Entertainment

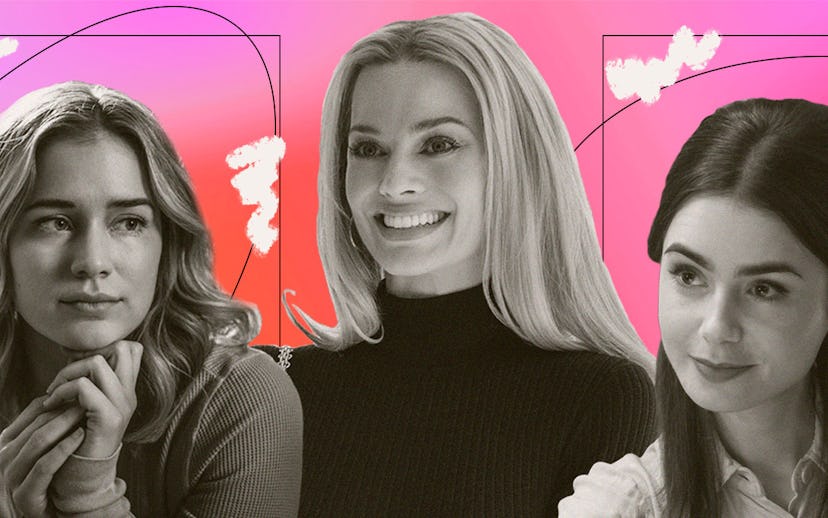

When Will Women Get A Break From Hollywood’s Serial Killer Obsession?

Do we need movies to remind us that the world is indifferent to women's suffering?

Last month, alongside millions of women nationwide, I found myself fighting to prove my own humanity when Georgia and Alabama passed their draconian "heartbeat bills," policies crafted by powerful men to control female bodies. At the same time, I watched innumerable immigrant women have been denied their autonomy, dignity, and lives, even, at the U.S.-Mexico border; I watched in horror as 15 schools were the settings for mass shootings. But it isn't only the news that brings near-constant news of the devastation of women, and the violence that permeates our society—it's also Hollywood.

The movie industry has long overflowed with serial killer stories, whether fictional, like The Silence of the Lambs and Psycho, or based on real events, like Zodiac and Summer of Sam. Netflix also offers series based on murderers, including Mindhunter and You. In May, the streaming platform released the controversial Ted Bundy biopic Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile, which chronicles the escapades of one of history's most violent misogynists: a charming white man who sexually assaulted, mutilated, and murdered up to 100 young women. And, by the way, he's played by Zac Efron, one of the objectively hottest actors in recent memory, because, of course, he is. Karma works in mysterious ways, but this much seems clear: Leave deep bite marks on a woman's body, and you'll get your own glamorous Hollywood twin.

You can blame women for many things, but serial violence is not usually one of them. We don't shoot up abortion clinics. We don't follow strangers home from the bus. We don't generally stalk and kill dozens of youth. Instead, we're near-constantly under siege. In a world that threatens women every day, many of us lock the doors the second we get into our cars at night. We go out for jogs with keys between our fingers. We sit up straight in Lyfts with one hand on the door, prepared, if necessary, to make a run for it.

So naturally, when the trailer for Extremely Wicked was released in January, many women took to the internet, arguing that the film glamorized the very brutality that we face every day. Others rose to its defense, hoping for a multidimensional, nuanced film that did not equate a serial killer with a thirst trap. But that's not what happened. Instead, Extremely Wicked was a one-dimensional, irresponsible film whose self-serving portrayal of Bundy only confirms what women have known all along: Men—particularly white men—will be excused, even celebrated, for violence and misogyny, even as body counts pile up, because it's easier to root for Efron than it is to confront the realities of toxic masculinity in our society.

I'm 18 years old, born decades after the heyday of American serial killers in the 1970s and '80s. Instead, I came of age in the #MeToo era, watching scores of privileged, abusive men taken down by their own victims, publicly smashing the notion that men will take what they want, and women will live with the consequences. So it's always jarring to watch the opposite celebrated on the big screen: to watch men gain popularity, infamy, even lovability for violence against women, while the names of their victims are forgotten, or else relegated to a half-hearted credits roll at the end. The existence of these movies raises disturbing questions about our society's ravenous taste for female oppression at the hands of men.

Recently, I asked female friends what their defense strategies were, in case of a run-in with an errant catcaller or stalker or groper or other male creep. Mine, generally, has been to laugh: to be demure and agreeable in a way that offends my feminist sensibilities, but nonetheless allows me to placate the offender and thus minimize my chances of getting murdered. My friends' strategies ranged from avoiding eye contact to pretending to call their boyfriends, but everyone shared the same, dismal goal: Don't get killed.

So, why do serial killers on film continue to steal hearts and headlines? It's no secret that pop culture often serves as a mirror to our political climate, and there's something natural, even digestible, about seeing white men exact devastating violence against women on TV—because that same story is playing out constantly in our society at large. Men are predators before and behind the camera: In fiction and nonfiction, on and off the screen, the same destructive narrative cycles continue taking their toll on women, seemingly without consequence.

This is not to say that serial killer movies are directly responsible for a culture of violence against women; rather, they reinforce a system in which men are condoned, encouraged, even rewarded for violence and dominance. But, these films do distract and delay from a necessary conversation about the brutality, aggression, and toxicity we have come to expect from white men. More simply: What message are we conveying to white male viewers when their exploits are rendered with cinematic fanfare? What message are we conveying to female victims of violence when their attackers are celebrated on the big screen?

Already, there's the enormous threat of stigma and backlash against women who speak out against men who've hurt them. Whenever I see women testify against their attackers, all I want to do is scream. They have to be calm, credible, controlled as they recount the terrible things that have been done to them. They can't be violent or irrational, not the way men can. And then those same men ask them why they didn't say no, what they were wearing, whether they led anyone on—if you're a woman, you know how this goes. We're told, both by serial killer films and our own justice system, that our stories don't matter. That our suffering is better left anonymous, because, even in death, a woman's trauma is never worth a white man's legacy.

And of course, there is a painful racial element to the serial killer genre that Hollywood often ignores. All of the pretty, haunting, charismatic serial killers from recent films have been white men—Bundy, Charles Manson, Jeffrey Dahmer, and the Zodiac Killer, to name a few. It's part of the shock factor, the plot twist: Presumably, audiences are surprised that these men are capable of such violence, because they look just like the men we're supposed to trust. They are afforded the humanity that our society reserves exclusively for white men: Despite their horrific acts, these serial killers are portrayed with sympathy, love interests, dreams, desires, and soft spots. This is the same humanity that our society has been reluctant to grant to men of color, who historically have been criminalized, villainized, even lynched and beaten and killed for their perceived aggressiveness and danger towards white womanhood. Another interesting paradox: Despite their anonymity, most of the victims of the popular serial killers are white women. Would the same cultural energy be directed towards female victims of color—perhaps the hundreds of missing and murdered indigenous women, or the epidemic of disappeared Black girls from the D.C. metro area, or even the immigrant children at the border?

Serial killer movies, however, are only a reflection of the pervasive societal problems in our society: toxic masculinity, white supremacy, female erasure. They are entertaining, thrilling, perhaps slightly less so if you're a young woman who has to take a good look around at the other patrons of the movie theater before sitting down, just to be safe. They aren't meant to be harmful. They star actors like Efron and Brad Pitt, attracting audiences with their familiar smiles and abs. Despite this, films are powerful, and convey important messages about who gets to live, and who has to die; who gets forgotten, and who gets their story told.