Culture

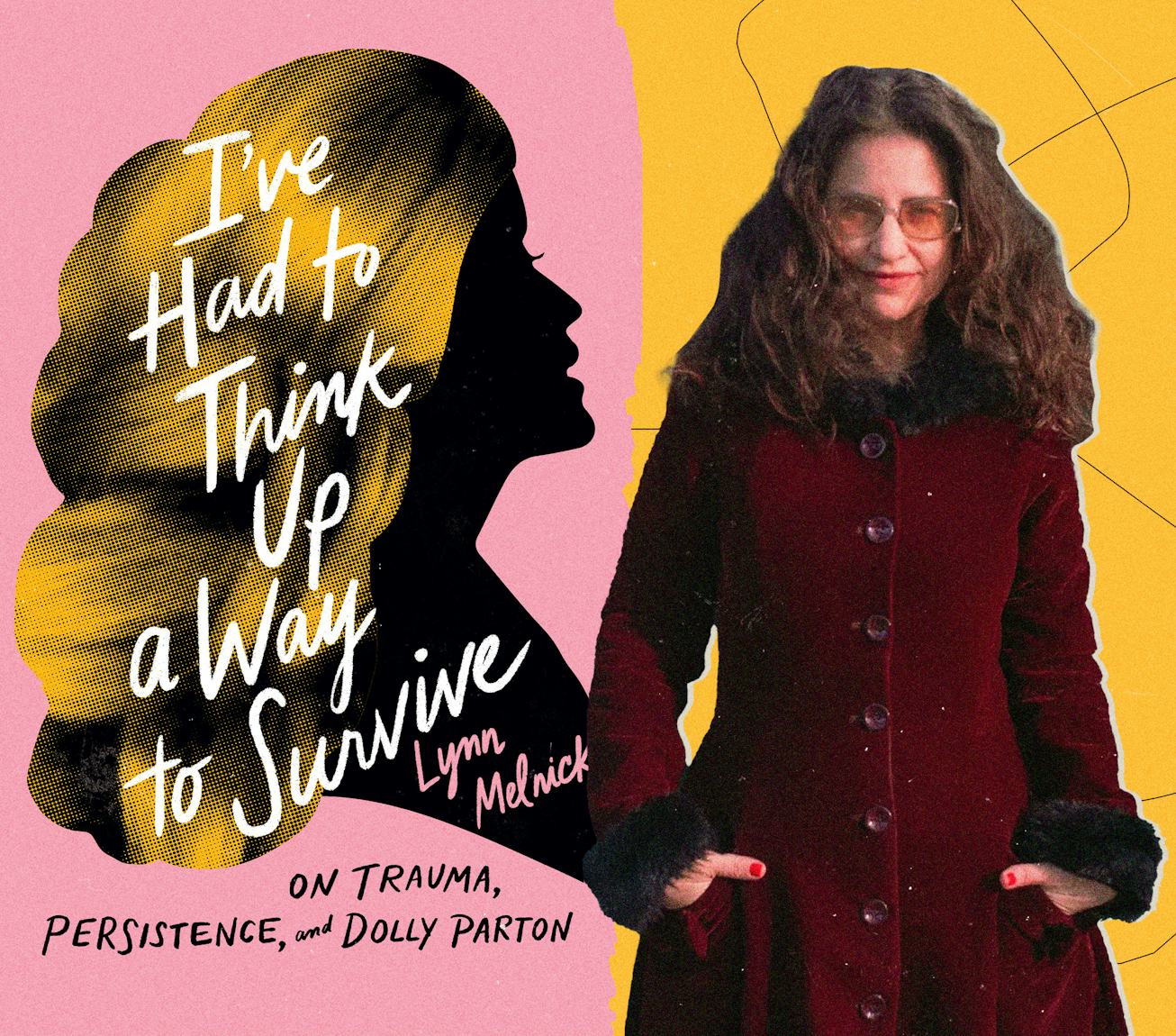

Read An Exclusive Excerpt From I’ve Had To Think Up A Way To Survive: On Trauma, Persistence, and Dolly Parton

Lynn Melnick shares “The Bargain Store,” a chapter of her memoir I’ve Had to Think Up a Way to Survive: On Trauma, Persistence, and Dolly Parton.

I’ve been handcuffed and placed in the back of a police car exactly once in my life. I was fifteen, it was December 1988. My friend Kimmy and I were on a street in Hollywood when we should have been in school. We were being goofy kids, laughing about something, feeling happy just to be alive, despite everything, in a way only a kid can. We somehow, despite the shit, hadn’t shaken the wonder. Kimmy was a year or two older than me; we’d met in drug rehab. She’d been selling sex for a while. We were not dressed like you might imagine—I was wearing a long white T-shirt and white leggings and knockoff Keds—but I guess this was a corner, and a man slowed and asked how much we charged. I’ve always been a lightweight drinker, and I think I’d had one beer, maybe two, and I was tipsy and I don’t remember any of what we said to that man but he was an undercover cop and off Kimmy and I went to the police station. I was terrified; I imagine she was too.

When we got there, it had the same cinderblock bleakness as my drug rehab, as my middle-school cafeteria, as the basement bathroom of my parents’ synagogue. Kimmy, whose mother had brought her from Mexico into California as an infant and then worked impossible hours at a manufacturing business downtown, was put into a holding cell. It was a small precinct, and I could see her in there staring at me. It was literally the first time it occurred to me that my whiteness had benefits. Kimmy had committed a crime, whereas I had made a mistake. A white female cop brought me a can of Coke, which I sipped slowly, not looking up at Kimmy or anyone else. Eventually, a male cop came over to me, told me to leave, get my act together, and he didn’t want to see me back there ever. You’ve got your whole life ahead of you, he said. Having my whole life ahead of me was far too abstract. I didn’t think past the next day. I never saw Kimmy again.

Dolly Parton often tells a humorous story of being mistaken for a sex worker when she was on her first trip to New York City with her childhood friend Judy Ogle in the late 1960s. Always up for an adventure, Dolly and Judy decided to check out one of the porn theaters on Forty-Second Street. This would have been in the ’60s, well before Times Square was turned into what Hollywood Boulevard also turned into, an overdetermined gathering of chain stores mixed with whatever life was left gasping in a storied history. Somewhat mortified once the porn started—supposedly because it turned them on and they weren’t with their partners—the two women left the theater. One of Dolly’s recurring bits is that she modeled her look on the town tramp, trollop, prostitute. She uses different words for sex workers depending on the interview. She loves to tell the story of how her parents, when she asked them about a woman who stood all dolled up on a street in her small town, replied, oh, she’s just trash. And Dolly thought, that’s what I want to be when I grow up! Trash! Dolly thought the sex worker was beautiful, and still does. “I had never seen anybody, you know, with the yellow hair all piled up and the red lipstick and the rouge and the high-heeled shoes, and I thought, ‘This is what I want to look like.’”

Dolly has told this story in more interviews and talk shows than I can sensibly list here. She told this story at her well-loved (turned into a book!) University of Tennessee commencement address in 2009. She included this anecdote in her Hallmark Channel movie Christmas of Many Colors, in which she herself plays the woman whose style she most admired. “I’d never seen a painted angel up close before,” says Dolly in a voice-over. “Especially not one driving a red Thunderbird. But I never stopped dreaming of looking just like her.” (Wink, wink.) By the time Dolly and Judy got to Times Square, Dolly says, she hadn’t realized that prostitutes ran in pairs for their own protection, and men kept coming up to the two of them, thinking they were available. “They thought we were for sale,” she told Playboy in 1978, looking back a decade earlier. “You can imagine how ridiculous I looked, I would look like a streetwalker if you didn’t know it was an image. I would look like a total whore, I suppose. . . . But I had a gun. I never traveled without a gun, and don’t. I always carry a gun.”

Several years later, in January of 1975, just before Dolly’s twenty-ninth birthday, her song “The Bargain Store,” from the album of the same title, was released. Presumably the song positions Dolly as a thrift store: worn, but if you search you find treasure, love, and satisfaction, and, what’s more, it comes cheap. Likely meant more as an analogy for older or divorced women—women who had been through some stuff, who were not virgins, who might have been thought of as used goods—it was interpreted by many country radio stations as a song about sex work and was banned from the airwaves. While the meaning of “The Bargain Store” was misconstrued, I can’t think of a single celebrity who has been so openly supportive (and sometimes even celebratory!) of sex workers; certainly none of Dolly’s icon status. Dolly has written and recorded songs explicitly about prostitution, including 1969’s “Mama Say a Prayer,” about a lonely girl who moves to the big city and falls into sex work, and 1982’s “A Gamble Either Way,” about a girl abandoned by her parents who feels unloved and unnoticed until she has a body to use for the pleasure of others.

Dolly isn’t always great on the subject of sex work. Using words like “trollop” and “trash” throughout her career to talk about the sex worker who inspired her look isn’t exactly unharmful, even when the words are said with love. She can be a little judgmental, as in her 1981 cover of “The House of the Rising Sun” and her 2019 collaboration with Christian alternative rock duo For King & Country on “God Only Knows,” for whose video Dolly plays what she would call a “trollop” or “fallen woman.” The message of both of these is that God forgives but sex work is a sin. Yet even this notion, the forgiveness, is a radical statement in some communities.

Dolly’s 1982 movie musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, adapted from the 1978 stage musical, is based on the true-life story of sensationalist investigative journalist Marvin Zindler’s 1973 takedown of the Chicken Ranch, a brothel that had operated somewhat openly and without incident since the mid-nineteenth century near La Grange, Texas—located kind of in the center of a Houston–San Antonio–Austin triangle. Coming off the success of 9 to 5, Dolly’s first film, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas was also a hit, knocking E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial out of the number-one spot at the box office. I was eight when those movies came out and spent almost the entirety of E.T. crying.

I wasn’t aware of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas at the time, even as it enjoyed the biggest opening weekend for a movie musical ever up until that point and went on to be the most successful movie musical of the 1980s. It also scored Dolly a Golden Globe nomination despite its mixed reception. In a review in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert complains how unsexy Dolly is in the movie. There is zero chemistry between Dolly and Burt Reynolds—they apparently did not get along well in real life—and Dolly lobbied to add an actual kiss between them. For the fans, she said. It all seems perfect on paper, two huge sex symbols in a movie about sex. But there’s no accounting for chemistry.

“There are a few funny jokes, some raunchy one-liners, some mostly forgettable songs set to completely forgettable choreography,” notes Ebert at the end of his review, “and then there is Dolly Parton. If they ever give Dolly her freedom and stop packaging her so antiseptically, she could be terrific.” He’s right. Most of the time, Dolly seems too reined-in in the movie. It is during the moments where she is off the cuff— when she’s Dolly—that she truly shines. There’s a scene where Dolly and Reynolds go out to the country to get drunk on beer and they have a conversation about Jesus being good to fabled biblical prostitute Mary Magdalene and it was ad-libbed, which isn’t a surprise, because not only does Dolly seem the most natural in this scene but her politics come out whether she likes it or not. “That’s funny now how God can forgive you, but people can’t,” Dolly, as the madam, Miss Mona (Miss Edna, in real life), says to Reynolds’s cop character.

“She liked her ladies to treat her customers real good, but never in an unladylike way,” the movie’s narrator tells us in the beginning of the film, and that is certainly the scrubbed-down version of a brothel. Still, the movie was hard to market because “whorehouse” was considered a dirty and taboo word in many places at the time. In a recent interview, actress Kristin Chenoweth says of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas and Dolly’s part in it, “She managed to make a movie, a story about a whorehouse okay, acceptable, hilarious, and heart-warming. Who else could do that but Dolly Parton.”

The movie is surely hokey, corny, predictable, and super ’80s-tastic, with the women (besides Dolly, who is always in Dollywear) in off-the-shoulder blouses and clashing Lycra ensembles that look like they’d make a lot of sense on the VHS of Jane Fonda’s Workout, which came out the same year. It’s also kind of progressive. At one point there’s a conversation about whether brothels are obsolete because of the sexual revolution. After the scene where Dolly and Reynolds fight and he calls her a whore, we hear an instrumental version of “I Will Always Love You” and then it cuts to a news report about decriminalizing sex work, which even uses the word “feminist.” “You can’t legislate morality,” Reynolds’s character argues to the governor of Texas.

Edna Chadwell, on whom Dolly’s character is based, hated the movie. “There was nothing about it right except that it happened in a whorehouse,” she said. In Dolly Parton, Gender, and Country Music, Leigh H. Edwards writes, “On one level, it cites feminist arguments for the decriminalization of prostitution. It rewrites a familiar, gendered Hollywood film script by widening the definition of who can count as a heroine . . . Yet, on another level, the resolution reiterates a common film trope in which the male character legitimates and reforms the female ‘hooker with the heart of gold’ by marrying her, restoring a gender hierarchy within a romance plot.” It still seems like a victory for sex workers that the story was told with such an absence of shame or squeamishness. I wonder if such a movie could be made today; later in the same recent interview, Chenoweth talks about how the movie 9 to 5 supported a change for working women, “and not the bad kind,” she says, tellingly, “not the one in the whorehouse. The one in the office buildings.”

In 1973, ZZ Top recorded a terrible song about the Chicken Ranch called “La Grange.” In general, though, the 1970s were a good moment for thinking about sex work (even badly, I guess). The Sunset Strip music scene, as I experienced it in the 1980s, featured a lot of songs about strippers and strip clubs, songs that confused my young friends and me about a woman’s worth, but the 1970s were kind of a golden era for songs about prostitution. Lou Reed’s 1972 “Walk on the Wild Side” (about queer and trans sex workers associated with Andy Warhol), Steely Dan’s 1973 “Pearl of the Quarter” (about a man in love with a sex worker in New Orleans), Labelle’s 1974 “Lady Marmalade” (which Patti LaBelle claimed she didn’t know was about a prostitute when she recorded it), Queen’s 1974 “Killer Queen” (about a high-end call girl), Leonard Cohen’s 1975“Don’t Go Home with Your Hard-On” (about being raised in a brothel), the Ramones’ 1976 “53rd & 3rd”(about male sex workers in Manhattan), Blondie’s 1976 “X Offender” (in which the sex worker falls for her arresting officer), Kenny Rogers’s 1977 “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” (about the grateful son of a single-mom sex worker), Nick Gilder’s 1978 “Hot Child in the City” (specifically about walking the streets of Hollywood), the Police’s 1978 “Roxanne” (inspired by street sex workers near Sting’s hotel in Paris), and Donna Summer’s 1979 “Bad Girls” (about street sex workers on the Sunset Strip) are truly just a selection of the many 1970s songs about this subject. Many of these were hits.

“The Bargain Store” reached number one on the country chart in early 1975 and stayed on the chart for nine more weeks. It also reached number thirty-five on the adult contemporary chart, despite being banned from some country radio stations for its supposed allusion to prostitution.

The high wire Dolly was often walking was tricky. “Sex work is not simply sex,” writes journalist Melissa Gira Grant in her book Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. “It is performance, it is playing a role, demonstrating a skill, developing empathy within a set of professional boundaries. All this could be more easily recognized and respected as labor were it the labor of a nurse, a therapist, or a nanny. To insist that sex work is work is also to affirm there is a difference between a sexualized form of labor and sexuality itself.”

The question that might haunt these words and songs is, When a person makes their body into a commodity, how can they stop others from regarding it as one, and treating it as disposable? When you put yourself forward as an object, how can you control how you are consumed? Dolly carried a gun on her Times Square adventure with her friend Judy perhaps because she was so on top of this question and so many steps ahead. Sex work isn’t like any other work, because sex isn’t like anything else, but sex work is still work, and sex workers’ rights are still human rights. Which is to say, sex workers are people and not trash.

I’ve Had To Think Up A Way To Survive: On Trauma, Persistence, and Dolly Parton is out now from University of Texas Press’ American Music Series.

This article was originally published on