Entertainment

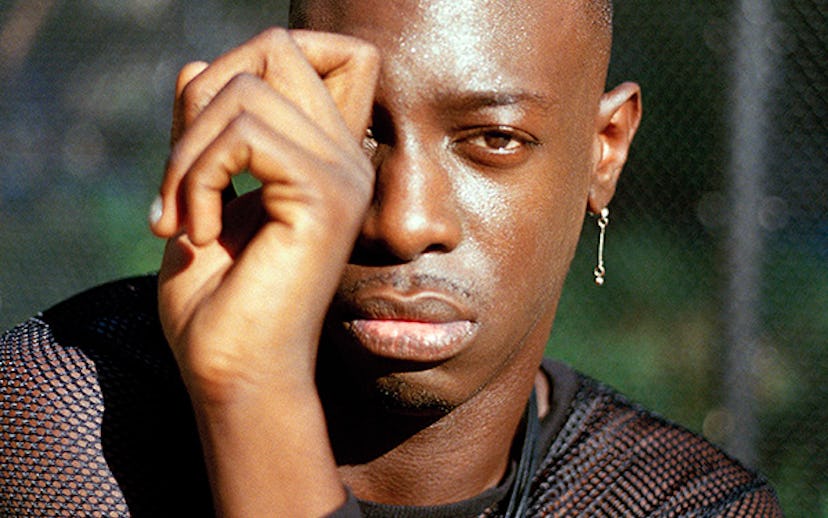

Le1f Takes His Activist Roots To The Club With ‘Riot Boi’

riot on the dance floor

With social justice movements roaring this year, it comes as no surprise that Riot Boi, the debut album from Harlem rapper Le1f, was informed by a “pro-trans, pro-Black Lives Matter, pro-clean water” agenda. What is unexpected is the means by which he delivers this message: On the surface, the 12-track work employs body-moving beats to chronicle a night out that gets ruined by an unwelcome advance. Beyond that, however, the album unpacks the complexities of fetishization, Eurocentric standards of beauty, preconceived notions about black males, and more. Here, we discuss the inspirations behind Riot Boi (out today via XL Recordings) and the 26-year-old musician’s journey thus far.

What's the story that Riot Boi is telling?

From start to finish, it has the concept of feeling cute and going out to the bar and some dude tries to hit on you, but you realize he’s annoying and super-problematic. So, you tell him that he’s a douchebag and leave and go home alone.

Is that based on personal experience?

Yeah, duhhh. [Laughs] Totally. After “Wut,” people would respond to me like, “Oh you don’t hook up with black guys or people of color cause you were sitting on that guy’s lap.” And I was like, but the whole verse is about actually rejecting that guy. So “Koi” [the first single from Riot Boi] was just me being like, “No, this is actually what I said,” for the whole song.

How was the process of creating your album different from making mixtapes?

It was so DIY for so long—this is the first time I’ve had someone else in the room to mix and master it. What really has changed in this process is the clarity of the vocals and the level of production.

What made you choose the social issues that you address throughout the album?

I wanted to be in support of people who have the angst that I’ve had with my identity in the past, and make songs for the club that allow marginalized people, like my peers, to also have fun—to have our voices be a little bit more [present] in the world.

Where did the idea for the track “Grace, Alek, or Naomi” come from?

That was me imagining the super-black, super-futuristic fantasy of the fiercest clique of dark-skinned women. I don’t think people recognize how their beauty is so Afrocentric. There are all these rap songs that are named after girls, like “Girls Love Beyoncé.” I’m like, “Girls love Alek!”

What’s the difference between your reception overseas and how you’re seen in the United States?

I feel like there’s a growing global youth, like a way of seeing the world that felt like the underground before. That doesn’t really exist [in the States] because of our really, really, really fucked-up and young history of maintaining ignorance. Our generation and the one after us are even more liberal and open, especially when it comes to things like sexuality and gender. I think that it will be a cool future at some point. Hopefully.

Between Frank Ocean coming out, Mykki Blanco’s first full-length, and your presence, has the hip-hop landscape become more open to homosexuality?

Not really. I find myself being in this weird space of making records that at the end of the day have—my roommate calls it “tears of a queen.” [Laughs] I’ll be in this moment where I want to make a happy song, and then that will be the single because people want to hear my voice in a campy way.

When you look back at your life as a preteen, how do you feel about how far you’ve come?

When I was in boarding school, I had one gay black friend who was one of the four queer people in the whole school. Even though I did feel like I was in this safe space, it was definitely a white, cis space. I did not know what was going to be my future. I didn’t feel like I was making the connections to have some kind of career. So, it’s kind of amazing to actually be on a label.