Culture

Larissa Pham Wants To Be Bludgeoned by Feelings

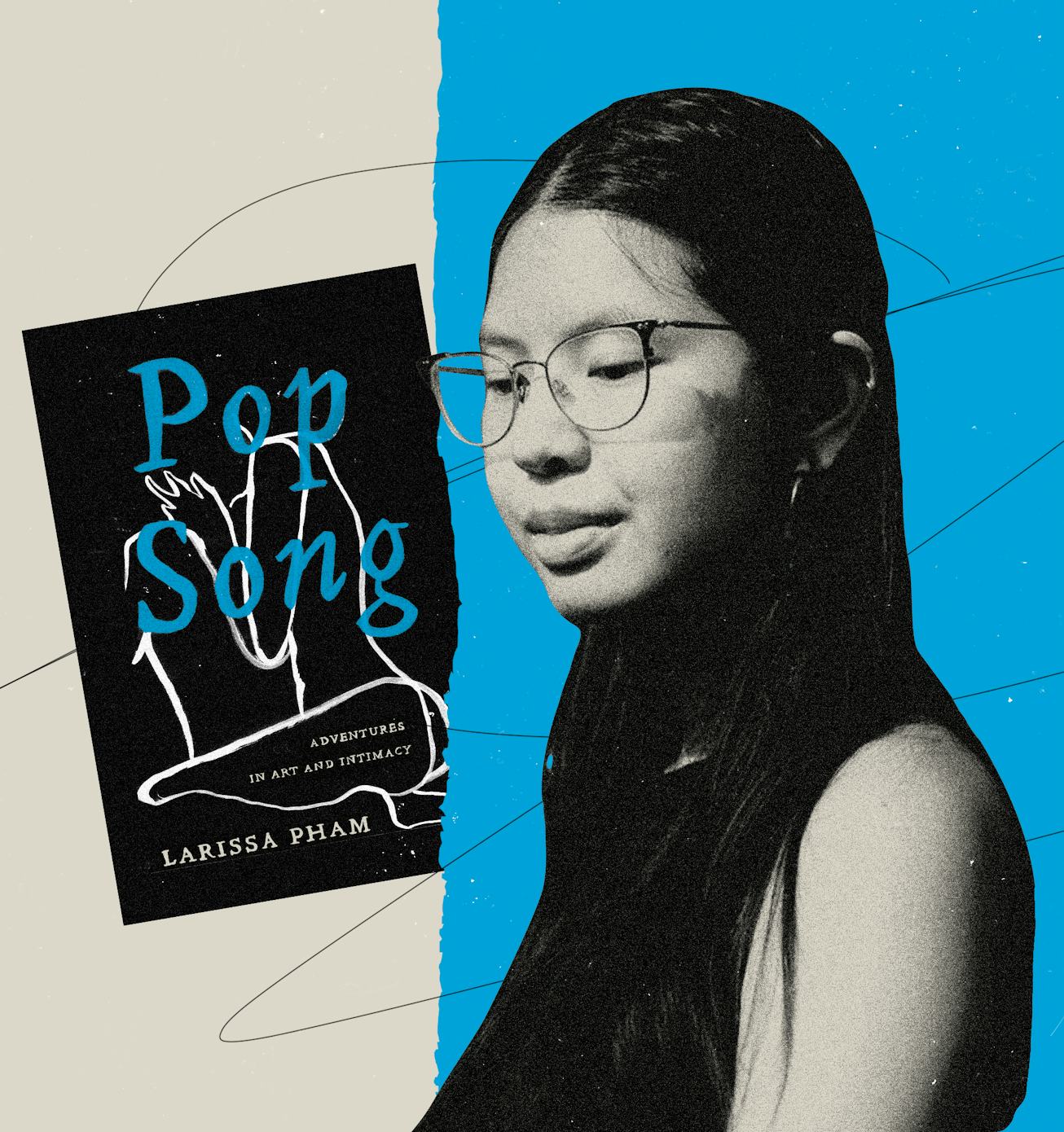

In her new book "Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy," writer Larissa Pham searches high and low for the "it factor."

Larissa Pham’s new book Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy is a masterclass in emotional vulnerability. So it’s a perfect fit that the 29-year-old visual artist-turned-essayist excitedly claims, “I really need to send Olivia Rodrigo my book!” Pham has an uncanny ability to detect intimacy, especially in art. She calls it the “it” factor: “What I mean by it,” writes Pham, an established pop culture critic who many may remember from heydays of “sad girl theory” on Tumblr, “is a kind of emotivity, a strength of gesture or performance that comes through so strongly I don’t have to know what the piece is about in order to feel what it’s trying to say to me.” Context is one thing, but if you’ve ever masochistically listened to “driver’s license” on repeat with a lump in your throat because the hurt in that song is so palpable, you may have an inkling of what Pham is after.

Sometimes, it’s a small detail. A tiny, messy fissure in a photo, song, or painting that can (in Pham’s words) obliterate us. Take the closeness to the mic, for example, on Frank Ocean’s haunting, minute-long “Good Guy.” The way it crackles, unadorned. Or the swell in James Blake’s delivery of “A Case of You” by Joni Mitchell that exists only on YouTube. Pham unpacks its magic like a surgeon with bare hands: “Blake’s voice stretches at the confines of the melody imposed upon it. It’s as if there’s simply too much of him in the performance, warping the boundary of the song, which unexpectedly grants us access into some soft passionate place that exists both in his performance and within our own hearts.”

Pham has a tattoo of the word “sensitive” above her right elbow. It is an homage to this graceful, terrifying gift. How that for Pham, even the most beautiful, ephemeral things are at risk, down to a blooming magnolia that reminds her of “little unclenching hands.” What I’m saying is: the stakes are high. When she writes head-on to a character known only as “you,” we feel Pham’s own vulnerability.

“Can I tell you something intense? I asked.

Yes, you said.

Looking back at it now it seems obvious what I was doing -- that I was trying to draw a boundary around how I felt for you, whether or not I was ready, whether or not you were, trying to inscribe it in words and make it last.”

This is the vulnerability of Pop Song that feels so reach-out-and-grabbable. “You can’t have the rewards of love without the overwhelming fear of being known,” Pham says to me casually, as if that isn’t the most devastating thing anyone has ever said. But it’s invigorating how she can express this overwhelming willingness to give oneself over to something, even if it’s dangerous, like when she says, “How often in my life, I have wanted to crest on the edge of pure sensation, seedling out the shape of something so big it could obliterate me?”

Why do we desire this? I ask, after reading a little too much into a line she attributes to a friend that goes What is the point of a crush that doesn’t destroy you? “We’re living in a pretty isolated time right now,” says Pham, having written most of Pop Song from her living room in Brooklyn immediately after New York City went into lockdown. “I think anything that can hit us with enough force to feel something that’s not alienation is appealing.”

“As for me — I see how desire could obliterate me; I stand watchfully at its edge.”

It is OK to want to feel bludgeoned by art. It’s OK to want profound, immersive experiences so big they crush us. She uses Yayoi Kusama’s art as an example, specifically an interactive installation titled “The Obliteration Room.” It begins as a painfully white room. But once Kusama invites people inside it to place colorful stickers on the walls and furniture, the room eventually turns into a violently random explosion of color and unbridled human impulse. “I know Kusama wasn’t thinking about the agony of desire when she was making these pieces about obliteration, but I find myself drawing the metaphor anyway,” she writes. “For Kusama, the fear of shattering the self leads to the desire to possess that fear. As for me — I see how desire could obliterate me; I stand watchfully at its edge.”

Pop Song pivots between art and personal narrative with such dexterity that they begin to feel inseparable. Pham writes directly of this urge to present her hurt as art and send it back into the world, waiting for some kind of validation. Here is Pham on why it felt appealing for her to take photographs of herself crying (which you’ll know, if like me, you have done this, too): “Taking the photo was my proof, but taking the photo did something else to me. It wasn’t just proof; it became performance. I chose to do this. I wiped my face. I opened the camera. I made a picture of my pain.”

But even the most confessional impulses can lack authenticity. It’s not enough to just spill your guts on Tumblr and say “here.” It takes an artistry. An urgency that Pham explains “pirouettes on the edge” while also holding back. Consider the photograph “Heart-Shaped Bruise” by the artist Nan Goldin with which Pham became so enamored that she printed out a copy of it and hung it on her studio wall to stare at as a reminder of not just what vulnerability looks like, but how it’s bound to get compressed by time and change and memory. “The photograph can’t show how the bruise will diminish, as bruises do, into black and blues. We won’t see how the burst capillaries, like lace under skin, will sour into greenish yellow and mauve. But we know the bruise will move through a rainbow of colors, mottled like the translucent surface of a plum — until finally, weeks later, and no longer shaped like a heart, it will fade back to the pink of healthy skin. We know now that the bruise has long since healed: Nan Goldin took the photograph in 1980. It is an old wound — it exists now only as a memory, a mark destined to fade, captured before it did.”

Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy is out now from Catapult Books.

This article was originally published on