Entertainment

How To Make "Thoughts And Prayers" Meaningful

Alissa Quart talks with us about the "dark poetry" of American politics

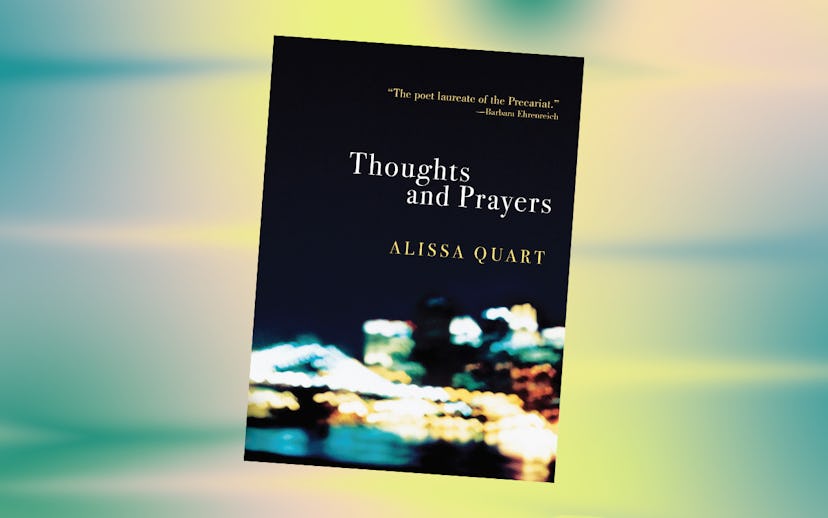

As I wait to meet Alissa Quart in the lobby of the Norwood Club in Chelsea, "Thoughts and Prayers," the 2018 single from jazz singer Ann Hampton Callaway starts playing over the sound system. It's one of those stranger-than-fiction coincidences, considering Quart's newly released collection of poetry also shares the charged platitude as its title.

Through her work as both a writer and the executive editor of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, Quart is all about clueing people into what she calls the "dark poetry around them." Thoughts and Prayersis no exception, dexterously speaking to the calamity and melodrama of our current political climate using the hybrid form of reported poetry. "I see this as a meta-text, a text around the journalism," says Quart, a prolific journalist who has also written several nonfiction books on topics such as consumer culture and middle class precarity. "Sometimes journalism gets locked into the literal truth," she says. "Potentially, a form like poetry or other kinds of more explosive, disruptive forms of culture could be telling the emotional truth of our period, especially the Trump era."

"'Thoughts and prayers' became the most empty phrase, but then it became almost the most full phrase, in the sense that it was like a sign or a signifier of hypocrisy, avoidance, pseudo-religion," says Quart. "I feel like you could go out the other side and almost reclaim it, where you're like, 'All poems are thoughts and prayers.'" This type of reclamation and recontextualization are Quart's speciality as a poet; the phrase in question also lends itself to a poem in the collection, composed using language from different politicians' public statements about recent mass gun violence, reworked with chilling mastery.

Having reported extensively on abortion rights while working with Maisie Crow on the award-winning documentaries The Last Clinic (2013) and Jackson (2016), Quart filtered dozens of interviews with women she spoke with for the projects into the poem "Clinic." The resulting piece is a poignant nine-part tableau that blurs the lines between verse and reportage. "I think, for me, there's a lot of affect that accrues when I report that doesn't necessarily fit into journalism, and that's where the poems come from," says Quart. "Like all the feelings I had when I was in those clinics—you want to be hyper-rational and even-handed and all these things, but in the poem I don't have to be that. I can also have emotional reporting, [which] is what I sometimes call it."

As a child, Quart was a gifted poet; in 1989 at the age of 17, she won a national contest and wore an ACT UP button to read at the Bush White House. She pursued a career in journalism in part for practical, financial reasons, but is acutely aware of the ways the seemingly divergent forms of hard news writing and poetry can be complementary. "I felt like a poem could still be reported and accurate and fact-checkable, but it could get at the matrix of meanings in a different kind of way," she says.

Though considered by many to be subjective by definition, poetry today is more necessary than ever in capturing the multiplicities of truth in our modern news cycle. When the New York Times Magazine appointed former U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove poetry editor in 2018 and started running poems she selected alongside hard news on a weekly basis, Dove told Columbia Journalism Review that she considers poets to be "modern-day griots," positing poetry as an exercise in perspective for an increasingly polarized culture. "You tell the story, but you tell the story that's under the story. You bring to light human reactions to grander events, in the hope that people will recognize themselves in it," said Dove.

At the core of Quart's poetry, for all its whirring machinery and institutional antagonism, is the human element; the depiction of "Women afraid of dying while/ they are trying to find their life" in "Clinic," for instance, is especially heartrending given its basis in real life. Quart credits her journalistic training with helping her strike an ever-tricky balance here: crafting her real subjects' stories into a truthful work of art without ever coming across as voyeuristic or objectifying. "I think my professional deformation does me a favor in the sense that, if I'm doing this, it has to be accurate and as empathetic as possible," she says. "If I'm going to doctor it in any way, it will have the sort of values or codes of journalism; I'm imposing them on poetry."

The collection features an epigraph from the late poet John Ashbery: "But the past is already here, and you are nursing some private project." In considering a fraught present and precarious future, Quart often revisits the past, like in "Apocalypse Anyway," which catalogues the bygone pre-Y2K era "When people murmured into pay phones about their mental lives, when they fucked on the phone." The "dirty nostalgia" of the poem pervades throughout Thoughts and Prayers. "The private project can relieve some of the pressures of the past, help us find the past in the future, help us get rid of the past, maybe," says Quart, "But a lot of us after the Trump election escaped into quietism, which is tending our own gardens. If we get too private, we're gonna be damned in some way."

Another poem in the collection, "The Harasser's Apology," is assembled from the public statements of prominent men who have been accused of assault, such as Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey and Donald Trump. It's a biting cacophony of non-remorse: "I am sorry for the feelings/ he describes having carried," reads one stanza. "I'd be reading these apologies and I'd be like, 'I want to cut them up, I want to juxtapose them to show the repetition, the emptiness, the moments of surprise in them and the moments of rhetorical similarity,'" says Quart.

This is that "dark poetry," the twisted rhetoric of our current political landscape that can either be taken at face value or flipped and refigured into something potentially radical, complete with new forms for our new normal. Quart cites the "lyrical possibilities" of social media as especially interesting, and refers to a Twitter thread started by the U.S. Army which unintentionally garnered thousands of harrowing responses describing the widespread trauma endured by veterans and service members. "Every single one was like the most tragic novel you could imagine," says Quart, who actually used the thread to recruit writers through the Economic Hardship Reporting Project to tell their stories.

As for her own writing, Quart is continually returning to the form she considers vital. "I can't help myself, like I was just on a plane and I wrote two poems. It's almost like knitting, or something," she says. "I mean, that sounds terrible, but like, I need it."