Entertainment

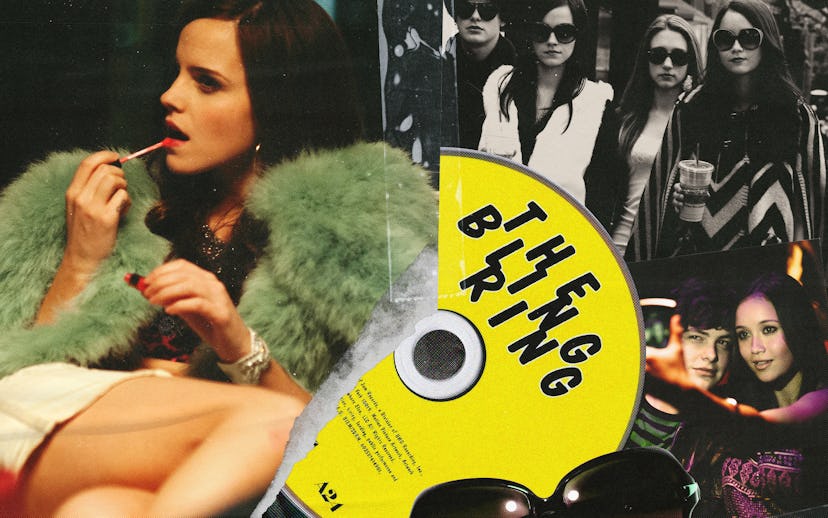

How ‘The Bling Ring’ Soundtrack Is Still Relevant Years Later

With cues from Azealia Banks and M.I.A., the soundtrack encapsulated a certain timeless, privileged teenhood.

Azealia Banks’ 2011 hit “212” remains one of the most iconic songs of the 2010s. For many, it’s synonymous with Emma Watson popping and locking in the club in Sofia Coppola’s 2013 film The Bling Ring. Playing wealthy Calabasas teenager Nicki to campy perfection, she applies lip gloss before taking a selfie on her BlackBerry and heading out to the dance floor — and the internet hasn’t stopped reposting clips of the scene in the years since.

The cult film turns 10 on June 14 and has cemented itself in pop culture because of that “212” needle drop and Watson’s incredible reading of the now iconic line, “I wanna rob.” It is also arguably Coppola’s most divisive movie. Upon release, some critics were befuddled by how the A24-distributed film seemed to focus more on style than making a clear statement in telling the story of a real group of Los Angeles teenagers who robbed celebrities during 2008 and 2009; it took time for audiences to realize the film was a satirical critique of America’s obsession with celebrity and wealth, and how detrimental that can be to formative, status-conscious youths. But even as the crime drama itself was drenched in glitz and glam, that message was always clear: it’s there in Coppola’s choice of making the new kid Marc (Israel Broussard) the audience’s entry point into the film’s flashy L.A. world — and the film’s soundtrack, which is much more than a stream of party-playlist-ready bangers.

Crafted by Coppola and her frequent collaborator/music supervisor Brian Reitzell (and scored by both Reitzell and Oneohtrix Point Never’s Daniel Lopatin), The Bling Ring soundtrack remains an expertly curated pop blitz that echoes the film’s message with every 808-heavy needle drop. But what’s perhaps one of the most interesting and overlooked qualities of it — which some cinephiles on #FilmTok are still arguing about in the comments — is how few aughts songs from when the burglaries took place made it onto the tracklist. Coppola fans have long been vocal about how “flawless” and “ahead of its time” the soundtrack was, even if it hasn’t been widely critically praised like that of some of her other films such as Marie Antoinette and its ‘80s new wave music (which appears on many best soundtracks of all time lists). Still, there’s clearly an intentionality behind this choice in The Bling Ring, too.

“For me, anything was fair game,” says Reitzell, reflecting on the cues he picked for the film. “The time frame was not far enough away that I thought it made a difference. It was 2008, and here we were in 2012, 2013 making the movie.” For him, curating the tracklist was simply an “awesome” experience because he had long wanted to do a film using more modern music like rap.

The closest song to what might’ve been on the actual Hollywood Hills Burglars’ iPods ended up being Ester Dean’s 2009 track “Drop It Low,” which plays while Marc records himself dancing and smoking a bowl to on Photo Booth. That song was written into the script to reenact a real video that surfaced on TMZ.

But most of the film’s other tracks are drawn from 2010 and onward, when its source material, Vanity Fair’s “The Suspects Wore Louboutins,” was published. Sleigh Bells’ “Crown on the Ground” plays in the opening sequence as the gang tears through an A-lister’s closet; songs from Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy soundtrack scenes where the teens feel invincible, singing along to the radio or on one of their shopping sprees; hits from the early 2010s like Rick Ross’ “9 Piece” and several M.I.A. staples dot its scenes. Even underground R&B anthems from 2013, when the film was released, like Frank Ocean’s “Super Rich Kids” and School Boy Q’s “Hell of a Night,” snuck their way onto the final tracklist. Alongside a fair share of krautrock and Lopatin and Reitzells’ synth-y score, these songs captured a sprawling and indulgent L.A. landscape.

The soundtrack encapsulated a certain privileged teenhood as they cosplay gangsters while barreling through traffic on the 101, thinking they can do anything without consequence. But, in its unrestricted selection of songs, it also illustrated how pervasive — and timeless — the film’s message is: that youths are, have been, and will always be fed an obsession with hedonism and status. Even though M.I.A.’s “Bad Girls” was released in 2012, the lyrics “Live fast, die young, bad girls do it well” may as well have always been, and still be, their mantra.

It took time for audiences to realize the film was a satirical critique of America’s obsession with celebrity and wealth, and how detrimental that can be to formative, status-conscious youths.

Kanye West’s involvement is another oddly prescient aspect of the film’s soundtrack. His 2010 song “Power” plays as the fivesome struts down Rodeo Drive, and Marc and Rebecca (Katie Chang) sing along to “All of the Lights” on a late-night drive. But Reitzell says that “Kanye’s fingers are all over [the] movie,” beyond just those two songs.

The latter was written into the screenplay and mirrors the film’s themes, with its lyrics being an indictment of fame, and Coppola saw it as pertinent to the film. Reitzell says he was aware of the battle it would be to get the song licensed, with its long list of credits, and was discouraged by the label to try. But when it came time to film the scene of them singing that song, Reitzell says, “I rolled the dice thinking that if Kanye would say yes, then all the rest of [the artists credited] would say yes. Luckily, that worked out because he said yes literally the night before we shot [the scene] and Sofia said, ‘Let’s just shoot it.’” (Frank Ocean, whose “Super Rich Kids” was also put onto Reitzell and Coppola’s radar by West before it was released, only came on board after West’s urging.)

Originally, Reitzell says, they tried to make West an executive producer on the film. “We wanted to bring him in, [have him be] more involved," he says. But it ultimately didn’t work out because of how busy he was in the fashion industry at the time. In retrospect, West’s omnipresence is fascinating, given his level of celebrity — which has only quadrupled and taken on new, warped meanings since.

“It was very meta,” Reitzell adds. “He was such a big star at that time — I mean it was ridiculous. But he was cool to us.”

Songs like “212” and “Bad Girls” now live on largely thanks to The Bling Ring. “212” has appeared in other movies since (A24 passed its needle drop to Bodies Bodies Bodies last year), but those inclusions still barely hold a torch to Nicki awkwardly letting loose in stilettos.

“Emma Watson loved that song. I think she may have even requested it,” Reitzell says. He remembers bringing it to set the day they filmed the scene (which was a rare occurrence, since he tends to prefer working out of his recording studio and music supervisors rarely come to set at all). And while its resonance wasn’t necessarily clear at the time, he thinks “it’s awesome” how memorable the scene has become because he could see how much fun Watson was having. “She wasn’t just acting, it was real!” he says.

Those clubbing scenes, interspersed with ragers at Lindsay Lohan’s and actual TMZ footage, may have made the film seem frivolous and vapid. But there’s an artfulness to a small budget project opening to shots of bling and the brash tunes of “Crown on the Ground” and featuring moments like that of a blonde valley girl rapping to Rick Ross only to reveal she lives in what looks like the Versailles of Calabasas. As it goes in The Bling Ring and reality, the super rich kids with nothing but fake friends will always be driving through L.A. traffic, blasting loud music, and looking to tabloids to see what’s cool — whether they’re going to Paris’ or not.