Entertainment

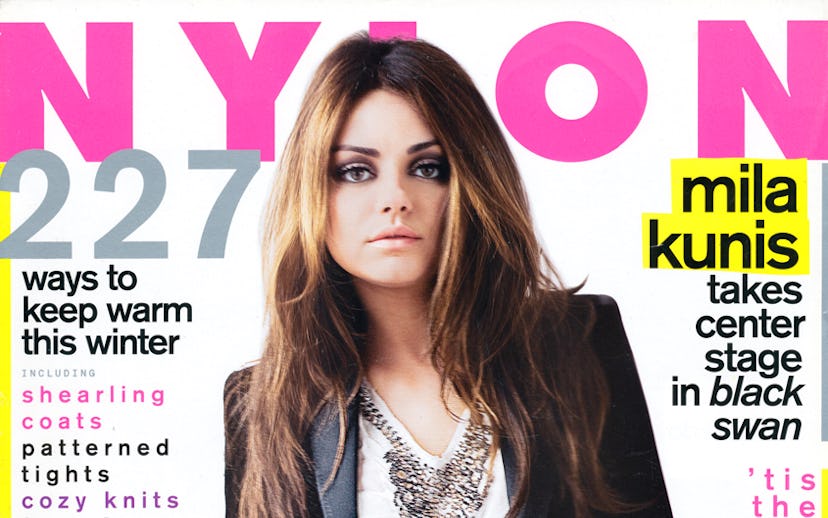

throwback thursday: mila kunis as our sultry cover star

from jackie to ‘jupiter ascending.’

With her new film Jupiter Ascending hitting theaters this weekend and the recent birth of her daughter Wyatt with beau Ashton Kutcher, Mila Kunis is doing better than ever. From That 70's Show to Black Swan, the hilarious actress has long been one of our on-screen idols, and we can't wait to see what she has in store for the rest of 2015. Until then, we're throwing it back with our December 2011 interview with the siren and reflecting on some of our favorite Mila moments ever. Read below to hear where the new mom was when we talked to her just four years ago.

She had been working as a model and actress for 11 years, had starred in a number of forgettable movies, and was six years into an eight-year contract with That ’70s Show. “And I was like, ‘All right, this has been a good run, but I’m done,’” she says. “I wanted to rethink my life for a minute, because I didn’t think acting could be a career. This is the worst industry you can put yourself in because there’s no security whatsoever. I mean, none. The whole thing is based so much on opinion and nobody is wrong. That person can think I’m great, that person can think I suck, and they’re both right. I was just like, ‘Can I really do this for the rest of my life?’”

But while Kunis might have had her fair share of bad reviews and disappointments, she was at least financially secure. “What a lot of people don’t realize is that you make more money in TV than you will in film; it’s a very steady salary,” she says. “An obscene amount of money gets given to you for, like...what? So I was 20, and I looked at my bank account and realized that I was secure for the rest of my life. I was like, ‘I’m OK. I can go do other things now.’ I had been happy being poor, so having money made no difference to me. I know people with money say that, but it’s the truth. Of course, it’s a blessing to feel like you have a roof over your head and not having to worry about where your next meal is coming from. But that blessing, I realized, comes at a price.”

Kunis’s existential crisis was welcomed by her parents—“They were like, ‘Great! Now go to college’”—but not so much by her manager, who had signed Kunis when she was nine years old: “She was like, ‘You’re crazy.’” Nevertheless, Kunis took some time

to soul search. “I was contemplating whether I wanted to keep doing this or if I wanted to go and explore life. And I realized that acting is the one thing I love to do. I asked myself, ‘What else could I do that would make me happy? What else could I do where I wake up in the morning and think, I get to go to work and do something great and have fun? I couldn’t think of anything else. So I was like, ‘I’m stuck doing this because I actually, truly, love it.’” And so, three weeks after she first considered quitting acting for good, she was back in the saddle.

It’s early one Friday afternoon in October and Kunis and I are sitting in a cabana beside a hotel pool in Santa Monica, California. In contrast to most of the hotel pools in Hollywood, this is not the kind of place where people come to see, or to be seen. It’s surrounded by tall boxwood hedges and is particularly, unusually peaceful; apart from the nondescript house music playing quietly from unseen speakers, the only other noise is the hushed conversations of a few business lunches which have gone on longer than they should have. In a corner, a man in his forties is perched on the edge of a sun lounger playing an electric guitar with headphones on and eyes closed, a contented smile on his white-whiskered face. A few women are sunbathing, iPods in, brightly colored cocktails on glass tables next

to them. The sun is sparkling on the water. Kunis is wearing a gray blazer with the sleeves rolled up over a loose, white tank top, the neckline of which is low enough that her beige bra is clearly visible. Her black jeans are ripped all over and her black, buckled, calf-high leather boots look expensive but, apparently, aren’t at all. “I bought them four years ago at some store on Melrose for like, $20!” she says. “Aren’t they great?!” She takes a sip from her huge Dunkin’ Donuts iced coffee, her hand—freshly manicured nails a shade of stormy blue—barely fitting around the cup. “Well,” she says, a slightly mischievous grin spreading across her face, “what shall we talk about?”

Now 27, Kunis’s career has never looked brighter. This December she can be seen in Black Swan, a dark thriller directed by Darren Aronofsky, the visionary behind Requiem for a Dream, Pi, and The Wrestler. It is by far the best film Kunis has ever starred in, and she delivers a career-defining performance; she picked up the Marcello Mastroianni Award for Best Young/Emerging Actor at the Venice Film Festival, where Black Swan premiered earlier this year. Finally, it seems the actress is proving what she’s known all along: that she’s much, much more than just a pretty face.

But, to be fair, hers is an exceptionally, distractingly beautiful face. You notice the eyes first: They’re huge, almost caricature-like, and ever-so-slightly different colors. When she was younger, the difference was more obvious, and, although it’s subtler now, it’s still there, if you look closely enough. The left one is a little greener than the right, which is more of a hazel. “As I’ve gotten older, I’ve kind of grown into them,” she says, smiling. “You should have seen me when I was a kid with this tiny face and these huge bug eyes! I looked ridiculous!” Kunis’s eyes lend her face an exoticism that’s set off by long, dark hair which today hangs artfully dishevelled around her shoulders. Although one of her first-ever jobs was a Payless shoes commercial for the Spanish network Telemundo because, she says, “I looked Hispanic when I was little,” as an adult her Eastern European heritage is far more obvious, even with her glowing tan.

Kunis was born Milena Markovna Kunis in Kiev, Ukraine, in 1983, and when her parents brought her and her older brother Michael to America in 1991, she couldn’t speak a word of English. “It was Communist Russia,” she says, “and I think my parents just wanted my brother and me to have a better life—well, to have a future. The move wasn’t for them. When you leave, you leave everything behind—your finances, your diplomas, everything; nothing is transferable. You come with nothing, and you’re piss-poor.” She remembers Ukraine fondly. “I had a great childhood there,” she says. “A fantastic one. It was incredibly safe. We only had two channels on television so kids didn’t stay home and watch TV, and we ran around the neighborhood, climbed trees, played cops and robbers. It was really amazing.” Upon arriving in the U.S., Kunis’s parents settled in Southern California and enrolled their daughter in a weekly acting class with the intention that she could learn English and mix with American kids. Kunis describes it as “basically having a babysitter for six hours.” But, this being Los Angeles, one day a Hollywood manager drove past, saw a bunch of cute kids, and decided to investigate further. “It’s such a bizarre thing to try and explain,” Kunis says. “It’s not like any little kids can or cannot act. It’s a matter of if you’re cute or if you’re not cute. That’s all it comes down to.” Kunis was cute, and after a class showcase, her parents found themselves fielding calls from agencies wanting to represent her. “The whole thing is absurd, very fake,” she says. “My parents were like, ‘We work full time. We don’t have the time

or money to do this. Our kid needs to go to school.’ So they told me to make the decision and I ended up picking my manager, Susan, who had stopped by that day. When they asked me why, I had no idea. I just had a good vibe about her.” Shortly afterward, Kunis was cast in a spec commercial for a camping Barbie that was never produced (“I hated Barbies! I’d rather run around with my brother and his friends climbing trees and banging my knees—I wore a skirt or a dress while doing it, but still”), and, just like that, at nine years old, she was a working actress.

“My parents were so completely against me doing it,” she says. They were the opposite of what all the parents are in this industry. They never went to set, ever. They would be like, ‘Please be a kid, go to college.’” Kunis saw acting as just an after-school activity, not the beginning of a career. “It was just play-pretend,” she says, tucking her legs up onto the bench. “Trust me, I did not have a clue what I was doing. It wasn’t a job for me, I didn’t think anything other than a teacher, a doctor, a lawyer, a fireman, or a policeman was a legitimate job because when you’re little those are the things you see. It wasn’t until I was 20 that I thought I could actually make it a career.” Her manager, Susan Curtis, is still her manager now and Kunis speaks to her multiple times a day. “Her family and my family are entwined at this point,” she says. “They travel together, they’re best friends. She is my family.”

When she was 14, Kunis auditioned for a new sitcom on FOX called That ’70s Show about a group of teenagers living in the fictional suburban town of Point Place, Wisconsin, in the late ’70s. In order to audition, actors had to be 18 years old or legally emancipated, and it’s an oft-repeated rumor that Kunis, who was neither, staged some kind of elaborate deception to get the part. “It’s exaggerated,” Kunis says. “Here’s the truth: I was 14 when I auditioned and, yes, you had to be 18 or legally emancipated and when they asked if I was legally emancipated I was like, ‘Sure, sure.’ I just played along with it. But by the third audition, they knew. Because I had to sign the contract and I specified that I needed a studio teacher and they were like, ‘Why?’ and I was like, ‘By the way, I’m still 14; I’m still in high school.’” The show, which was on air for eight seasons, was a slow-burning hit, with each of the other five “teenage” leads—Ashton Kutcher, Laura Prepon, Wilmer Valderrama, Topher Grace, and Danny Masterson going on to achieve further success when it eventually ended. Kunis was perfectly cast as the pretty, spoiled Jackie Burkhart, who starts off the first season as immature and obnoxious but gradually becomes more thoughtful, dating all the boys apart from Eric (Grace) in the process. “I went through everything on that show,” Kunis says. “I went through puberty. I celebrated my 16th birthday and my 21st birthday on it. My entire life was on that show. But the beauty of it was that after work I would go home and have a normal life. My life was never around the industry. I could hang out with my best friends—who are now a teacher and a dentist—I went to school, I went to work, and we finished at the same time so we could hang out afterwards.” In her breaks (the show shot on a schedule of three weeks on, one week off, then two weeks on, one week off) Kunis attended school at Fairfax High in L.A. Considering her peers were the show’s target audience, things were a little strange in the classroom. “It was weird, yes,” she says. “But I promised my parents I would go to school, so I did.”

During hiatuses, Kunis took parts in a handful of films, including American Psycho II (which went straight to video), Tony N’ Tina’s Wedding, and Krippendorf’s Tribe, in which an anthropologist has his family pretend they’re a lost tribe from New Guinea in order to cover up the fact he’s spent all of his grant money. Slightly better was After Sex, Eric Amadio’s 2007 indie comedy which examines modern day relationships and intimacy through the stories of nine couples talking immediately after intercourse (Kunis’s partner is Zoë Saldana, her roommate). The movies were commercial and critical failures, and, understandably, Kunis doesn’t really want to dwell on them now. “We don’t need to discuss those!” she says, laughing. “I just did films because they were going to be fun! I never thought about it for a long career. At the age of 16, I was just like, ‘I wanna go to college and do something else.’ I don’t regret them, because I wouldn’t be where I am without doing those. I don’t regret anything I’ve ever done. Even the dumbest shit I’ve done in my life—and believe you me, I’ve done some really dumb shit—I don’t regret doing it. I’m not talking about projects, but just the stupid things that a kid does, that a teenager does, that a person in their twenties does. I did everything. I was never a bad kid, but I did things that weren’t necessarily good, or smart decisions. But I did learn from them. My parents always said to learn from other people’s mistakes, but I always seem to have only learned from my own.”

In 2000, she landed a role she still has today, when she took over from Lacey Chabert as the voice of Meg Griffin, the daughter of the dysfunctional Peter and Lois Griffin, on Seth MacFarlane’s wildly popular animated FOX show Family Guy. “It’s the greatest gig ever,” Kunis says of the part. “I go in once a month, and I record for about two hours. I’m so proud of it; I got so lucky doing that show. Unbeknownst to me when I started doing it, it is actually brilliant. I’d never heard of it, so I had no idea. Then I saw it and was like, ‘Oh my God, this show’s so scandalous!’” And as if That ’70s Show hadn’t garnered Kunis enough pothead fans, Family Guy has ensured her legions more. “It’s the greatest fanbase ever, but weird,” Kunis says. “They’re all fucking stoners! It’s the largest fanbase of anything I’ve done, I hope it never goes off the air.” She pauses to sip the last of the iced coffee from her cup. “It’s such a fun job! Everybody knows that. Every actor wants an animated job.”

The check paid, we head back out onto the sidewalk into the late-afternoon sun. Kunis is staring intently at a seemingly innocuous man on the opposite side of the street who is wearing a blue shirt, shorts, and carrying a black bag. “You see that guy?” she says, gesturing at him. “Watch him. He’s going to walk behind that bus and come out of the other side with a camera and take our picture.” Sure enough, as we pass the bus, the guy pops out and takes our picture (they’re online a few hours later). “It’s anybody now,” she says, walking more briskly back to the hotel as the guy tracks us on the other side of the street, still trying to be covert. “And anybody can tip them off. I don’t want to be the actress who complains about it, but yeah, it’s annoying. I don’t like it and I don’t feel like I ask for it either, so I don’t think it’s fair.” Kunis says she was shocked by the aggression of the paparazzi in New York, where she was recently filming Friends with Benefits, opposite Justin Timberlake. The film, directed by Will Gluck (Easy A), opens next summer and tells the story of two best friends who decide to start sleeping together, no strings attached. “I’ve never seen people in my life with so little respect,” she says. “I’m not saying paparazzi in L.A. have any respect, but at least there’s a distance being kept”—she nods her head at our new friend, who is currently pretending to examine something in a shop window on the other side of the street. “When we were filming on the street in New York it was pure and utter insanity.”

We arrive back at the hotel and head over to the valet—Kunis is going home now, to get her costume ready for a Halloween party the following evening. “My happiness has never depended upon this industry or this career,” she says, pushing some hair behind her ear. “It never has, and it never will. This industry just blows in general; it’s a rough thing to get into, let alone sustain. Who you are should never be dependent on what you do, because then your happiness is dependent upon something that’s very unpredictable—intangible, almost.” She gives me a hug, and tries to pay the valet, who waives the charge. She thanks him, shoots me a quick smile, then puts her head down and walks briskly to her large, black car. Popping out from behind a bush, the guy with the camera takes a few final shots.