Entertainment

What Live Music Can Learn From The World's Biggest Virtual Pop Star

The future is Hatsune Miku.

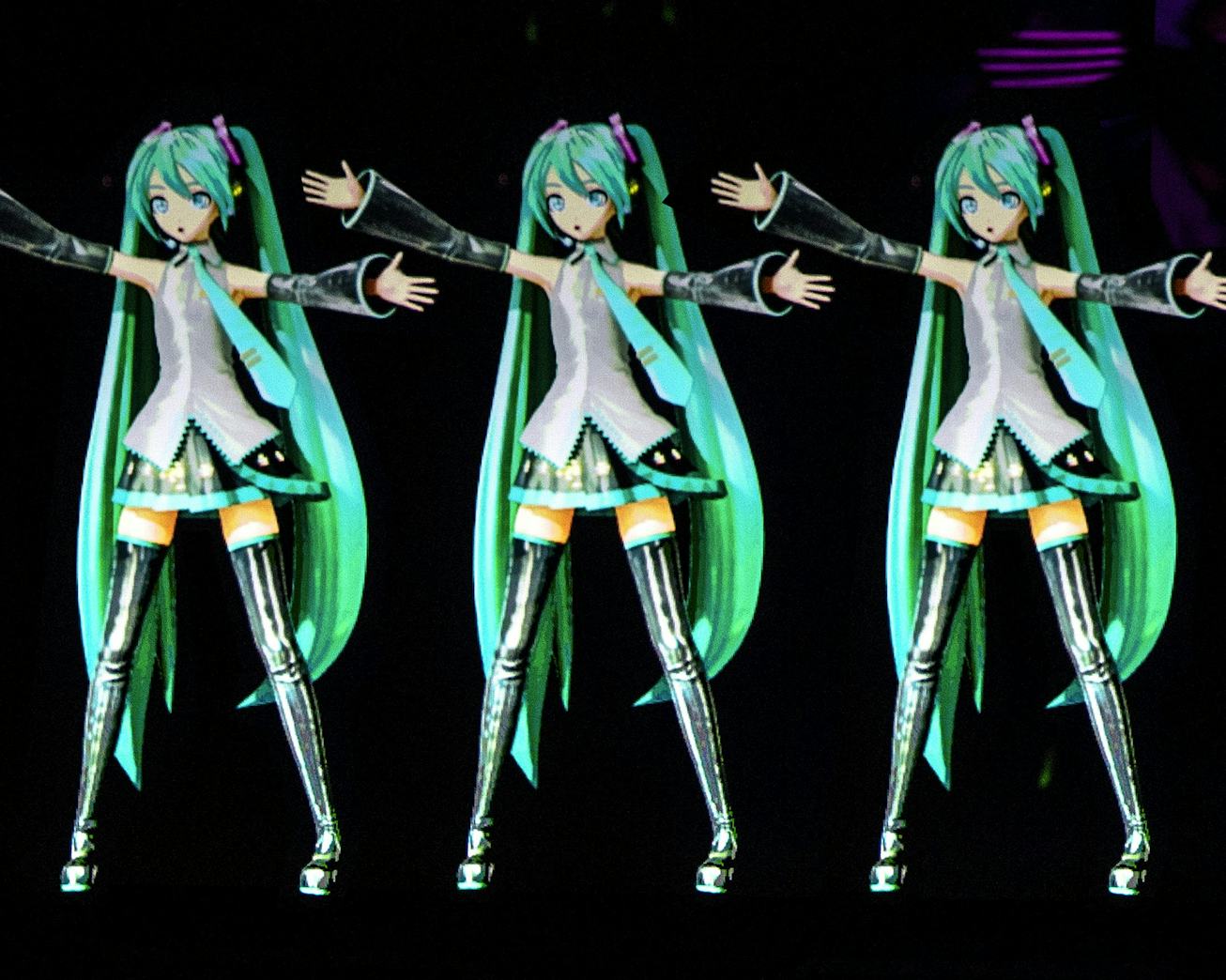

Hatsune Miku doesn’t drink in the roar of her audience, which she commands in the thousands. Miku can’t see the memorabilia, officially licensed or homemade, her devotees wear when they make the pilgrimage to their closest stadium. She will never be able to drive but she has a dedicated race car team. Though she’s been performing for over a decade, she never worries about her evolution in the public eye. Sixteen-year-old Miku isn’t your typical teen music prodigy. The teal-pigtailed wunderkind, whose name literally means “the first sound of the future,” is a virtual pop star created by Japanese music software company Crypton Future Media. This year, she was poised to make a splash on one of Western music’s biggest stages — Coachella 2020. (In the wake of Coachella’s postponement, the North American leg of the Miku Expo tour has also been rescheduled for the fall.)

At her crowd-sourced heart, Miku is a voicebank officially “fluent” in Japanese, English, and Mandarin Chinese. Creators of all skill levels can use her voice technology as an instrument by inputting their own lyrics and melody, which Miku then “sings.” Over the past decade, fans have turned Miku into a bona fide digital pop star: she has almost a million YouTube subscribers and, by one count, she’s the vocalist on at least 100,000 fan-created songs. The next logical step: stepping into the real world to grace her fans in the “flesh.”

Miku’s not the first virtual musician brought to life by projections. Gorillaz, the collaboration between musician Damon Albarn and artist Jamie Hewlett, performs as cartoon characters backed by live musicians. And the rising trend of “hologram technology,” a blanket phrase for all kinds of projections popularized when a Tupac facsimile performed at Coachella 2012, literally brings musicians back from the dead for morally dicey nostalgia.

But Miku stands apart from these other virtual figures. Apart from her voice, recorded during development by Japanese voice actress Saki Fujita, she is otherwise totally customizable. Everything else about her, from her image to her music, is built by her millions of adoring fans. As humanity hurtles messily into the 2020s — unsure when we’ll next go to a concert — she is paving the way for new conceptions of what modern live music and fandom can achieve, an unconventional pop star whose origin story unknowingly predicted many of the trends and trials the music industry faces today.

The VOCALOID software that birthed Hatsune Miku was Japanese conglomerate Yamaha’s early bet on the idea that human voices would one day be as much a part of any amateur musician’s toolbox as a drum sample kit. Crypton — a separate but close collaborator of Yamaha’s whose ventures include licensing sound effects to companies like SEGA and Nintendo — partnered with Yamaha to release the first Japanese-language VOCALOID voicebanks. In 2007, as part of the VOCALOID2 launch, Crypton released its own creation: Miku. She was originally marketed toward professional creators solely as an instrument, but early runaway popularity, helped by her anthropomorphization by Crypton-hired Japanese illustrator KEI Garou, spawned a thriving amateur creator market geared around VOCALOID personalities.

Miku rose to fame the way many do these days: by getting lucky on an emerging social platform. In 2007, as the Japanese video sharing website Nico Nico Douga took off among anime and manga fan communities, Miku ascended as an early meme idol, partly because of good timing. Though there are other characters populating the VOCALOID universe — like the blonde-haired twins Len and Rin Kagamine — Miku is far and away the most popular one.

Despite her origin as a music-making tool, many of Miku’s fans venerate her as a real pop idol. Destiny, a 19-year-old student, is a prototypical Miku fan who entered the fandom after falling down the YouTube rabbit hole of VOCALOID content, mostly reposts from Nico Nico Douga. From there, she followed Miku dramas made using MMD (MikuMikuDance), a free animation software that fans use to put VOCALOID characters into soap opera-like situations, and she began drawing Miku fanart. One of her pieces is currently the banner for Miku’s English-language Twitter profile.

“These personas may be marketing ploys but they are also bases for creators to bounce ideas off of,” Destiny says. Though she’s played Miku games and created music using the VOCALOID 3 engine, she keeps coming back to the fandom because of its endless wellspring of unique interpretations, "the collective passion [that] keeps [VOCALOID] alive,” she says.

Because Crypton grants fans the ability to use any of their characters' images in a non-commercial context (unlike other character-based corporations, like Disney), Miku’s persona can run the gamut from being bratty and materialistic (“World Is Mine”) to lamenting the loss of Japanese traditions (“Senbonzakura”). The sole caveat amounts as much to a morality clause on Crypton’s website, which asks creators to: “not distort, mutilate, modify or take other derogatory action in relation to the Characters that would be prejudicial to Crypton's honor or reputation.” With these restrictions, Miku remains in a suspended state of moe adolescence, a diva without the implied breakdowns and high maintenance.

Touring is a financial necessity for pop stars and their backers, and Miku is no exception. But how do you create a broadly appealing concert when each fan prefers their own customized version of her? Which of her infinite songs do you play? Which of her millions of costumes should she wear? Then there’s the much more technical challenge of taking a digital performer on the road. But in recent years, Crypton has gone full steam into the campaign, upping Miku’s profile to create what Guillaume Devigne, a member of Crypton’s overseas marketing team, calls “the story of Hatsune Miku.”

“How far can a virtual artist go?,” Devigne says over a recent Skype call, his French accent cutting crisply through the digital distance between Crypton’s headquarters in Sapporo to California. “Let's do all the things that regular artists do. Let's do TV, let's do festivals. To try to tick the checkbox of what actual artists do. She's in fashion magazines. She's collaborating and doing duets, all those things. Her story is made of all those performances she's done, and it's only that. She's not gonna get married, she's not gonna be in gossip newspapers. That’s purely the history of Hatsune Miku: everything she is as an artist.”

Like any accomplished diva, Miku has a residency: Magical Mirai in Japan, which since 2013 has been her annual showcase. But in 2014, Miku went international. She brought her American acolytes together at MikuExpo in New York and Los Angeles; she played The Late Show with David Letterman and opened for a leg of Lady Gaga’s artRAVE world tour. Two years later, she was her own headliner for a tour that, Devigne explains, “was kind of a test. We saw [the live promotion] was working. We decided to come back.”

Two years is the average gap between Miku international tours. According to Crypton, this isn’t because they’re trying to limit Miku’s performances — if anything, the company is doing everything it can to expand her live presence. But it took time for Crypton, a software company at heart, to make headway into the live music production world. Tour prep begins a year in advance to lock down venues, which was initially a much harder sell. When Crypton first put out feelers for a large-scale tour, “one hurdle was to find promoters who believed in the show,” he said. According to him, before 2014 Miku was an unknown variable outside of Japan; promoters didn’t recognize her or her potential commercial appeal. For her subsequent international tours, promoters came to Crypton with offers.

Now with several blockbuster tours under Crypton’s belt, the company has trusted touring staff and event production subcontractors in their international markets. Still, most touring musicians don’t need one to two 18-wheeler trailers brought over from Japan for their equipment, nor specific venues large enough to accommodate the screens and projectors that bring Miku, who is officially 5 feet, 2 inches tall, to life. (The dimensions of the screens are a trade secret.) Even if you’re in the nosebleeds, Miku moves with precise motion-captured choreography, her cerulean eyes scanning the crowd and crinkling in prerecorded pleasure.

"She's not gonna get married, she's not gonna be in gossip newspapers. That’s purely the history of Hatsune Miku: everything she is as an artist."

Like most pop stars, Miku rolls deep. But instead of wardrobe and beauty squads, she’s joined by a Japanese crew, including her band — MKP39, a rotating rock four-piece that backs all "live" performances. The most important aspect of the show is syncing the projector that beams out Miku’s image with the sound, a crucial symbiosis that’s monitored closely throughout the show.

Ryoji Sekimoto, a Crypton live event producer and music business advisor, has been a chief Miku producer since 2013. In an email conversation translated by Devigne’s colleague Riki Tsuji, Sekimoto recalls only one memorable live show mishap: “Due to an error in the sync system we performed an entire song without the characters on stage,” he said. But unlike human performers, should something go really awry Miku can always be rebooted, thanks to an at-the-ready duplicate system as backup.

Anamanaguchi, the band that brought chiptune music — music made using sound effects associated with old-school video games — out of the arcade and into the music listening mainstream got a front-row seat to orchestrating a Miku performance from scratch. Before opening for the North American leg of Miku Expo’s 2016 tour, the band worked with Crypton and SEGA to add their original song “Miku” to the set list. While most Miku songs are adapted for her live performances using existing fan-made choreography, the band got to conceptualize how Miku was going to perform their song.

Although Miku’s movements don’t have to obey the rules of physics, guitarist Ary Warnaar recalls that there was still a strict narrative to follow. “She’s not just a random avatar you can throw anything at,” he explains over email. “You’re not gonna see three copies of Miku on stage doing quadruple backflips in American flag bikinis, and then exploding into pieces anytime soon.” After deciding on their unique take on Miku’s dancing (influenced by AyaBambi videos), all that was left to do was actually perform their collaboration together on the road.

“Before going on tour with Miku, we always joked about her having an empty green room with like… a single bottle of champagne and one candle in it and no one is allowed in throughout the evening,” Warnaar jests, before emphasizing: “Everyone on Miku’s team is super kind and respectful, and passionate about putting on a good show. For being one of the most demanding productions I’ve ever seen, it was also one of the least chaotic. There were systems and roles in place that allowed for everything to run smoothly.”

Miku’s popularity — and people’s response to it — illuminate a lot of the contradictions that have always existed in pop culture. “I think the presence of digital avatars in the music world has created some interesting cultural mirrors,” Warnaar points out. “Like when people say it’s strange that Miku is a 16-year-old girl, as if Britney Spears wasn’t 16 when ‘...Baby One More Time’ came out, or Billie Eilish didn’t just turn 18 a few months ago. Or when people comment on Lil Miquela’s pics saying, ‘Why is this fake robot trying to secretly sell me shit,’ as if that’s not what the majority of your Instagram feed has become. It is all totally weird, but it’s an accurate reflection of our reality.”

“The industry has been treating real people as if they’re digital avatars with numbers floating above their heads for years,” he adds. “What has changed, clearly, are the fans, the creators, and the overall culture involved with digital avatars. All of which have been symbiotically evolving what a ‘pop music artist’ can look like.”

Miku’s promise is that every relationship she forms is genuine and unique. It is also what gives her and other virtual stars so much potential as an alternative form of celebrity. The volatile dynamics of stan culture can be tricky for stars constantly under a critical spotlight. Miku and other virtual idols offer an endless repository for that adoration in a way that organically embraces the uncanny public-private life of modern stardom.

As the music industry now reels from the shockwaves of coronavirus shutdowns, it’s worth examining what the industry can now learn from the world’s biggest virtual pop star. Pre-quarantine, at least one high-profile musician figured out one novel lesson; Grimes, too pregnant for an editorial shoot, utilized her digital avatar War Nymph to take her place. In our post-quarantine world, artists like Charli XCX, Timbaland, and Swizz Beatz have pivoted to online experiences (like the upcoming Square Garden festival to be held on Minecraft) — revealing the infinite possibilities the virtual world has to offer fandom and stars alike.

And as for Miku, who’s already there, her and Crypton’s eyes are still focused on the IRL stage. According to Devigne, “[Crypton’s] been talking about Coachella as long as I can remember,” in part because it helps legitimize a canonical version of Miku’s life. She’s a phenomenon born of the internet, but she inspires people to create and connect offline. Devigne’s voice over Skype rises in intensity when he posits, “Even those fans who can't go to Coachella, to know that Hatsune Miku went on that stage… It's not something that's gonna happen many times, it's just a one-time thing. The fact of knowing that she did that is important.”

Miku is now gearing up to undergo yet another evolution. Crypton itself appears to be moving away from Yamaha’s VOCALOID software, instead focusing on folding characters like Miku into its own proprietary vocal editor, Piapro Studio. More pop collaborations are in the works. Crypton released Miku’s English voicebank in 2013 — recorded, still, by the original Japanese voice actress — and her Chinese voicebank in 2017. This is Crypton’s long game, and Devigne wonders aloud, “A lot of the show is also a showcase for visual arts. The tours are also a way to promote that and make [fans] feel, oh, maybe if I write a song that could be played on that stage, that could be an incentive to start making music.”

For all of Miku’s international aspirations, she is still the most popular in her homeland of Japan, which, next summer, will host one of the world’s last true global spectacles, the Summer Olympics. Though there’s been no word about who’ll be performing during the opening ceremony, it wouldn’t be surprising if a certain pigtailed teen dropped in, performing for millions on a screen within a screen. Surely, by then, we will all already be used to it.