beauty

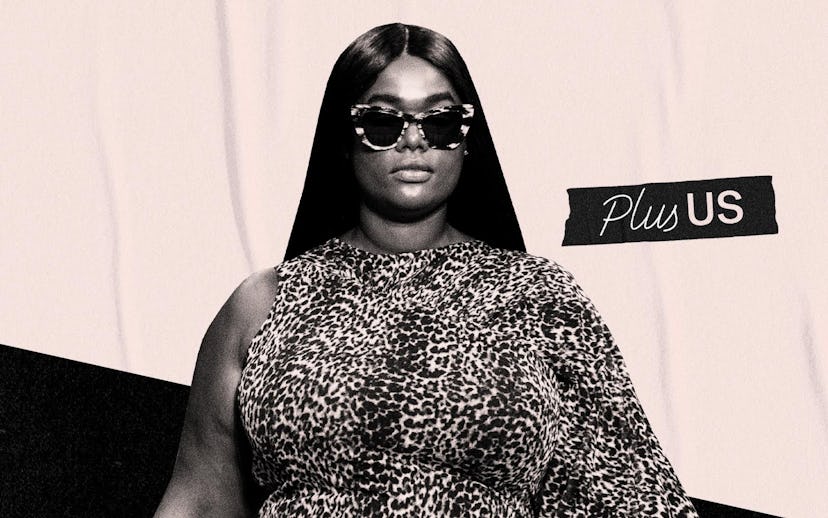

Will Plus-Size Fashion Ever Pay Black Women Their Dues?

One fact remains indisputable in the plus fashion industry: Black women paved the way.

The genesis of plus-size fashion as we know it remains highly debated. Some credit it to the launch of Lane Bryant in 1904, while others point to the rise of the first curvy supermodels in the 1990s, like Emme and Angellika Morton. Regardless of the start date, one fact remains indisputable: Black women paved the way.

Black women lay at the core of the industry: setting trends, making noise, and demanding change in profound ways. Yet consistently, their work is largely ignored and erased from the narrative. When will designers, brands, and the media start paying them their dues, both figuratively and literally?

“Why aren’t Black women profiting from the movement they started?” says writer Jess Sims, pointing to those who started the fat liberation movement in the 1960s and 70s. “So often, not only does the industry not include very many Black women, but they don't include dark-skinned Black women, or they don't include any fat women who are not an hourglass shape. It's a very straight-size view of body positivity.”

The commercialization of body positivity has shifted its view from a lens of liberation to a marketing tactic, propelling white voices to the forefront time and time again. Black models remain tokenized; Black influencers are given less opportunities; and fat Black women, as a whole, stay less respected, Sims explains.

This erasure does more than simply exclude Black women from the conversation, however. It goes as far as to say that they are unwelcome — especially if they fall under the additional intersectionalities of being queer, higher on the size spectrum, disabled, dark-skinned, etc. “It pushes people to believe, ‘Well I'm not white-adjacent, so this movement must not be for me,’ and that’s the real erasure,” Sims explains.

For Gess Pugh, a New York City-based model, honoring those who paved the way for her is central to her mission as a future changemaker. She attributes the start of her style journey to Gabi Gregg, a plus-size fashion pioneer who has led the industry to new bounds. Also a major inspiration: Toccara Jones, the first Black, curvy woman to compete on "America’s Next Top Model" back in 2004.

“Seeing someone that was dark skinned like me, who was a little bit fuller, and who went on to do Vogue Italia was just so powerful,” Pugh recalls. “She just owned who she was, and she owned her femininity, and she owned her body, which was so rare.”

For many, Pugh included, Toccara serves as a prime example of how Black women can be easily erased from the industry. Despite international appeal and acclaim, her star quickly seemed to fade as Ashley Graham and a new generation of (mostly white, mostly mid-size) models took the reins.

However, change seems imminent, with models like Paloma Elsesser and Precious Lee making historic moves in the industry. But Sims is still hesitant to jump on the bandwagon. She notes that, while both women have had incredible careers, their success toils the line of tokenization, and plays into a harmful narrative within the plus community that only allows one voice to be centered at a time. Now that Graham has reached mainstream celebrity status, Elsesser seems to be taking her place in the eyes of designers, editors, and the CFDA. And once her star rises to new heights, Sims believes Lee will be next. She notes that both women are on the smaller side of the size spectrum, with Elsesser also being of a lighter skin tone. “And I think Precious has certain features that white people will find exotic or be attracted to,” she explains.

The erasure of Black women in plus-size fashion is a systemic issue, meaning that change will not come as easily as casting a token woman of color on the Versace runway. Acknowledging those who led the way is only the first step; from there, designers and brands must incorporate Black voices into their DNA, adequately compensating them and elevating their voices.

“White people — plus or not — need to understand that Black women were the first ones to speak out against this in direct opposition to racism, fighting against these harmful stereotypes that they are sloppy or lazy or have no self control,” Pugh says.

Following the murder of George Floyd last June — and the subsequent protests in support of Black Lives Matter — many fashion brands came forward with new diversity initiatives, opening their eyes to the free advice Black activists had been recommending for years. Now, nine months later, many have fallen flat, especially within the size-inclusive fashion space. Few seem to understand the difference between equality and equity, and the ways change must be implemented internally.

Sims shoutouts 11 Honore and Ashley Stewart for their efforts, as well as Eloquii, which recently launched a handful of initiatives in order to spotlight Black women in the industry. The brand partnered with Marie Denee of The Curvy Fashionista on The Cultivate Award, a new initiative aimed to support BIPOC designers financially and through mentorship. Eloquii also launched The Black Creatives Project, which ensures that “a minimum of 50 percent of total paid influencer partnerships go to Black creators, with a minimum of 25 percent going to micro influencers.”

Fashion to Figure has made steps, too, centering Black models in their campaign imagery while partnering with pioneers like Chastity Garner Valentine — as well as others to come later this year — on capsule collections. Kellie Brown of And I Get Dressed has also announced a collection coming with Amazon’s The Drop.

But much is left to be seen. Dark-skinned, fatter women like Saucyé West are waiting to for their time to come, among others. Change is impossible, however, without a joint community effort to progress forward. “It’s more than just saying you’ll be there to support us,” Sims says. “It’s about showing up with your wallets open.”

Pugh adds, “More fashion brands and the industry as a whole need to accept the fullness of Blackness and not just women who are closer to white passing or ‘palatable.’ We need to really embrace the diversity of what it means to be Black.”

This article was originally published on