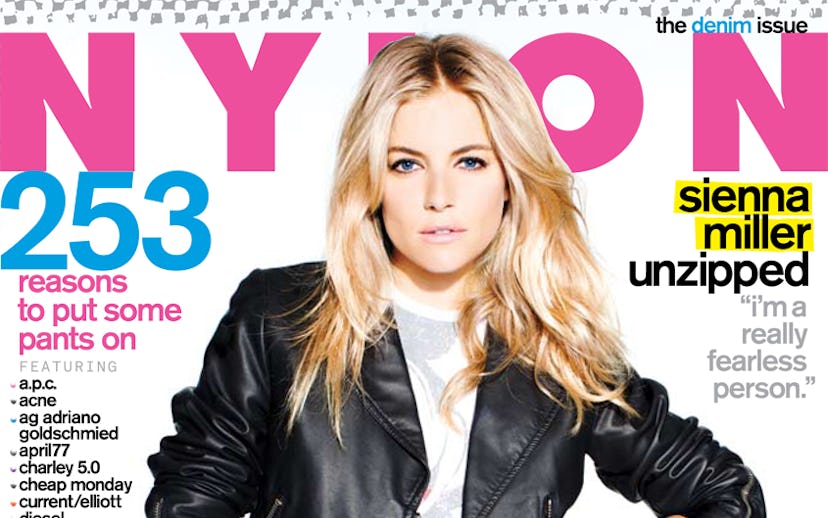

flashback friday: sienna miller

reread our ’09 cover story with the it girl!

It's Flashback Friday time! This week we're time traveling to 2009, where Sienna Miller talked art, fashion, and her new movies with writer Luke Crisell. Read on for more.

Head down, shoulders slumped, hands shoved into the pockets of a blue blazer, toes pointing slightly inward, and heels scuffing the pavement, Sienna Miller is walking down the road like a school girl making her way to the principal's office. When she sees me standing outside the gallery where we were supposed to meet half an hour earlier, she pushes her sunglasses up on her head, smiles a defeated smile, and raises her arms in mock exasperation. "I've been waiting at the wrong gallery!" she says, falling into a hug that would be more appropriate had she just run the London Marathon, not walked a few hundred yards down one of the city's streets. "Total fuck up. Not your fault, of course. You don't hate me, do you?" We are at the brand new Lazarides gallery on Rathbone Place, just off Oxford Street. Steve Lazarides, a champion of subversive art (he exhibits Faile, J.R., Blu, and Polly Morgan, among others), is one of the most forward-thinking art dealers in London, but is perhaps still best known as Banksy's former agent. (He keeps Banksy originals up on the private fourth floor, where the general public can't go.) Immediately inside are two huge paintings by the Berlin-based Australian artistCharlie Isoe, who, for a finishing touch on a picture hanging elsewhere in the gallery, had his girlfriend give him a blow job and spit the semen onto the canvas. "Oh, how fun!" says Miller, laughing upon hearing this. "Is there jizz on these?" As we walk around the space, Miller seems excited by the work on display. Not just pretend-excited because she's with someone who's going to write about how excited she is, but genuinely excited. She owns some art, she says, including two Damien Hirsts, which were gifts from the artist after Miller appeared in a music video he art-directed for the band the Hours in 2008. (She earned them: In the clip, she rubs blood from cow carcasses all over herself and at one point utters the line, "Death feels like the safest place for me right now.") As we go up the stairs, she stops in front of some Banksy pieces. "Oh, I love these," she says. "My ex, Jude [Law], got into him really early." I tell her that the two-foot by two-foot screenprint she's looking at is listed at £200,000. "Jesus, really? You know I couldn't afford most of these pictures," she says. "People think I earn a lot more money for my films than I actually do." Once we arrive at the top floor, which is brilliant in the sunlight streaming through a wide skylight and full of art ("Oh my God, I want to live here!" Miller says, twirling around happily), we sit on a couch directly underneath the Isoe painting with the bodily fluid: a dramatic, nine-foot-high portrait of Marilyn Monroe. Taking off her blazer, Miller scoots in close and tucks her suede boots under her floaty, purple chiffon dress that she's cinched with one of her dad's old belts. She's set up camp well within the parameters of my comfort zone, and her unselfconscious physicality is immediately endearing. To wit, later, when we share a cab across town, and I ask her who makes her dress, she can't remember and insists I look at the label. In order to do that, though, I have to unzip it a little bit. "No problem! Just do it," she says (it turns out to be by Bensoni). When she gets a run in her tights she stands up in the cab to examine it. "Right down the arse!" she exclaims. This engaging familiarity is perhaps even more noticeable than when I interviewed Miller two-and-a-half years ago, but she is no longer the quixotic, even naïve girl she was back then. In the time since, her relationship with the tabloid press reached such an ugly apogee that she fought and won a landmark legal injunction against one of the world's leading paparazzi agencies. She finally made a big-budget film, G.I. Joe: The Rise of the Cobra, that might, at last, make her an actress known for being an actress rather than for whom she's dating, and she has undertaken a life-changing trip to the Democratic Republic of Congo with the International Medical Corps (IMC), from which she's just returned. Now 27, she has become an aunt for the second time—her sister, Savannah, with whom she runs the fashion label Twenty8Twelve, has had another baby, Lyra—and she has bought a cottage in the country ("It's 16th century, and thatched with exposed brick and big open fireplaces! You should come and stay this weekend!"). All in all, she seems, not just happier and calmer, but, well, more grownup. "I do feel that way, actually," she says. "I think a lot of it has to do with fucking up and then growing up because of it." The learning process proved particularly astringent for the actress and was only exacerbated by its scrutiny in the press. "I just started running and not thinking and just living everyday at this crazy pace. Just, 'Fuck everything, just live, just live.' And then I look back at the wake of stuff I've done, and I hadn't really noticed what was going on. And I suddenly had to realize that my life was in a place where I wasn't in control of it." For Miller, who has been a tabloid obsession in the U.K. since she started dating Jude Law in 2004, the decision to take action against an institution so often seen as untouchable (when tabloid papers and magazines and paparazzi agencies get sued, the resulting fines are often a lot less than the profits made from whatever salacious story or photographs they have already printed) was not only an important one for her personally, but could have huge implications for the entire industry. It has opened a door for more and more people in the public eye to not just sue, but using the Human Rights Act, claim protection from the media. Miller has sued numerous newspapers in the U.K. before and won substantial damages, but they always just went after her again. "I was doing a scene for this film, Hippie Hippie Shake [due out later this year], on a private estate where we all had to get naked and swim in this lake because we were hippies and that's what people did," she says. "And a photographer snuck onto the set and hid in a bush all night and got photos of me naked and put it on the cover of the News of the World. Me, full-frontal naked. I don't want to be naked on the cover of a Sunday newspaper! I don't! I don't want people analyzing the shape of my muff!" When Miller was photographed on vacation with Balthazar Getty (who was legally married, but separated) last summer, the attention on her was magnified in both the U.K. and the U.S., where she was involved in carchases with paparazzi so dangerous that she reported them to the police. Her house in Maida Vale, London, was daubed with the word SLUT, huge and in black paint, alongside what looked unnervingly like a satanic symbol, which her mother helped her scrub off ("She was devastated. And she doesn't deserve that," says Sienna). "I got to a point where I was like, 'I will just run away,'" she says. "It was just breaking my spirits, and I had been pretty resilient for a long time. I was not able to leave the house and was living in a state of fear, when I'm a really fearless person." She tugs at a buckle on her boot. "I had a kind of semi-breakdown, if I'm really honest, and everything just became too much. It was cutting me up to the point where I thought it wasn't worth it. I thought, Either I try and take them on, or if I can't, then I don't do this anymore." "I'm stubborn as hell," she continues. "I'd come out of my house in the morning, and [the paparazzi] would be like, 'Who'd you fuck last night?' And I'd be like, 'Fuck you,' right back. I was living life with complete abandon, because everything was always a battle. If anyone puts up boundaries, I tend to knock them down. But things are calmer now. I'm not rebelling against something every day anymore." She leans back and her arm gently touches the painting. "Ew! I just touched the jizz!" Miller's relationship with the press had been fermenting for a while. She was famous before she had appeared in her first movie, Layer Cake, and her star rose considerably faster than she was making the films to justify the ascent. As such, she has never really been taken seriously as an actress, despite being an undeniably talented one. In Factory Girl (2006), she inhabits Edie Sedgwick with tragic compassion; she is electrifying opposite Steve Buscemi as actress Katja Schuurman in Interview (2007); and she is convincing in The Edge of Love (2008) as Dylan Thomas's wife Caitlin MacNamara, opposite her friend Keira Knightley. "I became the target for [paparazzi] attention before I'd had a film come out," she says. "People just want to see you in magazines, they don't want to see you as an actress or a humanitarian or as anything else you claim to be. And then because you're being photographed every day, you become scandalous. Because anyone who's being photographed everyday would look scandalous." Now, Miller wants to remain in the public eye for the right reasons, and what better way to do that than by starring in a summer blockbuster? "It's really exciting to be in a film that people actually want to go and see! I was having to pay people to see my movies!" says Miller, when the subject of the $170million G.I. Joe comes up. Then, more seriously: "There is defi nitely a strategy behind [the decision], yes, because certain really great directors have wanted to do films with me, but unless you've had a film that's opened with a certain amount of money, you're not bankable to studios. That's the way the industry has changed. It wasn't that way for a while, and I was really happy doing independent films, and I think I'm always going to be more comfortable in that art-house environment. But if you want to make amazing, artistic films with the best directors, you've got to have some sort of box-office credibility, which I just don't have."

Miller plays the Baroness in G.I. Joe, for which she wears a black wig, a black leather catsuit, and shoots lots of guns. Swimming in bucolic English lakes naked, this most certainly is not. "I've done a lot of roles where I have emotionally tortured myself, but I wanted to go to work and just have a laugh." So did she have fun making it? "Well, for the fi rst two months I was crying in my trailer going, 'What is this?! What have I done?!'" she says. "Then once I realized what I was in, I was like, 'This is hilarious.'" "It's very much about the result, not about the process, with that kind of film," she says, leaning forward and sketching some stars on my notebook. (Miller has three small stars tattooed on her right shoulder and a dove on her wrist.) "You have to ham it up, and you have to know you're acting for 13-year-old boys. You know you're making something that's pure entertainment, and it's not about your own process or your own anxieties. Like, I'll be in a customs line and the guy will be like [she adopts an American accent], 'Hey, can't wait for G.I. Joe!' I'll be like, 'Woo!' I've never had that with, you know, Factory Girl. Or Interview, which about 12 people have seen." In addition to G.I. Joe, for which Miller signed a three picture deal, the actress has two other movies coming out this year—The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, and Hippie Hippie Shake—and is refreshingly honest about how they fi t into her newly re-evaluated career path. "It's a hard thing, when you do films that don't come out for a while," she says. "Like, I shot The Mysteries of Pittsburgh three years ago, and I can understand why I did it three years ago. But now it's like, 'Please don't come out and ruin all the good stuff I've done since.' It's not the best…." On Hippie Hippie Shake: "I don't think I'd make that film now." Both do seem like remnants from a time in her life when she wasn't being as realistic about what she needs to do to be a successful actress (she describes the films as having "crept up on her from the past", and are incongruous with the Miller of now, who is focused, determined, and practical. Where she used to hop from low-budget film set to low-budget film set, for example, she hasn't made a film since G.I. Joe. This August, she will move to New York City (where she was born and lived until she was two) to star in the title role of the Broadway production of After Miss Julie, co-starring Johnny Lee Miller. "I'm so excited! Will you be my friend?" she says, of moving to New York. Miller lived in the city when she was 18, attending the Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute ("Where Marilyn Monroe and James Dean and Marlon Brando went, so you get all these characters who come there wanting to be them"), living for a while with her father, an investment banker from Pennsylvania, who now lives in the U.S. Virgin Islands. "I got kicked out of his fl at for smoking pot," she says with a grin. (A few days earlier, her father surprised her at the photo shoot for this story, where her mother, Josephine, a former model who was born in South Africa and once served as a P.A. to David Bowie, already was—they divorced when Sienna was six. "Daddy!" she screamed, running across the room and practically jumping into his arms. Her dog, Porgy, looked on delightedly.) Miller continued to drift around New York City "like a gypsy" and ended up in a model apartment on Maiden Lane, in the Financial District, with some friends. "They were all male models, and I was like the mum," she recollects with a smile. "I was the Maiden of Maiden Lane!" Recently, she wrote a short film about the experience. "Oh my God!" she yelps when I bring it up. "How on Earth do you know about that?! I don't think I've ever told anyone about it. But yes, it's true. I like to write when I've had a few glasses of wine, then you can't prise the pen away. I suddenly realized when I was in the Democratic Republic of Congo and writing that blog that I love doing that—as opposed to pissed poems that you fi nd in the morning, and you're like, 'Oh God, why did I write that?' I can be quite pretentious in my writing." Such self-deprecation is typical of Miller, who describes herself as "pretentious" nine times during our conversation (and "cliché" fi ve more), but her blog from the DRC was both eloquent and moving. (The Huffington Post put up each of her reports, to an overwhelmingly positive reaction, and when I tell her that the comments were not only encouraging but furthered her cause—one, for example, directs readers to a Washington Post article about the treatment of women in the DRC—Miller, who has deliberately avoided reading them, is elated: "Oh, my God, that's so fantastic. Go, Huffington Post!") She was asked to visit the country by the IMC and was immediately won over by their cause. "Among the many facts they told me is that a woman is raped there every eight minutes," she says. "I wanted to go there and see where the money was going. I get asked to do a lot of stuff for charity, and I always donate something signed if there's an auction, which just feels crap. And actually, why would anyone want to buy it?" When she talks about her experience in the Congo, Miller is both passionate and hesitant. As much as she believes in the efforts of the IMC to raise awareness of the effects the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo is having on the women and children in the country, and as much as she wants to talk about it, she is very conscious of the criticisms leveled at celebrities who undertake charity work. "If I'd done it for publicity, I would have taken a photographer," she says flatly. "I know that I have integrity, and I know that my reasons are pure in doing it. But it's the celebrity condition: People will always fi nd the negative in everything you do. But at the same time, I'm not just lending my name to it. We went to a war zone; we lived in camps. I would like to see those [detractors] in the Congo, doing the journey we did." One particularly powerful encounter Miller described in a blog post was with a young woman who had been raped so brutally that she will have to use a colostomy bag for the rest of her life. She speaks about it quietly now. "I was just looking into her eyes, and she was utterly broken. How can you have hope? She had been raped by men with the butt of a rifle. Her whole stomach had been split open, and I saw it: She was scarred all the way down." Miller is clearly still traumatized by the experience. She looks across the room, out of the window. "We're so fucking lucky." The whisper is barely audible. She puts her head in her hands. Miller is well aware that she's able to share these stories because of her fame. "I basically realized that I was so resentful for so long about the state of my celebrity, but I wanted to turn it around and do something good." She pauses and sighs. "But then, the kind of newspapers that write trash about me don't want to print that I'm actually doing something good in the Congo. The Internet has been really good in that sense, because the magazines that have made money off me being a certain way will not condone me being philanthropic." I ask her whether, given the opportunities her fame provides her with, she would push a button and become anonymous. "I already pressed it when I sued," she answers. "And I have a life again." I ask her if she had any reservations about doing that. "I think it depends on what kind of actor you want to be," she says. "I don't want to be a movie star. I want to be an actor. I don't mind if I do plays. I don't mind if I do independent films. It's not about being the best and the most successful. The people whom I tend to love and respond to most when I'm watching films are the people who I don't really know anything about. That's the kind of actor I want to be. And to have that mystery completely invaded, and your own personal sense of mystery exploited everyday and lied about and hyperbolized makes my job really difficult. How am I going to convince anyone? How are you supposed to convince anyone of the character you're playing if people go, 'Oh, she's the girl that, dot dot dot.'" She pauses and readjusts herself on the couch so that she's facing me again. "I've always been pathologically optimistic. My way of dealing with fame and celebrity was to pretend like it didn't exist and carry on living exactly as I would have done if I wasn't famous. But you can't pretend it's not there and just be like, 'Fuck them, I wanna go out and get pissed with my friends.' You have to take into account that people are watching every step you take and every stumble out of pubs. Now, I'm more grown up. I can do whatever I want. I just have to protect myself a bit more. I can't keep pretending this doesn't exist, because it does." As we're leaving the gallery, Miller notices another Banksy on the wall, bearing the words I FOUGHT THE WAR AND I WON in large, red letters and reads the phrase aloud. "How appropriate!" she says, happily. "I should own that." -- LIKE CRISELL