Culture

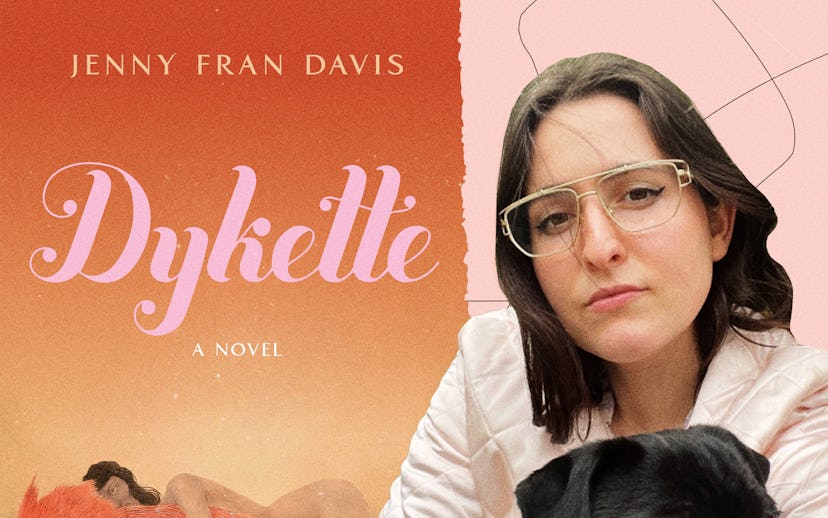

In Dykette, Jenny Fran Davis Captures When Life Becomes Performance

In her bold second novel, Jenny Fran Davis takes on the seduction and banality of normativity and edginess.

Jenny Fran Davis is always thinking in references. Her brain is “endlessly referential,” processing what’s going on in her life through books and movies, which she says always seem to have already expressed whatever she’s feeling more eloquently. “Everything makes me think of something that already exists, and then that makes me think of something that's already existed before that,” she tells NYLON. “Everything feels like it’s in a loop, referencing both itself, past things, and even present things that are going on at the same time.”

Enter Sasha, the protagonist of Davis’ new novel, Dykette. Sasha is a PhD student who studies literature and travels with her partner, Jesse, and two other queer couples from New York to en vogue, offbeat Hudson to celebrate the holidays. The house oozes the stuff of coupled, settled life: blood orange negronis and “the types of books that appeared on top-ten lists,” and an open floor plan. The couples spend their days cooking, chatting, watching movies, and soaking in the backyard sauna. Every interaction is charged by the overlapping currents of what’s going on between them all — romantic interest, mentorship, competition.

The trip comes at an important juncture in Sasha and Jesse’s relationship. They find themselves cycling through fights that oftentimes result from Sasha’s “high-femme camp antics.” Sasha relates to the world through performance — games, roleplay, and her various personas, including an Eastern European housewife. She theorizes her own life through Gossip Girl and Stone Butch Blues and Chloë Sevigny. Confronted with the models of her queer elder hosts, Jules and Miranda, and the arty influencer ilk of Darcy and Lou, Sasha finds herself at cross-purposes, pulled between the poles of performance and sincerity, which, increasingly, she struggles to distinguish.

Dykette is a book that makes you want to read, to see what other references and texts can help you make sense of life. While Davis claims that books and movies have already expressed whatever she wants to say, her novel clears the fog on a life lived between imperatives, or a life lived with multiple imperatives. In crystalline prose, she depicts the intricacies, dualities, and contradictions of relationships — both intimate and platonic, romantic, and adversarial — all with a wicked appetite for humor and camp. Through her hyper-specificity, Davis captures how uncanny one’s life can begin to feel to oneself.

Ahead of the book’s release, she spoke with NYLON about nonconformity, normativity, the texts that inspired her, and the language around representation.

Dykette is full of Sasha thinking about other texts, movies, books. What media was on your mind as you wrote the novel?

I feel like everything from new novels to more theoretical works. A couple of movies were super influential, like Bound. Jack Halberstam’s Female Masculinity. Persistent Desire, which is an anthology of butch femme writings from the ‘40s to the ‘60s. Ethnographies like Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold. The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall. I reread Stone Butch Blues. I forced myself to read all of the classics that I hadn't yet read.

I couldn't decide between going for my MFA or my PhD in literature. Having the protagonist be in a PhD program was a way for me to cosplay as a PhD student, see what it would be like to merge academic theory and scholarly texts with campy, fun, gossipy novel writing. I'm still dreaming about getting a chance to go into a super academic program and shut myself away for, like, five years and read all of the theory and historical documents and get into the archives, all of those things I’ve always been really obsessed with.

There’s something really interesting with this book with the creation of self against media or other people. It’s a mechanism for the self to coalesce.

Totally, and I often feel like most of the things that I want to say or express have already been said and expressed so perfectly and beautifully. I'm definitely an over-quoter. There's an endlessly referential quality to my brain; everything makes me think of something that already exists, and then that makes me think of something that's already existed before that. Everything feels like it’s in a loop, referencing both itself, past things, and even present things that are going on at the same time.

I also thought about this book in terms of materials and materialism. How do you think of objects as a performance of nonconformity and normativity?

That's such a good question, and definitely something I thought a ton about. Objects feel so central to the ways that we think about ourselves and other people, and in that way they actually don't seem inanimate at all. They seem very full of life, meaning, and personality. I think that the materialism of the characters at first glance might seem shallow or superficial, but objects carry a ton of meaning and association for the characters. They're often a really good shorthand for emotion. It's almost like not looking directly at the way a character is feeling but imbuing an object with the rage or jealousy or infatuation that a character might be feeling.

The things people wear and the things they put in their homes are performative because they're meant to signal, “This is me, this is who I am, this is what I care about, this is what I can afford, this is what I think looks really good.” It’s sort of like an aesthetic statement, but also, I think in a lot of cases, deeply real. That was something I was really fascinated by: how can this super defined and hyper realized material world not feel shallow and materialistic, how can that feel deeply lived-in and important?

Inclusion and exclusion within the lesbian and queer communities were an important thread of the book. How were you thinking about that?

I think I felt a lot of anxiety about representing a community, slash my community, of lesbian, queer, Brooklyn, my age group — I felt hesitant and anxious to even attempt representation in full. It felt impossible, and it also didn't quite feel like a useful goal. I have found that in a lot of coverage of novels and memoirs that are not mainstream in whatever way, there's a lot of talk about seeing yourself if you're a member of the community, and the importance of representing X community in X way. I think I really leaned into hyper-specificity as a way to resist the pressure or the expectation to represent everyone. Instead, I relied on my skills that I've always had, observing really closely, and then faithfully documenting what I saw, not in the great wide world, but in a group of friends. That was something that I made peace with really early on — this isn't a wide swath representation of anything or anyone's community.

I really loved your essay in LARB. You write, “Television shows us girls-on-girls being girlie, but in a lesbian way, which is to say that these girls don’t just f*ck each other, but more so f*ck with each other.” Putting six people in a house, there are different kinds of desire and jealousy. What were you interested in playing with in the setup of your novel?

I think that is a really great summary of every conceivable dynamic in this house. There's certainly sexual attraction, but beyond that there's infatuation, jealousy, and this sort of classic queer thing: do I want to be this person, or do I want to be with this person? There’s a desire for recognition, but there's also just desire, and I think that those things can get really confusing, especially in context of intergenerational friendship. What might I grow into? What did I used to be?

Another thing I was really interested in was the extent to which other people will always be opaque to us, like maybe we can clear away certain things and maybe people come out in their full, naked desires, but how even the expression of those things can feel really superficial. I guess a big dynamic is exploring how can people be at once absolutely performative and absolutely sincere at the same time?

One line that I thought captured this was, “Sasha was playful, engaging with persona, being funny. It was funny! This was all fucking funny!” What role do irony and persona serve in her relationships?

In a lot of ways, irony and persona are the primary modes by which she interacts with people. We see her game outplay her by the end. There's nothing left to perform, but there's also nothing more sincere than performing for her. For whatever reason, it's how she engages with the world. And like any way of interacting with the world, there will come a point that the world just becomes completely disorienting and illegible to you.

I think for her, the game she's doing often is successful. She makes people laugh or endears people to her, gets what she wants or defuses tension. I think it's interesting to see a character come to the end of their rope, to suddenly find themselves in a place where the thing that they've always done does not work anymore. Will they try again and again, or will they give up? Will they change? That’s the question that we leave her at, and hopefully we've gotten to know her well enough to guess what she might do.

The attention to language in this book is really sharp, whether with humor or the sense of language being fleeting. Visibility is called “a word that everyone loved then.” What are you thinking about with language in the discourse?

The novel self-consciously dates itself and places itself in a particular time and geographical region — it knows that everything it's saying is a product of its time. I think that in terms of the individual moments of language, those often are to access humor or refer to a really specific cultural phenomenon that contemporary readers would understand and connect to. But I think the critique might lie in the refusal to make anything feel universal. It's not trying to say that the words we use right now are any better or any worse than words people have used in any other time or place. I think it's stressing that this is the language that's meaningful to us now, and here's why. And that's sort of all a writer can do.

What’s exciting to you in your reading and writing these days?

I've been reading a lot of very fast-paced, plotty books. For me, that's the ultimate escape and relaxation, and it's the best thing for anxiety to just get completely lost in another world. I've really been interested in the inner worlds of characters that are unacceptable in some way to readers. I think a lot of — especially women — writers have been creating characters that are despicable in some way or extremely out of touch or out of line. There’s this sort of unhinged female narrator trend, and I'm really interested in that. I never find these women despicable. I often love them, and I don't even realize that they're supposed to be crazy or terrible until other people point it out. I'm really interested in what happens when that character meets the moralizing instincts of a lot of contemporary readers. What do we do now that we've come to a place that so much of writing is deemed good or bad, acceptable or unacceptable, moral or immoral, ethical or unethical, all of these super arbitrary distinctions? There’s this sort of quiet resistance, I think, on the part of a lot of writers to make characters who are completely not adhering to social norms or moral, ethical norms that so much of our real lives are governed by.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on