Beauty

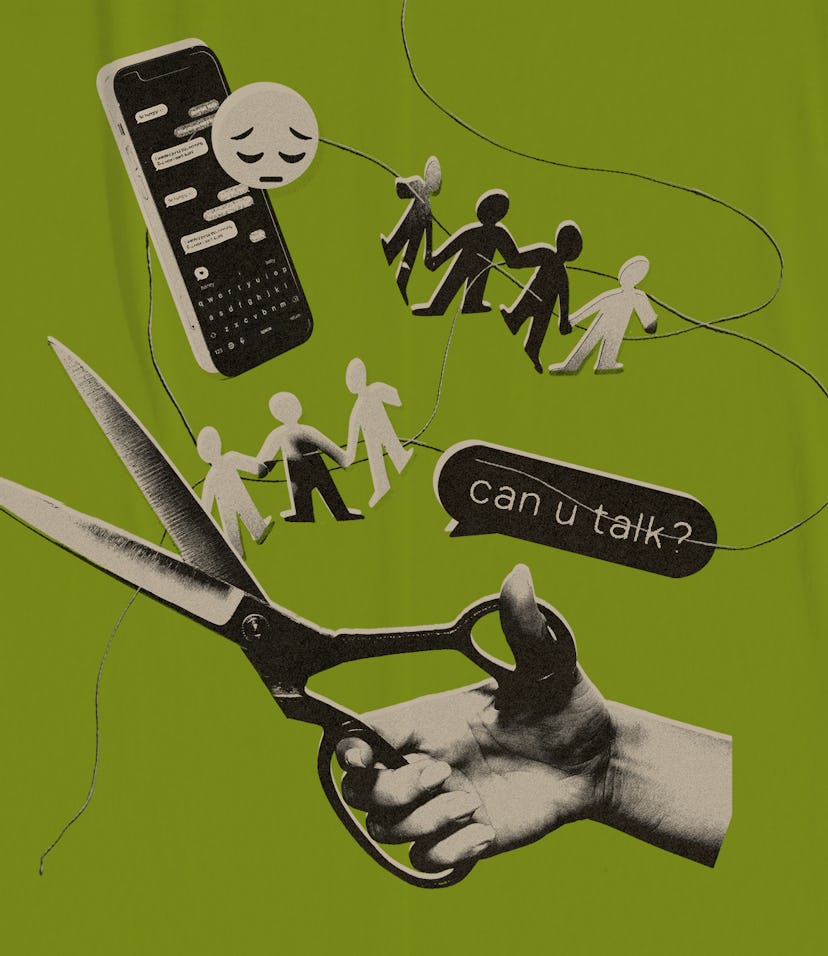

Is Wellness Culture Making Us Worse Friends?

The individual focus of wellness might be harming us in unexpected ways.

It was only a few months after my father passed in 2020 that a close friend of mine initiated our friendship breakup via text. “I’m trying to align myself with people who share my beliefs about wellness and positivity,” she wrote me after canceling plans. A few weeks before, she’d informed me that she stopped listening to anything but upbeat music, referenced a couple of QAnon Instagram accounts (the wellness world has a conspiracy problem), and refused to discuss current events of the world, despite the ongoing pandemic.

While drastic, my friend was not alone in her actions. “Self-love” culture and recently wellness trends (for example the “that girl” trend on TikTok glorifying socializing less and exercising more) are increasingly playing into our rampant individualism. As a mainstream dedication to wellness becomes more of an ideology than just a hobby, disputes are bound to arise. Wellness accounts across the internet are encouraging people to cut ties with friends that don’t give off “good vibes only.” “Alpha females don’t run in packs. She’s often alone, keeps her circle small, knows her power, and works in silence,” says one viral TikTok, suggesting women have few friends for the sake of productivity.

Before that, the “I'm actually at my emotional capacity” text template, which circulated after being posted by activist and writer Melissa Fabello in 2019 (and then swiftly became meme-ified), was the prime example of how to deprioritize your relationships for the sake of self-care. This glossed (or Goop-ed) over the fact that the self-care movement was started as a radical movement for Black women by Audre Lorde, who first wrote about self-care in her 1988 essay collection A Burst of Light. The idea of taking time for yourself in order to better take on systemic inequalities soon become co-opted by white people as permission to opt out of anything difficult, including relationships. This also ties into the wellness industry at large, which perpetuates the idea that being “healthy” means being thin, white, and able-bodied.

Then there’s the controversial New York Times article “How to Rearrange Your Post-Pandemic ‘Friendscape,’” published last summer, which initially encouraged people to cut ties with depressed or fat friends in fear of also becoming depressed or fat. After Twitter backlash, the article has now been updated, but it initially reflected harmful fatphobic thinking. As if cutting off your fat friends for their weight wasn’t brutal enough, this ideology also has harmful real-world implications for those not surviving the friendship audit. According to a 2015 study, fat people who feel discriminated against have shorter life expectancies than fat people who don't.

Bobo Matjila, online philosopher and co-host of the Bobo and Flex podcast, says she has lost “almost all” of her friends because she has chronic depression. But she doesn’t believe this needs to be the case. “It's very possible to support someone who is mentally unwell while taking care of your own mental health if you set boundaries and communicate your limits,” she told NYLON. This looks different for everyone but could be as simple as coming up with a way your friend can let you know they’re OK when they’re not in the mood to talk. Matjila says cutting off a friend in need not only indicates a transactional view of relationships but is also elitist “in a world where mental health resources are only reserved for those who can afford them.” Who are those without resources supposed to rely on?

Research shows that striving for connection and community instead is actually far more beneficial for collective mental health.

Matjila views the problematic wellness culture as a derivative of the cult of individualism. “It prioritizes individual wellness over communal wellness, which is a paradox because there is no individual wellness without community,” she asserts. “One of the consequences of wellness culture is the false notion that relationships should be a constant stream of 'good feelings.' So as soon as a relationship gets even remotely uncomfortable, people run.”

Carl Cederström, associate professor at Stockholm University and co-author of The Wellness Syndrome, says that in an era where we’ve never been more obsessed with optimizing our lives for productivity, wellness has become a stand-in for morality. “Today, in order to be worthy of being seen and treated morally well, you need to demonstrate that you’re healthy,” he told NYLON. “In other words, you must go to the gym and show that you think positively.”

While distancing yourself from friends or family that are causing you mental harm is one thing, Cederström believes the current approach to friendships, through the lens of toxic wellness ideology, creates a lack of empathy for those around us. “There’s a lack of empathy when someone with a desirable body type views someone with an undesirable body in a punishing society as a threat to their personal progress,” he says. In other words, aligning yourself with only other privileged people is a surefire way to remain sheltered and feed your vanity. “It’s individualistic but also driven by competition.”

It would be impossible not to mention the role that capitalist society plays in the demise of modern friendships. Aside from encouraging individualism and leaving us all with very little time outside of work, the capitalist mentality encourages us to view relationships as an exchange of goods. In his book Friendship: Development, Ecology, and Evolution of a Relationship, anthropologist Dan Hruschka argues that human friendship can’t be based on reciprocity, but needs to be based on individual needs (which are relative to circumstance). This includes giving to people you love without the expectation of repayment.

Research shows that striving for connection and community instead is actually far more beneficial for collective mental health. In fact, a 2017 study showed that rising individualism within society is having negative mental health consequences. In spite of this, the wellness industry continues to convince us that we don’t need each other, as long we have our green juices and weights. The global wellness market was estimated to be worth $4.5 trillion in 2018, making it more than half as large as the total global health economy.

Cederström calls this issue “wellness syndrome.” He believes that our focus on self-care has begun to work against us, which makes us feel worse and, ultimately, withdrawn. To test out the true impact, he and co-author André Spicer spent one year inside the optimization movement for their book Desperately Seeking Self-Improvement.

From taking performance-enhancing drugs and trying different work methods to entering a weight-lifting competition, Cederström says his own relationship went sour with Spicer during the year focused on mainstream wellness methods. “More than anything, the relationship that you develop to yourself through these methods becomes a very sort of narcissistic and egotistical pursuit of betterment,” he says. “And through that very masochistic way of treating and relating to yourself, that obsession disconnects you from others. You’re building a ‘perfect’ version of you but it’s one that’s not great at relationships.”

As we’re continually encouraged to view ourselves as never-ending self-improvement projects and discard anyone that can’t “get on our level,” we have to ask ourselves: at what cost? The pandemic may have disconnected us physically from our communities like never before, but it also taught us that true health and wellness cannot be achieved alone.

Perpetuating harmful wellness ideology excludes and demonizes people in larger bodies, disabled bodies, or those experiencing mental health issues. It ensures that wellness is only accessible to the elite few that have access to the latest treatments, therapy, healthy food, gyms, and enough time to bother with it at all. In contrast, a community-focused approach to wellness recognizes that true health is collective. “Self-love can only come from healthy companionship and community,” says Matjila. “If we all understood that we can only be well if we take care of each other, we would be much better friends to each other.”

This article was originally published on