Culture

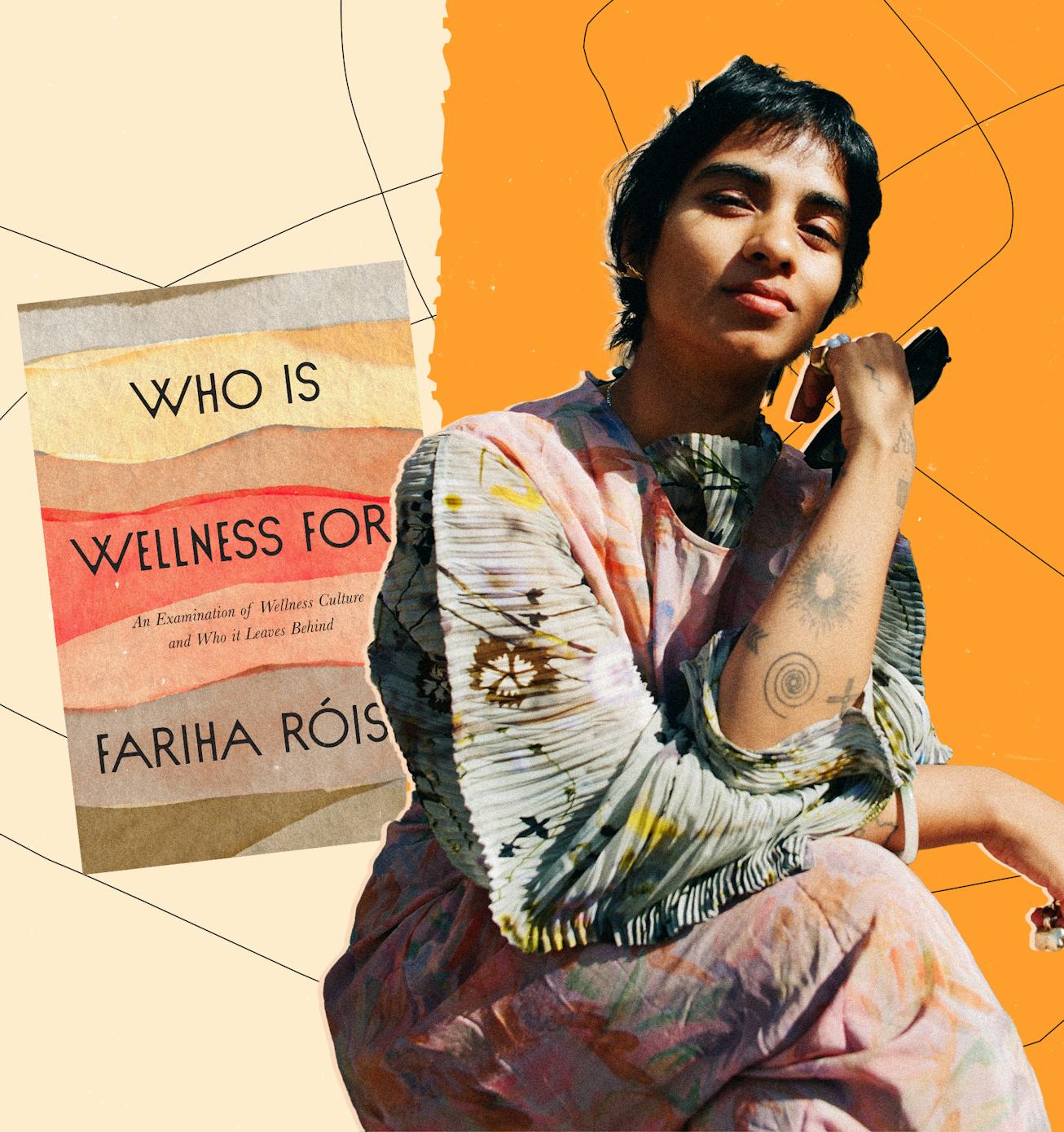

Fariha Róisín’s New Book Questions The Appropriation Of Self-Care

In Who Is Wellness For? author Fariha Róisín examines the booming and white-washed wellness industry — and who is left out of the healing.

The body keeps the score — the record of every trauma that’s been inflicted on it. From the way we clench our jaws out of stress to the way anxiety stores itself in our gut and manifests into different ailments, Australian-Canadian writer Fariha Róisín knows this all too well. After surviving abusive relationships in both childhood and adulthood, Róisín intimately knew the ways trauma had made a home for itself inside her body, and the various illnesses that were beginning to form in response to it.

It was through her healing journey, however, that Róisín was retriggered by the wellness industry. She witnessed the capitalist co-option of Audre Lorde’s initially revolutionary concept of “self-care” to the way that practices like yoga have been turned into a booming industry fully divorced from its Hindu origins. In her latest book Who Is Wellness For? Róisín investigates and interrogates the dual trauma of being a brown queer person with a body in emotional recovery to the trauma of navigate a wellness industry that’s appropriated, white-washed, and commercialized many non-western practices and medicine.

Ahead, NYLON spoke with Róisín about her book, the journey of coming to terms with not only her body, the industries that prey on people’s desire to heal, and more.

What was the catalyst for writing this book?

I needed this book. I needed this book to be in existence. I wasn’t sure if I was the person who was gonna write this book. It was something that I always felt like, as soon as I started investigating wellness and self-care, even for myself back in 2014. I started to sort to change direction from film criticism and culture criticism more to just thinking about wellness and really paying homage to the work of Audre Lorde and bell hooks and the kind of archival work that they did in the ’70s about self-care, and sort of thinking a lot more expansively about how to look after yourself. That to me was really interesting.

And then the more I started to do that kind of investigation for myself, I began to realize that there was an entire world of information that I never comprehended. And that was sort of my own ancestral lineage and cultural lineage was very much like rooted in that reality and rooted in the wellness world and nobody was talking about it. It was something that I felt necessary and I think that’s how this book kind of revealed itself, and then became something that I wrote.

What has been your own relationship with the wellness industry? When did you realize it was not as hospitable as it portrays itself to be?

I think when it really started to conflate itself with capitalism and I think that was sort of 2015, 2016. Things like the language around it like “treat yourself” and “self-care,” there was this kind of like a joke that started to arise, and the way that the market began to co-opt that language of caring for yourself. That’s when I started to be like, “Hang on, there’s something here that does not feel good.”

I was always concerned because I worked at a yoga studio for a while. I volunteered because I could not afford a pass. I worked at a white-owned yoga studio in Montreal for a couple of years and just witnessing and realizing that I personally did not feel good about white women saying “namaste” in front of me when there was no other South Asian person in the class. It just felt really off. If you’re only doing yoga and meditation and these spaces are only for white people, but it’s co-opting the language and the culture of something they don’t primarily understand because they’re not even contextualizing it. That to me was really concerning. And so the more I sort of just sat with it and the more I became radicalized in my own language and radicalized in my own understanding of the world, the older I got the more I was like, “I can say something about this. My work doesn’t need to comply. I don’t need to comply and my work doesn’t need to comply.”

And besides bell hooks and Audre Lorde, was there anybody you saw writing about self-care and wellness and the capital co-option of it?

No, not since them. I mean June Jordan, also. There is I think really interesting writing about death, for example. Like death is something I really think about a lot. I want to be a death doula, I’m sort of training for that. It’s something that I think that goes hand in hand with thinking about disease and illness, and therefore wellness. But not really. I think there are interesting offshoots, but especially now there’s nothing like, “Okay, capitalism is very much entrenched in wellness, how do we actually talk about this? How do we actually not only acknowledge, but how do we stop this? This is wrong. This is not good.” That is very much what the book lands on for me, this belief and hope in revolution and truly wanting to be like, here’s a book that hopefully will allow people to understand that these things are not okay. I’m not telling people to stop practicing yoga obviously, but it’s more like have the context, know what you’re doing, and care.

Can you talk a bit about what brought you to wanting to be a death doula?

I think as a child sexual abuse survivor, I have always been on the precipe of death. My body was taken from me at a very young age. I’ve been trying to process that for the last twenty-five years or more. And it’s sort of just like a personal interest of mine, but when I first heard about it I think in 2017, 2018, that was the first time I met someone that was training to be a death doula and my body – there was something electric in it. I realize I sit with sacred medicines a lot, I sit with Grandmother Ayahuasca a lot. I’m sitting again tomorrow in ceremony, something I’ve committed my life to. And that kind of commitment is something I’m drawn to.

I want to understand why we’re here. I want to understand how to live. I also understand the profundity of living your life to the fullest is living and accepting death. So for me those two things – life and death – go hand in hand. I’m Muslim, it’s sort of in my lineage. There’s a lot of emphasis on dying in Islam and there’s just a lot of death remembrance. I write about it in the book, it’s this core of a lot of eastern faiths, the idea that you have to die in order to gain the most from this life.

You write a lot about being abused by your mother and by a former partner in this book. What was something that was particularly hard to write?

The hardest part is that it’s true. The hardest part is that that’s my reality. It was really tough to write it and reread it and reread it and reread it and be like “Why did I have such a f*cked up life?” It’s tough but I think the humbling part of it is that I hope and pray that it becomes a template for other people who’ve experienced this level of abuse. Especially parental abuse, especially incest. And they can begin to sort of love themselves, that’s really sort of my corny hope for people. Through the journey of writing this book I taught primarily other child sexual abuse survivors and that was incredibly humbling for me because I was like, “I’m not alone and there’s so many of us.” And that also made me realize that this book is really important for those people in particular.

There’s so much language you don’t have when you’ve been harmed at that level, or when you’ve experienced domestic abuse, or any kind of sexual abuse that has traumatized you. It kind of leaves you in a state of feeling and wondering if whether or not you’ll ever be good. Whether or not you’ll ever have normalcy. There was so much of my life where I was like, “Will I ever be normal? Will I ever have love?” I’m finally at this stage of my life where I’m like, “I am loveable.” But that work is so big and that work means you have to sort of reframe and rewrite and rewire so many things in your brain about your worth. And when that worth is stripped from you because of a partner or because of a parent, it’s very hard to engineer yourself to trust and believe that you are loveable.

“I want to understand why we’re here. I want to understand how to live. I also understand the profundity of living your life to the fullest is living and accepting death.”

Did you practice any sort of aftercare during the moments that felt triggering?

I’m lucky because I’ve been in these worlds for so long that now I have a trauma therapist and I do acupuncture once a week. I know how to take care of myself. But I think the scary thing about doing this work is that it’s lonely. It’s deeply lonely. And you don’t know who to lean on and sometimes you don’t really have someone to lean on. But the aftercare was also trying to find joy where I could. As much as I could.

And what brings you joy these days?

Connection. Like real connection with people. Honesty with people. Not performativity. Just being real. Films, movies, music, food. Investing in laughter, watching a lot of stand up. Watching a lot of comedy. Reading. Beautiful objects. Learning how to take care of myself. Learning how to love myself in a genuine way, not just for my productivity. Genuinely being like, “Fa you’re a good person.” I think investing in being a good person has really changed my life because it’s the only way I move now. And that brings me a lot of joy and it’s a consideration I move with every day. No matter how someone treats me, I want to be kind, and that has brought me a lot of joy.

What did you learn about yourself through writing the book?

That I’m a warrior. I’m really ready to fight. I really care. And that really did something to me. Something shifted in me as I wrote this book, especially because I wrote it during the pandemic – we are not okay. We are not okay as a society. It is not okay that white rich people can just detach and go somewhere and just be like, “Oh I’m fine.” That to me is not okay. And I felt this fire emerge that I think had been dormant for a while. Because when I was a kid, and I kind of talk about this in the book as well, I was deeply political. I started this social justice group in my school. I was a part of Model UN as a child and the first thing I wanted to be was a human rights lawyer, that’s what I went to school for. And then I was deeply demoralized by the experience of working at the United Nations. I did an internship when I was eighteen. I completely just detached from that world. Like nothing matters, nothing’s going to change.

And for most of my twenties, I kind of felt like that. I felt like, “Well, maybe all you can do is care about yourself.” Obviously I never went into becoming an asshole, but I definitely felt that. I definitely thought “OK, maybe I just have to care for myself and be selfish.” And then when I wrote this book and as I wrote this book, I sort of brought back that teen version of myself, and it just really radicalized me again.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on