Culture

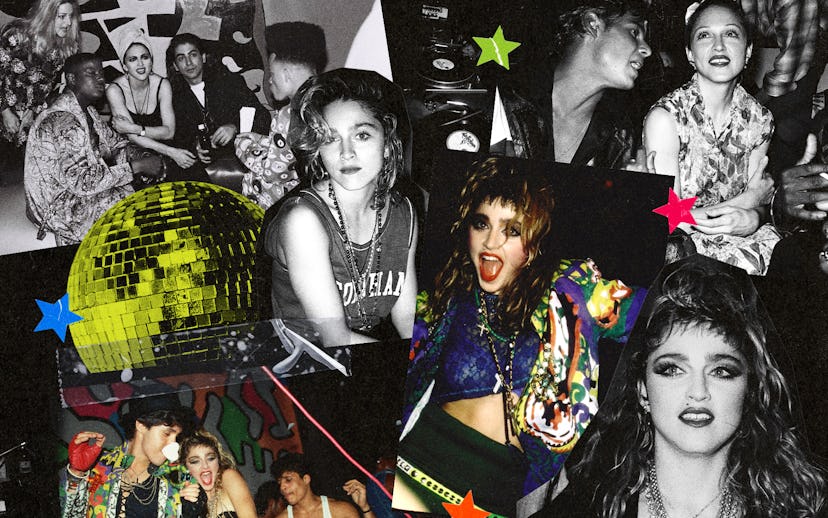

The Clubs That Raised Madonna

The sights, the sounds, and the birth of Madonna.

Madonna’s New York City mythology begins in 1978 with a taxi arriving in Times Square. The 19-year-old steps out into the city that would define her, and her it, fresh off of her first ever plane ride from suburban Detroit, allegedly with $35 in her pocket. “It did not welcome me with open arms,” she writes in a 2013 essay detailing the multiple robberies and assaults she experienced in only her first year. If the city was unwelcoming, the nightlife was not. Like many nonconformists struggling for their art, Madonna found community and created opportunity in the expansive city club scene. It was the right time and the right place, with nightlife that could never exist today. Sprawling underground megaclubs filled to capacity each night with fashion, art, and music avant-garde scenes. Madonna is a descendent of these verging artists taking influence from one another on the dancefloor, creating the culture that would soon consume the world, in the sacred spaces that would house them well past dawn.

Beginning in the late ’70s, the Warhol-led scene from Studio 54 would make its way downtown to the Mudd Club, a TriBeCa loft space that drew artists like Blondie, The B-52’s, and The Talking Heads to perform for a variety of now-legends like Alan Ginsberg and Betsey Johnson. In these early days, Madonna was still performing with bands The Breakfast Club and Emmy and the Emmys. The Mudd Club scene drew an A-list crowd that craved downtown’s punk cutting edge. It soon merged with the younger, scrappier DIY scene at Club 57 on St. Mark’s Place, bringing Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Madonna’s eventual boyfriend. She became a regular at both clubs, mingling at parties ripe with shock value, meeting the artists she would share space with for years to come. DJs’ selections were as eclectic as the crowd who came to 77 White St. to escape the ostentation at Studio 54 and soak in the ultimate art culture melting pot before both clubs closed in 1983.

In 1981, Jellybean Benitez became the resident DJ at The Fun House. The club had been adhering to the standard 4 a.m. closing time, sending hundreds of sweaty dancers out onto W 26th Street. As The Fun House grew, the party would go until noon on Sundays, with Benitez playing 14-hour sets. The crowd was young, drenched in underground music culture, and serious about dancing. It was in this regular mix of nearly 3,000 people at the club’s peak that the Bronx-born Benitez met Madonna, his soon-to-be fiance. His sets were eclectic, with early electronic, underground disco, and freestyle, the Bronx’s answer to over-played disco. The only breaks he got were for performances by bands like England’s New Order, who filmed the video for “Confusion” to a weekend morning crowd, and took inspiration from the club when opening Hacienda in Manchester, as immortalized in the 2002 film 24 Hour Party People.

While all of this transpired, Madonna was a fixture on the dance floor, and behind her boyfriend’s DJ booth, finding influence in freestyle for her own music that would soon become Fun House anthems. After Benitez produced and remixed several tracks on her 1983 debut album, including “Holiday,” he shared them with DJ friends like Larry Levan at Paradise Garage; before the album even came out, the tracks erupted in the subversive scene, with clubgoers eager to champion one of their own. The couple stayed together, but with the release of the “Borderline” video and Benitez producing for artists like Whitney Houston, fame intervened. Their relationship shifted and ultimately ended in 1985, the same year that the Fun House closed its doors.

During these years, starting in 1982, Madonna was likely making her way a few streets down, still between Fifth and Sixth avenues, to 21st Street where the second iteration of Danceteria was becoming legendary. It may not have set out to be the punk, anti-Studio 54, but it was brimming with creative energy, and those on the cutting edge of their craft were at the top of the social hierarchy, not uptown celebrity VIPs. It was also the perfect “day” job for pre-fame stars: Debi Mazar worked the elevator with LL Cool J; Sade was making drinks behind the bar where Keith Haring was a busboy, along with nightlife omen Michael Alig. When Madonna wasn’t waitressing or on the dancefloor, she was at the DJ booth where she first met resident DJ Mark Kamins, who helped her secure her first record deal at Sire Records — and also became her boyfriend. In addition to a rooftop, the massive four-floor venue had DJs on the first floor, a full performance space on the second, and on the third, a restaurant and the first ever video lounge, a new multimedia concept that would soon take off.

RuPaul and Vivienne Westwood would hang; Grace Jones, The Smiths, and Whodini would perform. Genres and scenes melted and mixed like no other place in the city. It was at Danceteria that Madonna cemented herself as an artist among the high tier fashion, art, and music crowds, persuading Kamins to play her newly recorded debut single, “Everybody,” and giving the first live performance of her solo career on the second floor stage. Fate continued to serve her at the club as she starred in the 1985 film Desperately Seeking Susan. During an iconic disco scene filmed at Danceteria, production needed a track for the dancing background actors. Madonna pushed for a cassette she had on hand to be used, her latest demo “Into the Groove.” A new track by Kamins and rising star Cheyne was set to be edited over the scene, but after watching the actors with Madonna’s new hit, editors ultimately kept “Into the Groove” for the film’s final cut.

1986 brought the end of this historic location, while Danceteria’s Hamptons outpost continued. A third Manhattan incarnation ran from 1990 to 1993 on E 30th Street but never reached the heights of its former glory. When giving names to the coveted standing room sections of her forthcoming Celebration Tour, Madonna paid tribute, naming General Admission Pit 1 after the club that gave her the first stage. As for Pit 2, she exalted another crucial influential space, the Sound Factory.

By 1989, Madonna had released four studio albums. “Like a Prayer” was causing controversy, and while her music had reached the mainstream, she remained steeped in the subculture that brought her to a converted warehouse space at 530 W 27th St. The ostensibly gay Sound Factory drew beyond the beefy Chelsea demographic, bringing the “bridge and tunnel” crowd, “suits,” yuppies, most there for one particular DJ: Junior Vasquez. An honorary member of the House of Xtravaganza, Vasquez could be considered single-handedly responsible for introducing voguing culture to the masses, particularly to his close friend Madonna. The scene had rarely left their Harlem ballrooms and stunned the Sound Factory crowd with early Sunday morning performances on the club’s provisional runway.

Without the sale of alcohol, the club skirted the 4 a.m. closing laws, and shows would commence at 8 a.m., continuing into the afternoon. Galvanized, Madonna wrote her 1990 hit “Vogue,” allegedly recorded in a basement in Midtown, and cemented voguing into mainstream culture. Vasquez has compared their close friendship to that of siblings. It was possessive, particularly between Madonna and her rival Cyndi Lauper, and created a fiery collaboration that lasted until 1996 when he released the track “If Madonna Calls,” featuring a voicemail she had left him, without her permission. Seen as a campy diss track, the two fell out and have not spoken since. The Sound Factory closed its doors in 1994. Toward the later years, the fame of the club and of Vasquez himself took focus from the music and the fierce commitment to dancing the Sound Factory was founded upon.

Blame Giuliani’s insistence that the city be “clean,” or the industry’s evolution favoring $400 bottle service over live performance or avant-garde DJs, but the Manhattan nightlife that birthed these clubs has vanished. Eras come to an end, but traces of their legacy can always be found, inspiring new venues, new artists, and when we’re lucky, new work from someone who was actually there.