Life

Dreams And Duty: How Speaking Different Languages Keeps Me In Touch With My Past

Finding a way through sentiment and vocabulary

For 12 years of my life, I awoke to the same routine. A gentle knock on my door, followed by a more urgent one, quickly followed by the hinges creaking open and my mother exclaiming in harried frustration, “Bo Shami! Reveille-toi!”

I would wipe the crust off my eyes, step into my slippers, and sleepily reply, “Bonjour, maman” with an obligatory kiss on the cheek. If a guest was visiting from our homeland of Comoros, I would then step into my living room, with my right palm over my left extended in their direction, and demurely state “Kwezi,” dutifully waiting for the obligatory placement on top of my hand and subsequent “m’Bona.” Then I would shower, get dressed, and step out into the courtyard of Colonial (now known as Ralph Rangel) Houses in Harlem, where my friend Ashley was waiting to walk to the train with me, chattering away in English about what we had watched on TV or heard on the radio the day before.

This cadence of flowing between three languages before 9am is not unique to me and my family. Comoros Islands, the East African “Islands of the Moon” nation where most of my family resides, has a history whose legacy is influenced by the fluctuations of the lingua franca throughout time—from the local Swahili dialect spoken amongst our four islands as an outgrowth of the famed Swahili trading coast (shingazidja, shinzwani, shimaore, shimwali individually–shikomoro collectively) to the classical Arabic language and script that came with the expansion of Islam in the 10th century, followed by France’s colonization of the region in the 1800s and the combination of a colonized outpost with Madagascar. In the capital city of Moroni, the conversion of this linguistic history makes its own music: Islamic elders conducting business affairs in Arabic; diplomats, scholars and journalists communicating with the Francophonie in formal French, evidence of their access to elite schooling; migrants transitioning between the Austronesian Malagasy language, the remnants of our colonizers moving us back and forth between the two distinctly different nations like pawns on a chessboard, picked up and displaced at the whims of Europeans' export needs up until the 1970s. My name, Shamira Ibrahim, its original spelling, Chamira, and the familial affectations I am commonly called—Bo Shami, Bo Shamu, Bo Sha—are the manifestation of these exchanges.

These languages are my connection to the diaspora, my link to my own displacement, as a first-generation child whose mother unexpectedly landed in Montreal, and then Harlem, New York City. We live in Harlem, a dense populace that is, however, simultaneously sparse of a Comorian migrant community. This is as opposed to the Mediterranean urban enclave of Marseille, France, home to approximately 50,000 migrants from an archipelago that holds 800,000. A walk through Marseille’s Noailles neighborhood offers the chance to overhear boisterous conversations in French cut through with excited exultations of Hufanyiha dje?! (How are you?!) Traversing these neighborhoods with my cousins this past May came with a particular sense of melancholy and a twinge for the lingual community I was denied. My affinity to the language has been reduced over the decades to barebones conversation and general subject matter, akin to attempting to read a vision chart from afar without glasses, and using the edges of the shapes to contextually fill in the missing information—with middling confidence.

While I may have lost my shingazida, I still held tight to my French, my shifaranza or mother tongue. I was born in Montreal and moved to New York as a child with a parent who wasn’t comfortable speaking English at home, and who had found a Francophonie Muslim community in Central Harlem, full of Senegalese, Guinean, and Malian men and women whom I would come to call Tata and Tonton. I could read and write in English, but preferred to respond in French. Upon threat of being placed in ESL classes in elementary school, my mother and I tempered ourselves, tucking our modulations away from public consumption, with my mother taking the additional fearful step of speaking primarily English in the household. But regardless of what I was saying externally, I still thought, dreamed, and hoped in French, dutifully going through the occasionally laborious exercise of putting sentiment to paper by transmuting my thoughts between tongues, leading my teachers to be convinced I had remedial writing skills as opposed to a disinterest in the workload required.

One day, that all changed. I can’t pinpoint a date when that switch happened, but my association with my native tongue suddenly morphed from the inherent reflection of my spirit to one of etiquette; the mode in which I dutifully answered calls from my cousin in Lyon and my aunt in Marseille, exchanged cordial emails with yet another cousin in Syria, murmured demure deferential accordances with the extensive network of relatives who were invested in the comings and goings of the firstborn daughter of Maman Shamira. When I exhibited internal annoyance at the notion of having to wake up at 6am to answer calls from family eight time zones away, that irritation fired through my synapses in English, same as when I had to spend the bulk of my Sundays faithfully memorizing the various Surahs of the Qu’ran and repeatedly tracing the corresponding Arabic scripts. The connection had turned into a ball and chain, tied to my family obligations and perceived requirements of propriety as the eldest daughter of a family cherished from two oceans away.

Rediscovering my relationship with French in adulthood was a metamorphosis that spanned seasons, from forcefully inserting myself in French classes that I conversationally placed out of for the purpose of exercising a writing muscle that I rarely used in favor of extended dialogue of the years to coming to terms with the erosion of my accent over time, as I have gone from a hybrid Quebecois/African Francophonie lilt to one with distinct American intonations. My tongue doesn’t vibrate against the roof of my mouth the same way to create the iconic guttural “R” that is intrinsic to the language anymore. My nieces and nephews (children of my innumerable cousins) are regularly amused by Tata Shamira’s overly formal oratorical style, liberally applying the third-person formal vous with little discretion, declining to engage in the common elisions and excisions that colloquially contract the syllables required of a standard sentence fragment, rounding out every sound of il n’y a pas instead of the breezy nyapas. Language, as a concept, is a sentient, evolving, redefining concept, molding and shaping to regional rhythms at paces faster than the average iOS update. But my French, the French I used to connect with my elders, was a snapshot in time, a sentiment similar to photocopying a document 10 times over; the outline and content may be the exact same, but the pigment is fading, edges fraying, and a tint has applied that makes it identifiably differentiable from the original.

With the ascent of social media and escalating presence of the Francophonie in social media, I’ve been able to make significant strides in bridging that gap. I no longer look with confusion when my nephew sends me mdrrrrrrrrr on WhatsApp, an indication of mirth that did not exist when I was in my elementary years. Consumption of present-day music and news exist as my pipeline to the emerging trends of linguistic phrasing, of which I will not be guaranteed exposure to by merely relying on my lengthy exchanges with aunts and uncles. It will never feel like it once did—an inextricable component of my spirit—but I have embraced my new relationship with it the way you do a cousin who you grew up with, but may have moved away from for a few years. There are days when I feel stuck between two rhetorical worlds, struggling to translate a French sentiment into English or vice versa—translating the lyrics of Jacque Brel’s iconic "Ne Me Quitte Pas" can take the punch out of a line as arresting as “je t’inventerai, des mots insenses, que tu comprendras,” while being asked to translate English portmanteaus, such as "misogynoir," derived from modern critical black feminist theory renders me using more syllables to describe it than would be preferable. But in this final transition of my metamorphosis, I’ve unveiled a new tongue for myself, one that is neither 100 percent French nor 100 percent English, but instead operates on a sliding scale depending on my environment, free of any prior varnish of the modality required to phase in and out of any of them, continuously connecting me to my community in its various existences and compositions. And when it comes to my dreams, sometimes they are in English, sometimes they are in French, and other times they are endless loops of lyrics to my favorite twarab songs in shingazidja, evoking a sentiment more so than a vocabulary.

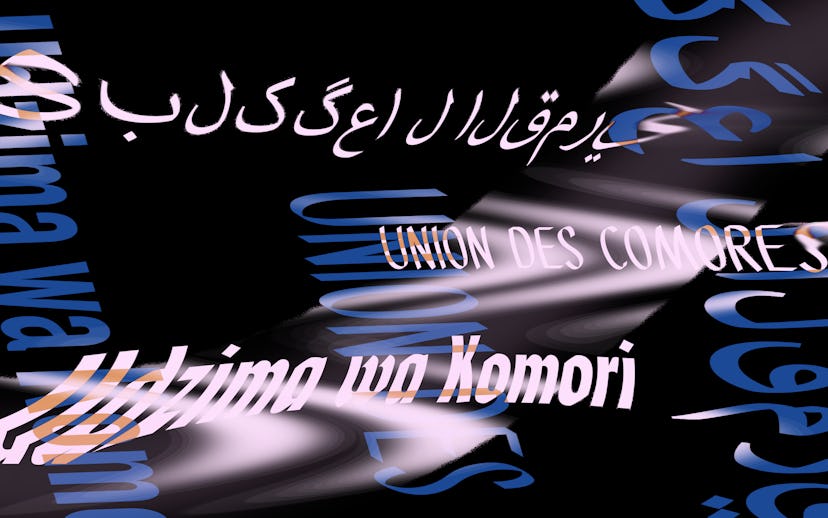

I have so many names for my homeland across so many tongues: Comoros, Comores, Udzima wa Komori, Massiwa , Juzur al-Qamar (جزر القمر). I once felt the need to segment my Comorian diasporic existence in what each tongue represented for me: English as the language of my day-to-day, French as the language of deference to elders, Arabic as the language of obligatory recitation. Time and growth has enabled a fluidity and blurring of these boundaries as amorphous as language itself, and still every bit as connecting to my greater community. There are days where I recite the basmala—bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm (In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful)—more times in one day than I greet people in English, just as there are instances when I read something in French and struggle to find an equitable way to translate the exact same sentiment to my non-French speaking friends, resigning my association to the language as one of intrinsic comprehension but not academic conversion. And while shingazidja is the most faint to me, it is the tether to my eldest aunt—who never had the privilege of formal schooling, and for whom French exists merely as the indiscernible language of her former overlords—and the means by which I look forward to greeting her in person during my upcoming visit, with palms outstretched as I have done since I was four years old. I may present differently in each language, but I love as a Comorian, equally, in all of them.