Entertainment

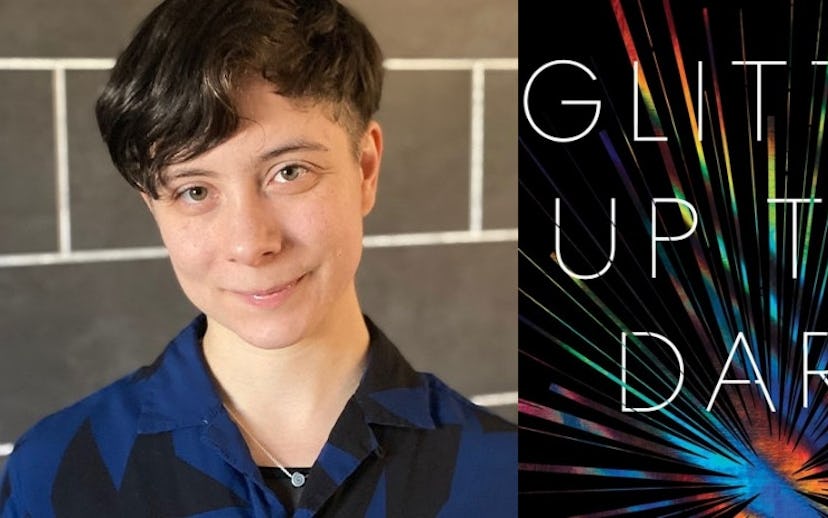

Sasha Geffen's 'Glitter Up The Dark' Unravels Queer Music History

The Colorado-based author and music critic's new book makes the case that pop music has always been queer

More than any other art form, music is what brings people into their bodies. The vitality of sound pulsates through fingertips and eardrums, deep into the nervous system bringing life wherever it travels. For queer people, it often goes deeper. In a world that has perpetually denied some people's innermost desires, the ability to create and consume music that fosters identification with others can be a lifeline in otherwise inhospitable conditions. A dynamic relationship is formed each time a record is put on in a sweaty club, its participants ready to become themselves once more.

Understanding the new forms of queer identification that emerge through music is one of the main themes of influential critic Sasha Geffen's new book, Glitter Up the Dark: How Pop Music Broke the Binary. Geffen, who explores the relationships between gender identity, vocal performance, and technology, asserts in the book's introduction: "Queer desire pulls together like elements, finding attraction in affinity." It's this affinity Geffen finds between ear and sound, fan and performer, from generation to generation that connects the musicians highlighted in their book.

Without attempting a comprehensive overview of queerness in music, Glitter Up the Dark nevertheless traces a clear path from the Beatles onwards, largely informed by Geffen's own taste and their interest in the voice as a defining site for gender dissonance. Whether it's the time-shifting energy of '70s New York clubs like the Loft, the "sapphic androgyny" of Prince, or the gay masculine identification channeled through Grace Jones's "I Need A Man," Geffen makes clear that performers and their listeners have always been engaged in a lively, flirtatious exchange, constructing vibrant, expressive, and more fluid worlds in the space between each reverberating sound wave.

On a recent morning early into quarantine, NYLON spoke to Geffen about the role the voice plays in creating space for gender weirdness, the erotic exchange between listener and performer, and the state of queer music in the age of streaming.

In your book you write, "When it hits the ear, the voice conveys information about the body from which it issues." What is the information you're paying attention to?

Pop music, even in its most expansive sense, is not that different from itself. There are a pretty limited set of configurations that appeal on a pop level. So structurally you're working with a pretty limited framework, but the texture of the instrumentation and especially the texture of the voice in its malleable permutations is where I think the most interesting things can happen. The way that the voice can stretch or break or sustain itself, both organically, in the body and the throat, and also through processing, is something I'm really interested in, especially when it comes to trans artists who are using it in provocative and fun ways.

The voice is a very common communicative tool. When someone is singing or speaking, you can feel that correspondence in what it feels like for you to sing or speak, and I think that's kind of why the voice has opened up so much space, especially for gender-weird people. Because when we hear someone using a voice against what is expected of it, it can open up space in our own bodies to start to push against the expectations that we feel all around us.

Queer liberation doesn't look like Target profiting from gay anthems!

That sense of gender-weirdness you describe is something that often connects musicians and listeners, especially as they seek an escape from heteronormativity. Particularly as it relates to the voice and how it can help foster identification in unlikely ways, how do you see music doing that kind of connecting?

Something that's always interested me is where falsetto comes in. For an artist like Sylvester, he used falsetto to occupy the same space as someone like Patti Labelle, using the same melodic range as some of the women that gave rise to disco. It's cool to see that trajectory happen in the span of a decade. Disco starts in the early '70s, and by the end of the '70s you actually have these androgynous gay men making music that forms the basis of identification from several years earlier. I think Sylvester is such a fantastic example of that: it's such a gay voice, and working with Patrick Cowley, who was a gay producer, you can get a little bit more anxiety in the beat, like a little bit more energy than you got from Giorgio Moroder, who was just kind of being straight male-y the whole time.

That phenomenon of finding identification with the gender that you feel has exploded more recently, just because we all have much wider access to music than maybe we did before on account of platform capitalism and the streaming economy, for better or worse. All of this stuff is much more available than it was before. You kind of see that in microcosm with disco, going from something that was this symbiotic relationship between DJs and divas, music being played in clubs that summoned the feminine and outrageous and excessive voices of female divas that inspired identification and movement and sex for the gay people who were attending these dances. It's like a very erotic exchange, this very sensual experience, and that moves into gay men actually making their own music that sounds like those divas. Sylvester's voice is pretty much a diva voice, which I love. There's this loop of identification that just keeps building, and I think is still happening now.

You talk about more recent artists, including SOPHIE, Arca, Perfume Genius, and Yves Tumor, utilizing this loop of identification. What does that look like in music culture today?

What I see as the most pressing question is how we deal with this crisis of capitalism, and how visibility is being turned against in a lot of ways. Something that comes to mind is Sam Smith's recent cover of "I Feel Love" by Donna Summer. You have this song that inspired tons of queer identification in the 1970s when it came out, and in the years since, directly led to the formation of house and techno as genres. It's this hugely influential and liberating song, and then in the 21st century, almost 45 years later, you have an artist who's trans covering it, using their incredible falsetto, for a Target ad for their Black Friday commercial. All of this liberatory potential is being subverted into this incredibly capitalistic force, right? Hearing it on TV just kind of depleted that cover of any potential it might have for me.

A lot of trans and queer artists are very visible and are profiting from their visibility, and they're also using their visibility against broader liberation. Queer liberation doesn't look like Target profiting from gay anthems! But I also see artists who are maybe a little more experimental and fringe-y still working within capitalism, making music that can be appropriated for capitalist ends, but getting resources for themselves so that they can redistribute it in some way, or at least just keep themselves alive.

I think of the most recent Arca release [@@@@@]. It's difficult to decipher literally, like it's hard to hear what she's singing with all the vocal effects. But it's also, as a 62-minute track, indecipherable to a platform like Spotify, this giant, blood-sucking entity that's profiting off of music without giving much back to the artists themselves. It jams that system because it's not something you can really add to a playlist of popular new releases. To jam that system with the mechanics of your music, I think is a very interesting and vital move right now.

Being able to glitch things where they most need to glitch while still remaining recognizable, especially for other trans people, that that's a strategy that I see getting deployed again and again. I think it was something that SOPHIE was doing with her early work – maybe not intentionally, but certainly effectively. She was making music that sounded very strange to a lot of cis people and very much like home to a lot of trans people. I guess the question becomes, like, how do we communicate with each other in ways that are really vital and necessary for our survival, while not falling into the trap of wider visibility?

Glitter Up The Dark: How Pop Music Broke the Binary is out now via UT Press.