Entertainment

What Female Pleasure On-Screen Tells Us About Ourselves

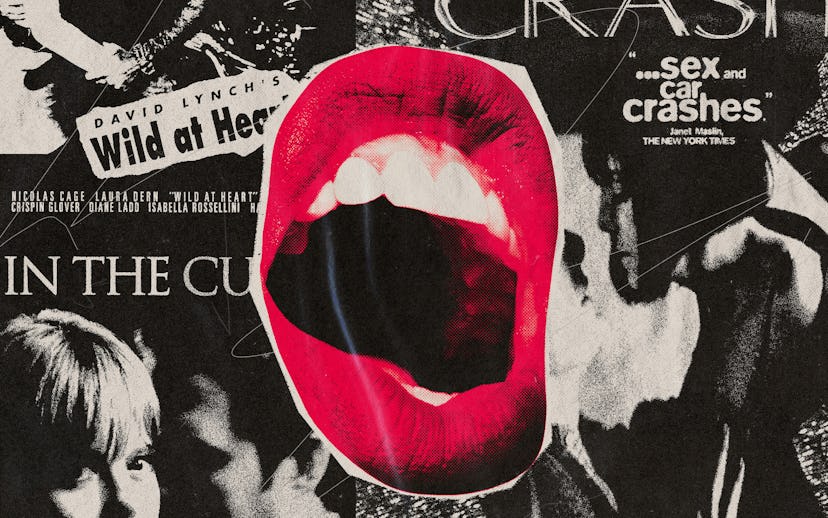

In a society that still fears the female orgasm, movies can fill in the gap.

“Moving images are surely the most powerful sex education most of us will ever receive,” film scholar Linda Williams explains in her comprehensive study of intimacy on film, Screening Sex. Even now, with online porn at our fingertips, this continues to be true — but we rarely mistake it for something real, even though the pleasures and positions are often achievable. And yet, it is film that we attach our sexual identities to. We want to see ourselves on-screen, perhaps more now than ever before, with an emphasis on film reflecting our truths, morals and identities back to us. So when we as children begin to model what adult life will be like in our minds, we look to cinema and popular culture to give us an idea of what dating, relationships and sex will look and feel like.

Realistic sexual representation on-screen can come from the strangest places. In Nicolas Roeg’s experimental thriller Don’t Look Now, Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie play a kind of sexually active married couple that was only able to emerge onscreen in the ‘70s after the removal of the Hayes Code. Amid the trauma of losing their daughter, the couple takes comfort in each other’s bodies, in a sex scene that is both tender and explicit, loving and somewhat graphic. We see both of them get off, holding each other during and after. Both partners are equally nude throughout the duration of the scene, and there’s a quiet beauty to their connection that touches both the heart and the libido.

In my first piece on the subject of sex on-screen for Bitch Media, my focus was on film as a form of sexual instruction. Specifically, I addressed the ways film was often inaccurate in its portrayal of sex, highlighting the way it is weighted towards the heterosexual, white male perspective. The priorities of cinema have largely been determined by what makes the intended audiences most comfortable, with that comfort being shaped by a society with a consistent fear of and disinterest in the female body and the methods that allow it to reach orgasm.

But as important as cinema can be as a method for cultural instruction, there’s a much simpler point about sex on screen that I forgot to make: sex scenes in movies are fun to watch. It’s especially thrilling to watch a woman reach orgasm. Even when they’re inaccurate, implausible and downright strange, nothing compares to the face of a woman in ecstasy. These scenes are just as pleasurable when they’re dangerous —sometimes even moreso. The pleasure in watching sex doesn’t begin and end with imagining the acts on-screen happening to us. Each scene carries within it a carnal truth, uninterested in the politics of taste or any moral objection.

To be a woman in the world is an undertaking all its own, with threats so frequent they’re almost mundane. In the films of David Lynch, female pleasure is a brave, rebellious act. His most notable films Mulholland Drive and Blue Velvet blend dark and light, pleasure and pain, fucking and death. Both the bright-eyed pollyanna and dark-haired vamp are drawn with empathy, resisting the urge to favor one over the other. Lynch’s women suffer, but his films never frame them as deserving of it, with small moments of tenderness and pleasure cutting through the pain whenever possible. As Dorothy Vallens, Isabella Rossellini plays a woman in trouble who struggles with conflicting feelings of fear and desire. One moment she’s a prisoner to her urges, caught up in her captor Frank Booth’s psychosexual games, and the next she’s defiant, making her would-be savior Jeffrey strip naked in front of her. At no point in the film do I ever want to be Dorothy, and yet I understand her and the way she fears the very things that turn her on.

But in one of Lynch’s films, pleasure isn’t a threat to its heroine, it’s her salvation. “Sometimes Sail, when we’re making love, you just about take me right over that rainbow,” Lula says excitedly to her lover in post-coital bliss. In Wild at Heart, Laura Dern plays Lula, who escapes from a domineering mother with her lover Sailor, a brutal young man in a snakeskin jacket with bedroom eyes and a devotion to Elvis Presley.

Nicolas Cage is undeniably sexy as Sailor, but his allure is all the more pronounced by his attentiveness in the bedroom. The sex scenes between the two are short, intense and frequent throughout the narrative. Lula always achieves orgasm, her moans vibrating through each sweaty, lustful scene. And then, she compliments his technique. “You are so aware of what goes on with me. I mean, you pay attention,” Lula tells Sailor with a smile. “And I swear baby, you got the sweetest cock. It’s like it’s talking to me when you’re inside. Like it’s got a little voice all its own. Oh, you get right in me.” The path before Sailor and Lula is a treacherous one, and they come out of it brutalized and traumatized. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t time for pleasure. And before the carnage, Lula has the best sex of her life. And we’re right there with her, imagining how it feels. We all want a lover like Sailor.

But sometimes pleasure comes not from a loving partner, but from someone who may chew you up and swallow you whole. In Jane Campion’s 2003 erotic thriller In the Cut, we are treated to scenes of undeniable female pleasure in the midst of unspeakable violence. Fear and arousal often go hand in hand, and for sexy English professor Frannie, the thrill is worth the risk. There’s a murderer on the loose, and he’s killing women all around her. And the man on the case is also Frannie’s number one suspect, the young and crass Detective Malloy. But Frannie still sleeps with him, unable to resist his coarse charms. Once Malloy eats her out, bringing her to orgasm, Frannie is possessed with newfound confidence. She asks him if an older woman taught him, and she’s right. Of course she is. The key to pleasuring women is the ability to take instruction. The clit is not a mystery, but a man has to be pointed in the right direction.

As a viewer, I find myself most drawn to erotic scenes where the male partner has a strange energy. Not the self-assured Michael Douglas type, oozing with traditional masculinity. For me, James Spader is the soft masculine ideal. In David Cronenberg’s erotic thriller Crash, Spader plays a man devoted to pleasuring his wife, touching her tenderly whenever he can. When he develops an erotic fixation on car crashes, he brings her with him into a strange sex cult. She likes when he pleasures other women, listening excitedly as he recounts his exploits to her. At night when they’re in bed alone, he fucks her as she looks elsewhere, imagining the pictures he paints in her head until she climaxes. His voice is a sultry whisper, speaking every word carefully, knowing that his words are essential to the sexual play. He deploys his quiet voice to a similar effect in Secretary as Mr. Grey, an authoritative Dom to his mousy employee, Lee. In one memorable scene, Lee masturbates in a bathroom stall while Grey tells her exactly what to eat, even specifying portion sizes. It is in that scene that Lee realizes how much she loves being told what to do, and the revelation causes a belated sexual awakening. The power imbalance between them is part of the thrill for her, despite the obvious moral objections to their relationship.

Sex on-screen is often morally murky and thus often incapable of being defined as liberation. But it can provide us with a form of release — much like the orgasm itself, there’s something relaxing about watching it. There is a poetry to our baser instincts, the rhythm of catch and release. The orgasm is not unlike the climax of a thrilling action sequence or the rush that comes when our hero has the villain caught, finally, with no way to escape. Society’s fear of the female orgasm lends to the excitement of seeing a woman on a large screen, mouth open, legs spread apart, pushing past her fears for one beautiful moment that, as Lula so eloquently put it, takes her “right over that rainbow.”

This article was originally published on