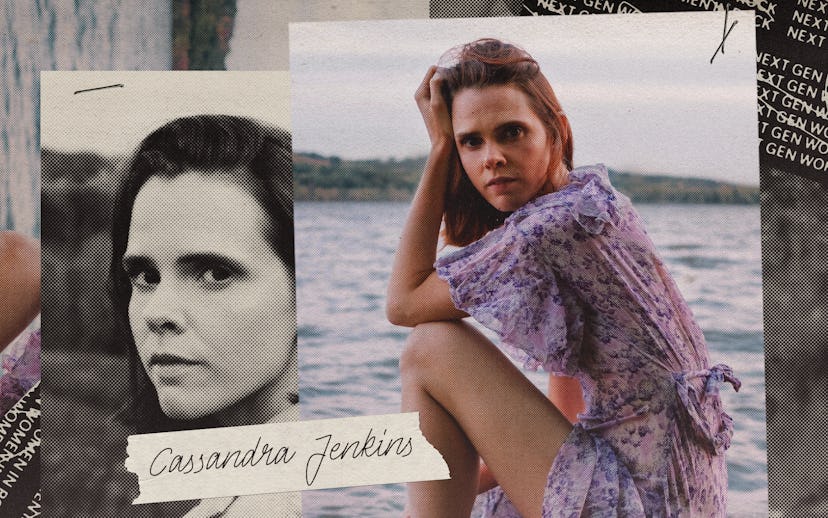

Next Gen: Women In Rock

Cassandra Jenkins Is A Folk Musician With A Birdwatcher’s Soul

She had one of this year’s best reviewed albums. Here’s what comes next.

If you want to feel the warmth of pre-pandemic life, listen to Cassandra Jenkins’ An Overview on Phenomenal Nature. The veteran artist’s heartfelt second studio album, released earlier this year, is animated by both intimate moments with loved ones and encounters with memorable strangers. Its seven stunning songs span a trip to The Met, a plunge in the Norwegian Sea, and a joyful day bird watching in Central Park.

A career musician who has played with Craig Finn, Eleanor Friedberger, and Lola Kirke, there’s an opus-like quality to Phenomenal Nature in its singular confluence of joys, traumas, and lessons, something Jenkins says she’s learned to channel more and more directly into her work.

“A lot of stuff has happened to me over the past few years that really pushed me to be thankful for my experiences and realize that those are my experiences alone,” Jenkins says. “Really settling into this idea that everyone is an expert at something, and it’s their own life.”

From the album’s first line (“I’m a three-legged dog, working with what I got”), it’s clear that Jenkins has made a record that will resonate deeply with anyone who is soldiering on, looking for the beauty in human connection that can help us propel through tragedy, something many of us won’t be taking for granted anytime soon.

Here, Jenkins contemplates translating this new record to the live space, the resilience of New York life, and music as a tool for nurturing goodness in others.

You’ve been making music for a long time; does Phenomenal Nature feel to you like a new phase of your career?

I definitely have a new audience and a new way of interacting with the world. To me, it feels like I have a different job now, but I’m still gonna keep on playing music the way I always have. I’m currently spending a lot more time talking about music than I am playing it, for sure. These things, they come and go as seasons. I think I’ll have another season where I’m not talking to a soul and I’m just writing. But right now, it’s exciting to be heard by an audience that seems to really understand some of the things that I’m talking about. And that is tremendously healing.

I’m doing all of this while I’ve spent the majority of my time completely solitary, in the confines of my apartment. However, I look at the comments on my music videos that I made, that I’m really proud of, that I was really happy to put into the world. I felt like, “I can get behind this.” And then to see almost these little support groups forming in the comment section of people saying, “Hey, I had a really rough day, but this song was helping me.” And someone else commenting on that like, “You can get through this. Stick with it.” There’s this whole corner of the world that’s so gentle and kind and tender towards one another and this music is resonating with them.

So much of this album is informed by interactions with loved ones in your life and the occasional ships-in-the-night random New Yorker. Throughout, you use people’s names and talk in concrete details. Has that always been the way that you translate experiences into music or did you hone that over years of writing songs?

I really think it’s the latter. When I was younger, I shied away from getting too specific. My poetic voice was definitely more distant. Maybe that’s just getting to know myself better, also not being afraid to really talk about my story. A lot of stuff has happened to me over the past few years that really pushed me to be thankful for my experiences and realize that those are my experiences alone. Really settling into this idea that everyone is an expert at something, and it’s their own life. To be OK with that and not feel like, “I have to be an expert at poetry. I have to be an expert at music.” I think I really grew up around a lot of virtuosity and simultaneously always felt the pressure and the need to push against being really skilled at an instrument in order to feel prepared to put myself on a stage. That’s always been a very push-pull relationship for me. I started to settle into the idea that, as a songwriter, none of that really matters.

Getting down to the specifics of citing people’s names felt at once embarrassing and too diaristic, but on the other hand, that’s just what I was experiencing. I think about some of the writers that I love and using specific, very colloquial speech and examples are something that I’ve always strived for. I’m working on how to bring very everyday experiences into light, because I’m feeling that all the time, but am I translating that into song?

I think sometimes there’s a pressure that something has to be broad for it to resonate, but you can also get there by really drilling down on specific experiences.

I think you can arrive at the same feelings that maybe more lofty writing and lofty prose can arrive at. You can still get at those feelings with talking about the stuff of everyday life. Talking about the pavement, talking about K-Mart, or whatever it is.

You’ve played in a wide array of types of bands and projects. Is there a musical influence that you think would surprise listeners?

When I was younger, a lot of the stuff that was influencing me was a lot of noise, which might surprise you based on the ambient quality of this record. Especially being in Providence — I went to RISD — there was a big noise scene there and the Fort Thunder scene. My taste tends to veer much harder than my expression. The things that a lot of people cite as clear influences were not really influences at all. Stuff like Black Dice or Lightning Bolt, those types of bands, are maybe just as much a part of my brain as more obvious influences like Roy Orbison, Laurie Anderson, and Velvet Underground. And there’s a lot of ‘90s pop, that’s something that I cannot get away from.

To go back to your earlier question, I think I was always afraid to talk about personal stuff because I was afraid of sounding like a confessional ‘90s songwriter with an acoustic guitar. That stereotype really scared me and then I realized that doesn’t have to be something I’m afraid of, especially if I’m talking about my own thing.

In the time since you had the experiences that are present on the record, those interactions have changed so much and are less plentiful. Has it been tough for you in terms of not having that same level of interaction with people in the last year?

It has been difficult. It’s weird, because the record talks about walking around alone and that was before I basically spent all of my time doing that. It’s always been a meditative space, but it’s usually been my way of processing my experiences with people. And I’m lucky, being in New York, you can strike up a conversation with anyone on any given day. One of my first coping mechanisms was birdwatching, which got me closer to nature, forgetting a little bit more about my ego and all those things. All the fears we were collectively feeling. Observing nature always helps me with that.

I don’t think that I will necessarily write another record the way that I wrote this one, where I’m walking around mining New York City for a quote here and a quote there. [laughs] I’m always writing down quotes. Like for instance, I was in the post office yesterday, and a woman went up to the post office clerk and said, “I’m sorry I’m taking so long. I don’t usually take care of this. My husband did, but he’s dead.” Just hearing people say things like that in plain English to a stranger, I just always find that so interesting. I always have my antennas up for sights or sounds or things like that.

So much of the indie music scene in New York seems so hubbed in Brooklyn, but you’ve spent most of your life in Manhattan. What is it about Manhattan life that keeps you there?

I’m a lifelong Upper Westsider. I know all my neighbors. I work at the farmer’s market. I have volunteered at some of the nursing homes nearby. I like being a part of a community and I like knowing that when I go to the farmer’s market on the weekend, a couple people heard my record. I do feel like I’m a member of the Brooklyn scene, but that’s not all I am. I think we all really need to make sure that we’re not getting too narrow in our focus, but to always be supporting the people around us.

Have you given much thought at this stage to how you want to take some of Phenomenal Nature and convey it in a live music space?

I’ve always been someone that likes to be really flexible with how music presents itself. The bones of this album are in the lyrics, and as long as the lyrics are there, I think the music can kind of sound like anything. I’m really compelled by a lot of artists who do things completely differently live than they might do them on a record. Why would we play live music to sound like a recording? It doesn’t really make sense to me. Music should be much more of a conversation between people playing together. I think I’d grow very quickly bored of trying to recreate something day in and day out just as it was recorded. I also could have made a completely different sounding record, but I made it with my friend Josh and we made it sound the way that it does.

When you look back at the stretch of time surrounding Phenomenal Nature, are there any specific milestones or benchmarks that you want to hit so you’ll know you’re satisfied?

I’m already so satisfied. I went into this record thinking I was going to quit the music business, so everything that happens from here on out is one big mystery cherry on top and I’m so curious what the next three-to-five years will bring. I have to approach it in the most open way possible, simply because my expectations are already blown out of the water. I’m excited to see where it goes.