Culture

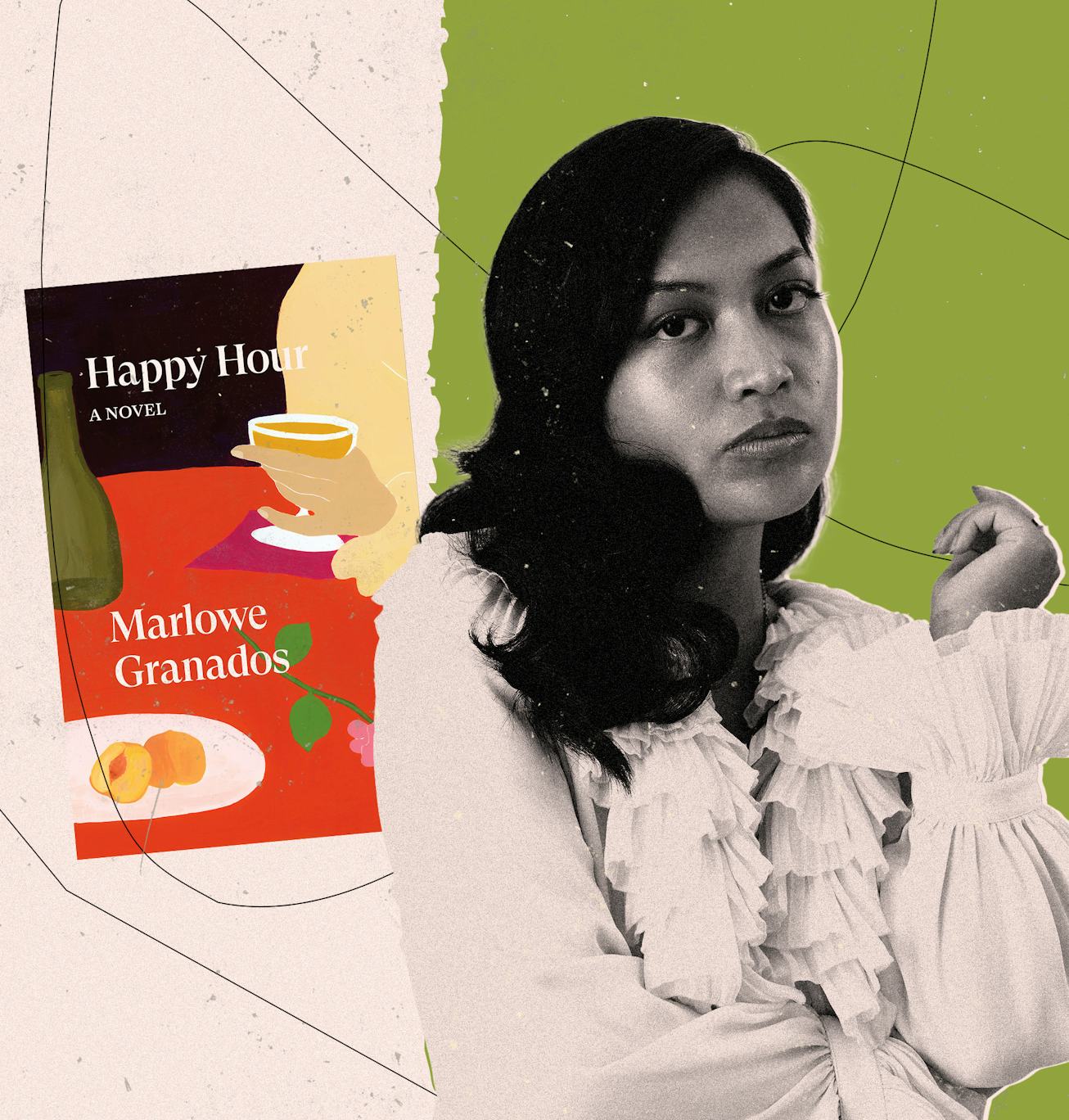

‘Happy Hour’ Is A Novel For Party Girls, By A Party Girl

Marlowe Granados’ debut novel is glamorous, insightful, and most importantly, anti-work.

In Marlowe Granados’ novel Happy Hour, 21-year-old best friends Isa and Gala move to New York City to do nothing for a summer. In a city that is all about social and economic capital, it’s a concept nobody can quite wrap their heads around, and they are constantly asked why they don’t have internships, or aren’t making art. But Isa and Gala aren’t in New York to become anything: They’re there to live and to pay attention. In one chapter, they visit a gallery show, and nobody can believe they’re not artists. But making art isn’t the point; it’s being at the opening at all: “The critic peered over his glass to take a good look at us. ‘How do you know they’re not just gathering material?’”

The novel is told from the perspective, through journal entries, of Isa, who talks like she’s in a Greta Garbo film, and who an old man would enjoy describing as a “spitfire.” Happy Hour isn’t about plot or character growth; it’s not about achieving lofty goals, but is more a series of episodes chronicling the adventures and potent social observations of Isa and Gala as they get invited to parties by friends they vaguely know, saying yes to everything from a lecture by a French economic theorist to a Hamptons trip with a British aristocrat. Happy Hour is ultimately about cheeky, frenzied frivolity and the value in living a life that’s derived from pleasure, from saying yes and trusting that living is enough.

Unlike classic New York novels, where characters move to the city to be changed by it, Granados heroines aren’t looking to be changed; they’re already forces to be reckoned with: “People think coming to New York is an answer, and that’s where they go wrong,” Isa writes. Instead of success, Isa and Gala chase glamour and experience: They share a bedroom, stay out all night, live off junk food, happy hour oysters and drinks guys buy for them, and do a series of odd jobs for cash -- they’re in the U.S. illegally -- that include everything from art modeling to being members of a live studio audience. They consider cashing in on foot modeling, but can’t afford pedicures. They seem to only ever have $5 at any given time. But that’s okay: there’s always someone to buy them drinks and cab rides home to Bed-Stuy.

Isa and Gala are young, fun, broke, and are constantly underestimated for the power they harness: that they’re able to see clearly the motivations of everyone they come across. They have a radar for spotting inauthenticity, whether it’s the friend who lives in a penthouse but “forgets” her wallet every time the check is dropped, or the man who invites Isa to the Hamptons only because he wants her to entertain his guests with her stories. “If I were to describe typical New York conversation, it would be two people waiting for their turn to talk,” Isa writes.

“Ultimately, the book is very anti-work,” says Granados. “They are very free. They’re just going around and to me that’s what New York is and should be instead of this very capitalist going, going, going all the time. It’s more about the idea of the possibility.” In person, Granados has as easy a glamor as her writing does on the page. She doesn't do formalities, casually rocks an orange eyeshadow, and you get the feeling she wouldn’t be caught dead in anything but heels. At the Public Hotel in New York City ahead of the book’s release, Granados talks about the value of frivolity, the pain and pleasure of being 21, and why saving for retirement doesn’t make sense right now. Non-party girls, take notes.

Happy Hour is out now via Verso Books.

You wrote this book between the ages of 22 and 25. But when did you start observing things that would eventually make it into the book?

I had obviously lived a very similar life for a really long time before I was even 21, but everything just started making sense to me, just like little experiences or a date that I’d be on, I just remember being like, “Oh, this is such a weird story.” I’m a storyteller with my friends, I’m always like,”‘This happened! And then this happened!” It’s always been such an oral history for me to be able to talk to my friends about stuff, so I think I’ve always had these little kernels hidden anyways, and once I figured out the voice of Isa, it would just form itself through these experiences. I put [Isa and Gala] in situations similar to ones I’ve been in or my friends have been in, and see how the world reacts to them because it’s less about how they change as people, but how the world around them reacts to them. I think that’s a really important dynamic because I think for a lot of New York novels, it's so much about how the city changes you, but Isa and Gala are such forces anyway. That line that’s like, it's an experiment for New York; it’s not an experiment for them.

Once I figured out the voice, certain things I would hear and pick up or I’d say things out loud that would be in her rhythm of speaking and it would just make sense. I think that’s really rare when you’re writing, because you have to create a specific character that you just know how they sound and it’s similar to writing a screenplay; you have to know how those characters talk in a way that’s very them. Sometimes, I’d have a thought and realize it doesn't have to be through Isa’s mind because it’s not her style to say that. So you put it in someone else's mouth and it just works that way and it builds a world that’s more believable because there’s differences between the characters are very clear.

The voice of Isa is so distinct. How did you figure that out? Where did it come from?

I obviously watch a lot of old movies. A lot of the heroines, they're very fast talking and have really good lines all the time and we don’t have that dialogue anymore because now it’s realism basically. But when you watch an old film, there’s this enigmatic way of speaking that is so in itself that art form and I just wanted to translate how that would work into a contemporary world and how that would sound. It’s funny because I think people now, especially with Tiktok, I was talking to Serena Shahidi and the way she speaks is kind of this way I had written.

I lived in London for six years, so I have this weird way of speaking anyways. But it’s this very specific rhythm and I always had to read everything out loud all the time to really make sure it sounded right and I always expect that she’s talking fast, but in a way that’s entrancing like you’re being led a little bit. Ultimately, it was very instinctual after a while. I was like, this is something she’d say; this is something she’d do; this is something she’d observe about this. It’s like something that’s possessing you. After I was writing the novel, I was like, this is so weird because now the little voice that was in the back of my head all the time is no longer there, because I don’t need to do anything with it anymore.

Totally, because you’ve put that voice down somewhere. I’m curious about the decision to make the book a diary format and have it be so fully from Isa’s perspective.

I think it was always supposed to be from her specific voice. The actual act of writing a diary is so bizarre and it takes a really particular type of person who’s going to do that and document things. First, I wrote out a monologue early on of her explaining herself, her interior life, like this is how she’d perform this speech to someone she’s meeting for the first time, what would she say to charm them. If you want to do a first person novel anyway, that’s like standard, but I wanted that additional layer of creating a document to inscribe her onto the world and have this physical proof that she exists. I think that’s important for her. She requires this final word and being able to be like, “Well, this is the only thing that will exist of this situation. Afterwards, no one else will remember; this is the final word on something.” I think that’s trying to grasp onto some type of power that a lot of times young women don’t have.

I am also wondering about the age of 21 and why you decided to make them that age? It’s interesting because they’re both enfantalized by people, but also desired. They have a certain kind of power and there’s so much at play.

It's interesting because when I was in New York when I was 21, I’m realizing now when I’ve come here recently, there’s so many young people everywhere and they’re all together, and I don't remember it being that way in New York in 2013. Even then, it was always like there were a few young people and everyone else was older and I didn’t remember lots of young people hanging out together like that. I think because [Isa and Gala] were navigating these spaces where they’re always the youngest and they’re always made to seem silly and the way people talk about young women anyways is so obnoxious. Even now, this anxiety of getting older and how ugly that makes people feel and act and write crazy things all the time about young women. I wanted to be able to show that they can be taken seriously in a certain way. They are serious about these pleasures and this pursuit of joy and having fun, but they’re also really swimming against the tide, because everyone doesn’t want that to happen. They don’t want them to laugh or do anything fun or get away with anything. I think people's fear about young women also is that they already get too much.

That's really interesting to me. People are always trying to knock them down a few pegs and it’s this bizarre thing because obviously they don’t have that much. But I think people are jealous and have this envy about youth and femininity that is often under a lot of duress. I remember reading this short essay once and there was a scene in it where the man writing it was walking by a bus stop in the morning and there were these girls going home from the night before and they were in sequins and makeup and when I read that, it was a tone of real envy that he could not have that kind of community or that kind of joy or freedom. I think that really is a specific type of dynamic that isn’t really talked about much — young women have certain freedoms but not everything — but what they do with those freedoms is very important and should be celebrated and we should commend them for that, because it's really hard to be at that age, too. You don't have any career opportunities; you don’t know what to do; you’re just sitting there like, “What do I do?” So you have fun. It doesn't matter as much at 21. It’s interesting, in Canada and London the drinking age is 18, 19 and it’s so weird to me here that it’s like unless you get snuck in — which, I always got snuck in — that’s the first year of being able to mingle with real adults and that’s really an interesting dynamic to be the lowest rung.

I remember turning 21 and being like, “Oh there's this whole world I can enter now that didn’t exist for me before that has all of its own customs and people and you don’t know how to do anything.

Yeah, you’re still kind of learning and what happens with them, they’re rubbing shoulders with people in the upper classes and they don’t know what to do, especially with Isa trying to be tactful, but it’s like not coming across properly, or people are against her anyway; it doesn’t matter what she does. I also just didn’t see anything that was showing my life in media. It was such a clear gap for me because obviously all my girlfriends live like this and it seems weird that it’s we're not talking about it, and the funniest thing, too, is that I feel like my friends think about writing in such a particular way. They think it’s weird that I wrote about this, they’re like, “It’s so normal. Why would you waste time doing that?” It’s so weird.

It is so normal and when I think of “party novels,” if there are young people partying in an novel, something really bad happens, or someone gets addicted to something and the story is that they learned to not party and reform, instead of being like, “This is fun and messy and there's value in that.”

What that misses is a lot of us grow out of those phases and move into other ones, and it’s fine. I don’t like the idea of them having to go through all these consequences to learn something; that is just not how life works. When people were first reading it a while ago when we were first pitching it, people didn’t understand. It’s not a classic structure of a novel. New York Magazine called it a “picturesque,” which is what I call it, too. It’s literally a series of adventures and I always wanted the book to seem like you're in a large house and each room is different and you’re going through each room and exploring all these rooms. We don’t have these kinds of young women adventurers anywhere and they are like that. They always say yes to everything and they're like, “Why not?” and it doesn't occur to them to say no. I'm still like that.

“They are serious about these pleasures and this pursuit of joy and having fun, but they’re also really swimming against the tide, because everyone doesn’t want that to happen. They don’t want them to laugh or do anything fun or get away with anything. I think people's fear about young women also is that they already get too much.”

I’m like that, too. I love that they’re uninhibited and there doesn’t have to be consequences — because they're not doing anything bad and people have a hard time seeing that.

Yeah, theres not like a pregnancy and abortion scene. There is a line about Isa getting an abortion, but it’s very glossed, like, “This happened and it was like a punishment for me and it’s whatever. I can’t deal with it, it’s whatever.”

Yeah, or when Gala gets bit by the dog, that's like the worst thing that happens.

Yeah, possibly getting rabies.

But then there is also an underlying economic precarity. There's not a safety net. Gala and Isa are getting things from people who have money. We think of the idea of a “grifter” as a bad thing, but it’s out of necessity.

Yeah, and if you think about it, the easiest thing a young woman can get is drinks and dinner. They're not going to get stocks and bonds. I think about women in the 20th century all the time and before, when you were dating someone, they'd give you a fur coat or jewelry and that rarely happens now. It’s not a thing and sure, a dress sometimes here and there, but not a mink coat. And the thing about the mink coat was that it's such a beautiful object for them to have, but also if they needed to they could sell it and that’s literally having security. Now, it’s not so different. When you think about the classic gold digger trying to get diamonds and stuff; diamonds are not a thing anymore, they actually lose value a lot of the time. I think about that a lot. Even now, I know sugar babies often get gifted purses, but they often resell it and I think that's such a good one, but still they're not retaining the value of it, so they’re always losing in some way.

Right, Isa and Gala are always losing, but that's why this book is so good, too, because they also have so much power because they are able to clearly see the motivations of everyone.

They don't get stressed. And the idea is that money is always coming and going, and I think that’s a necessary way to look at your life now, because obviously there are catastrophes happening and I think it's so crazy when people think about their lives in terms of saving for retirement. I’m like, “What do you mean?” That’s such a bizarre inclination now, so I think there’s going to be a shift in terms of how people spend money and obviously there’s always been people who are hand to mouth, but I think there is going to be a very pleasure-based economy where people are going to want to do things they probably won’t get to do later because something might be underwater.

Right and obviously you wrote this years ago, but that idea feels very post-lockdown. This summer, it feels like people are indulging in a lot more of these easy pleasures and going out and seeing the value in things that are frivolous.

I’m always really interested in the idea that frivolity is so feminine, too. When we think about men, their version of it is escape, this kind of very particular type of adventure for them, whereas frivolity is the pejorative.

Adventure is productive for their lives because it enables them to blow off some steam; whereas for women, it’s just silly.

Right, it’s like, “Oh, you’re getting your nails done?”

You feel like you have to justify it, when it’s like, we don’t have a lot of time, so why not?

When you want to be a lady of leisure or whatever, it's fine to take lunch and have a martini. People don’t want to stop. One of the things I try to think about in the novel, and I’ve always thought about it in the way I feel about New York, is there’s a kind of ambition that lends itself to going, going, going all the time, and I am not like that at all. I find it very bizarre to live like that and ultimately the book is very anti-work.

No one can believe Gala and Isa are in New York aren’t doing anything, but the twist is kind of that they are, because they’re observing, which is actually more helpful for your life.

Totally. The way they are intelligent socially is a huge skill that I think we often don’t really think of. They navigate these scenes and can spot inauthenticity in such a particular way and it's funny, because even those people who are inauthentic, but their whole pursuit is trying to be authentic, when they see these girls, they roll their eyes at them, even though these girls are truly the real thing. They are very free; they’re just going around and to me that’s what New York is and should be instead of this very capitalist going, going, going all the time. It’s more about the idea of the possibility and it's still true now. You can be in a dive bar and a penthouse in one night and that’s kind of the fun and for me that’s why anyone would want to spend time in New York.

Right, like the possibility of the night.

And even if it's bad — you always have the next night.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on