music can feel untethered from any real sense of place. And yet, that’s not the case with Ethel Cain, the musical project of Hayden Anhedönia, whose alluring and, at times, unsettling work draws direct influence from her upbringing in an intensely religious and conservative small Florida town.

Swaddled in reverb, Anhedönia’s music has the gossamer quality of a spider web hanging from a church pew. Beneath the production flourishes are beguiling, cinematic songs that play on Anhedönia’s interest in movies and building songs from scenes and characters. On recent standout “Crush,” she captures the feeling of slow, humid summer days spent pining after a dumb crush at the skatepark; “Michelle Pfeiffer” covers the pain of the kind of longing that makes you act truly recklessly.

“It kinda started backwards. I wanted to make films, but I didn’t have access to film equipment and couldn’t make them,” she says. “I was like, ‘If I were making a film and I was gonna make a soundtrack for it, what would that soundtrack sound like?’”

Anhedönia is committed to fully realizing the world of Ethel Cain, which will include the upcoming EP Inbred – out April 23 – and eventually, she hopes, books, movies, and a debut album clocking in over two hours. All of which is focused on the character she’s described as “the unhappy wife of a corrupt Preacher,” and there’s clearly more beneath the surface of Ethel to explore.

Here, she speaks about how art can be an “exorcism,” the importance of creating separation between yourself and your performing persona, and establishing a visual identity to complement the Ethel Cain sound.

You switched from making more experimental music under the name White Silas to Ethel Cain. Was there a moment of knowing where you wanted to go with Ethel?

It was pretty much an experimental phase from the beginning. I knew White Silas wasn’t going to be my name forever. I had no followers, I had no listeners. I was pretty much just putting it out to an empty room. I was like, “Do I want to make pop music? Do I want to make electronic music? Do I want to make country or indie music?” I had no idea, so I was all over the place. I played maybe two shows under that name. It was summer 2019 when I had been consistently making more and more of the alternative, indie sound and stepping away from the electronic pop sound that I had originally started out doing. I’d been ruminating on the name Ethel for an entire year during the White Silas project. So after a year I said, “I think I’ve got enough together. I think I have a clear enough version of the project I want to create.” That’s when I changed all my socials, I was like “I’m Ethel Cain now.” Ethel was brewing the whole time that I was White Silas.

Is Ethel a biblical name? Is that how you settled on it?

So Cain is, but Ethel, I was trying to come up with a name that was very ‘50s old lady. I always describe her as being the lady that sits in the front pew at church every Sunday morning. She looks 100 years old and terrifying, but she’s always there. I just felt like Ethel was such a prim and proper and poised, womanly, matronly, old American name. It felt so stiff and scratchy. That name smells like mothballs and it’s perfect. Cain and Abel was my favorite bible story growing up, so Ethel Cain had a nice ring to it.

You have a background in film, which you can see in the videos you put out, like, “Fear No Plague.” Is it very natural for you to think about how you could enhance the message of your music with a corresponding visual component?

It kind of started backwards. I wanted to make films, but I didn’t have access to film equipment and couldn’t make them. I was like, “If I were making a film and I was gonna make a soundtrack for it, what would that soundtrack sound like?” I would conceptualize a visual in my head, but because I didn’t have the resources to make it, I would just come up with the music for that visual instead and then work backwards to make the visual afterwards. Right now, we’re shooting the “Crush” music video in Los Angeles, and that song started off as a visual where you’re in high school, it’s hot outside, it’s summer. You’ve got a crush on some stupid boy and you’re hanging out at the skate park watching him skate and bust his ass. He’s a total doorknob and you’re in love with him for whatever reason. I had that visual in my head from high school and then I was like, “Okay, well what would that song sound like?”

Does your music often start with a specific character or vignette like that?

Golden Age is a little less conceptual. I was 21 and I just spent all of my time running around fields in Florida. Your brain is just swimming all the time, and it was really, really nice vibes. I feel like Inbred is very structured, but Golden Age is just big drums, big vocals, everything has massive reverb on it. I kinda wanted it to feel like you’re floating or you’re hovering through your life.

That’s where Golden Age came from, but then after COVID hit, I went sober from everything, just because I got COVID last January and I was like, “I need to get my s*** together. I want both my feet on the ground to deal with this.” I got back into the process of refining ideas a bit more and trying to get more into the details of the project instead of just having a vague, overarching theme.

Putting a macabre spin on religious imagery has long been a facet of your art. Has that always been the case?

Oh yeah. With White Silas and any projects in the past, the inspiration was always there, but I don’t think it quite translated as well. As time goes on, I think everybody naturally starts to refine their craft. [With Ethel] I really want to dive fully into this concept of the dichotomy of the stillness of the American South, how nothing moves and nothing changes. It’s all stuck in time and it’s very still and quiet and hazy. It’s really kind of peaceful, but then at the same time it’s very scary. It’s lurking beneath the water. Like all the gators, how they lurk in the water with just their eyes above it and everything else is below the surface. That’s kind of how it all feels down there.

Do you think the writeups of your music are getting at the heart of what you’re trying to express as Ethel Cain or do you think there’s room for improvement?

Sometimes I look at it and I feel like they don’t quite have it, but then I realize that all the stuff I’m basing my career off of is what I haven’t put out yet. Inbred’s isn’t even out, and I’m over here working on the full demos for my debut record that is way down the line. I’m trying to contextualize the feedback and how people are perceiving my career with the stuff that’s out and not the stuff that’s going to come out. I think for what I’ve put out so far, people are definitely getting the mark. But I feel like people will get it 100 times more once my big project is out, once the debut record is out. Inbred kind of has a story, but my record is a full concept piece. It’s like two and a half hours long. That is for all intents and purposes, Ethel Cain.

You have such a specific kind of origin story and aesthetic sense that is very different than a lot of the artists. Do you often hear from people who were in a similar position to you, growing up in an isolated place, dealing with the tensions of a very conservative background?

I get a lot of messages from people, specifically down South. They’re like “It’s so refreshing that you’re an artist who came from the exact same position that I was in going through this. It’s so nice to have someone who gets it.” I feel like that’s important.

One of the themes down South, especially, is that you don’t talk about anything. Anything that happened, you don’t talk about it. It’s a common theme that whenever you go through something, you just don’t speak about it afterwards. I think it’s nice to hear somebody say it out loud and be like, “Oh my God, me too.” It’s kind of nice to know that you’re not in it alone so you don’t feel so isolated.

Even when you were going by White Silas, you had a separation between yourself and your artistic persona. As someone who does music that can deal with very heavy themes and can have dark undertones, how do you create that distinction between your art and yourself to keep that from subsuming you?

The way I’m able to handle it is because it’s happening to someone else at that point. It’s not happening to me, it’s happening to Ethel Cain. If she’s singing about it, it’s her problem. I’ll be putting out music under my own name soon, because there’s just a lot of other projects I want to explore. Maybe less structured, less plot-related.

With Ethel, I always consider art to be a bit of an exorcism. If there are things that I feel that are a bit heavier than I feel like dealing with on the day-to-day, if I write a song about it and I make it a part of this— I call it “The Ethel Cain Cinematic Universe” — as a joke. If I make it a part of her world, her experience, then after that it’s her experience and it’s not mine. So when I sing it, it’s from her perspective, and it’s no longer personal to me.

It’s nice to have her as a character and not be portraying myself as her. Because when I first started with Ethel I was like, “I’m gonna be Ethel Cain. I’m gonna go by Ethel in interviews. I’m gonna have everybody call me that.” But then I realized that wasn’t sustainable. I think in the age of the internet, you can’t as easily be a character anymore. I love to post online, I love to show my everyday life, so it’s very obvious that I’m not her. I was like, “Let me just establish her as a character.” There’s Ethel Cain the preacher’s wife and then there’s Hayden Anhedönia, the girl behind the curtain who is significantly less dressed up.

When I first started with Ethel, it was kind of ridiculous. I was losing my mind trying to become her. I was like, “I have to be fully dressed up in these stiff dresses and little church heels all the time and put my hair in a bun and have that stiff-as-a-board attitude of a 1950s preacher’s wife.” It got to the point where I would put on a pair of jeans to leave the house and be like, “I’m not doing Ethel justice right now.” It was so ridiculous. That’s when I was like, “You need to make Ethel a very specific thing, but you also need to remember that it’s okay to be Hayden. Don’t lose your sense of humanity trying to become this very stiff woman.” It was freeing to be like, “Ethel is her own person and Hayden is her own person and you need to be able to freely swap between both when the timing is right. “

Is there a difference between where you want to take Ethel, and where you eventually want to be as Hayden, the person behind all of this?

For Ethel, at this point, she’s fully scripted. I want to do a movie, I want to do a book. I want to tell her story to the fullest extent. I know exactly what I want from her. But for me, I feel like it’s simpler.

Whenever I’m out in L.A. and I’m meeting with people, I always get asked, “What’s your 10-year plan?” Honestly, my 10-year plan is to buy a plot of land in the South, somewhere secluded, build my dream house and just be happy. I want to have a cow and I want to buy a pig. I want to have a flower garden and I want to build a little country church behind my house on my property. I want to take walks every morning and every night. I want to eat better and I want to sleep better and I want to not be so terrified of the whole world. I just want to have a little safe haven. I feel like I have very big dreams for Ethel and very quiet, simple dreams for myself. I just can’t wait for the point in my life where I’m able to sit on my front porch and drink a glass of sweet tea and not do anything for the whole day but enjoy my property and my land and my pig and my cow.