Fashion

For Gen Z, “What’s In My Bag” Content Has More Existential Meaning

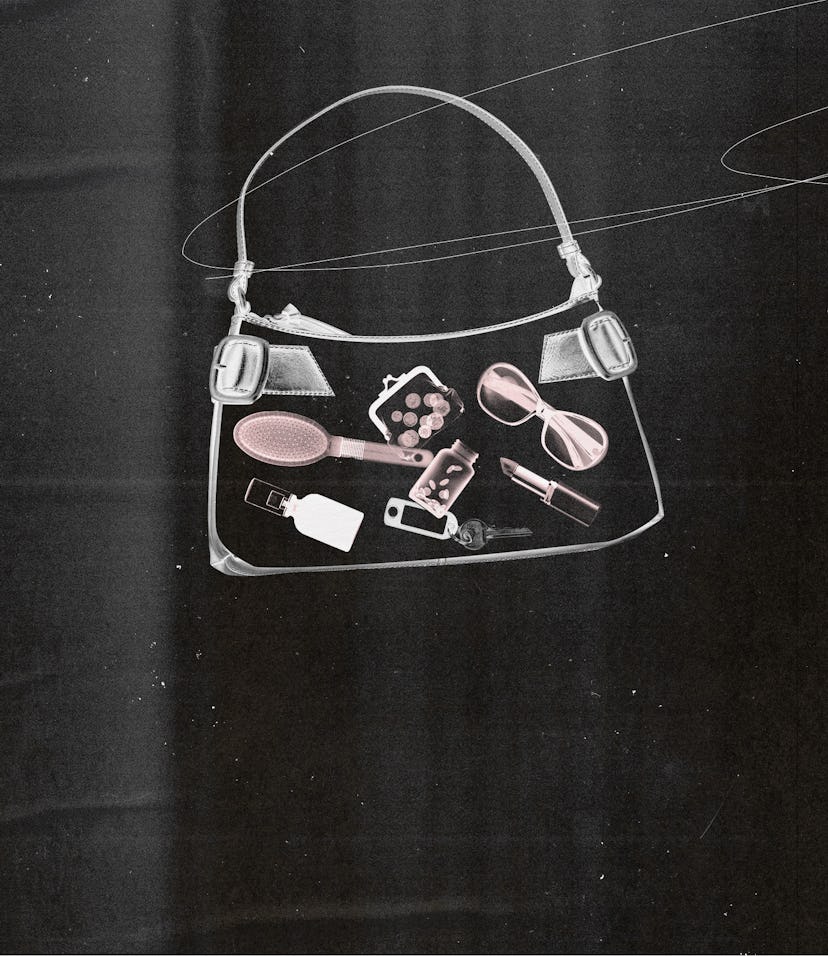

The voyeuristic content trend is less about shopping and more about identity than ever before.

For as long as women’s media has existed, there’s been a voyeuristic fascination with the things that celebrities personally use and carry around with them. Therefore the question of “what’s really in your bag?” has always been top of mind. In 1945 a magazine printed side-by-side images comparing the purse contents of child actress Margaret O'Brien and actress Maria Montez. By 2020, we would see Kylie Jenner pulling a Kylie Skin hand sanitizer out of her Birkin Bag on her YouTube channel. No matter when and how, it seems we never get tired of peaking into a celebrity’s purse. For seven years Vogue has even been running a YouTube series named “In The Bag” around the preoccupation. In late September, Sophia Richie posted her own “what’s in my bag video” on TikTok (featuring an EpiPen, adding to the video’s realness) and since, the format has taken off on TikTok. Now, #WhatsInMyBag has over 3 billion views on the app alone— and so it seems the “what’s in my bag” obsession has officially been embraced by new generation.

Yoona Bang, a 21-year-old artist in Dallas, has been experimenting with the what’s in my bag format as part of her cyberfeminist practice, on Instagram stories. “Having grown up in the 2010s watching beauty and lifestyle YouTubers post their #WhatsInMyBag videos, it really fascinated me to see the “what’s in my bag” phenomenon appear on my feed again, but this time in a memetic format that felt satirical of the original trend,” she tells NYLON. “These ‘what’s in my bag’ memes show cigarette butts, Calico Critters, rocks, and generally any items that would not typically appear in a ‘serious’ post.” In their artistic exploration, Bang’s “bag” contains an empty headstone, a rat, shells, moss, a spare tooth, and ibuprofen.

Bang believes the idea of knowing what’s in other people’s bags has enduring appeal due to capitalism. “We live in a society that supports the notion that we are what we consume,” they say. “So, knowing what is in someone’s bag feeds the parasocial feeling of ‘knowing’ who someone is [on social media].” The format has often been employed to prove relatability from celebrities, via detailing the quirky items kept deep in their purses. In 1995, actress Claire Danes revealed in a Seventeen interview that her backpack contained a tape of a song that her boyfriend, Ben Lee, wrote about her. In 2018, Tyra Banks told US Magazine that she carries sesame seeds and salt in her bag for when she’s at her favorite burger joint. Even Lana Condor joined the weird bag items club by saying she carried a small gnome in her purse in 2019.

While lip balms, wallets, keys, and practical items are usually safe bets to predict appearances from in a “what’s in my Baggu” TikTok compilation, there is a growing number of “trinket haul”videos where women proudly showcase the random items they carry in their purses. In one video, with the caption, “When he asks me what I bring to the table”, one creator pulls a lizard and four animal toys out of a bag. Another pulls out a series of prescription medications and there are multiple videos of creators showcasing that they only carry Sonny Angel dolls (a Gen Z favorite toy) inside their purses.

Fashion critic Rian Phin says that carrying these silly (if not impractical) items around is a way of establishing identity—like putting a keychain on your keys. “It's transforming something oriented around utility into a way to wield identity. I think it’s partially a result of content creating boom, where people are encouraged to brand themselves heavily,” she says. The videos work similarly to how people customize their online profiles or playlists. “They also serve as a response to misogynistic podcasts and the question of ‘what do women bring to the table?’,” says Phin. “It's a way of joking around the idea that you won't ‘bring anything’ to the table.”

For Phin —who keeps an Ami Colé lip gloss, Le Labo Myrrhe 55 fragrance, a Margiela PVC Wallet, clear hair elastics, a pen, matches, and an early 2000s mini-notebook in her bag— the appeal of the “what’s in my bag” trend for the next generation is the pursuit of uniqueness. “People are expected to detail their values and identities more and more specifically now. It’s keychains, to bag customizing, and even wearing worn in bags and clothes,” she says. “We want people's to perceive our identity as fleshed out as humanly possible, on sight.” Here to help us out is the rise of the bag accessorizing trends. Brands like Happy99 are releasing their own keychains, meanwhile while people are posting videos of ribbons tied onto their bag handles.

What’s in my bag culture has also permeated the fashion trend cycle itself. It’s not just the bag accessories—it’s also the bags themselves. Clear bags are having a major moment, putting the idea of “what’s in my bag” on full display. Kylie Jenner and Doja Cat were early proponents of the Coperni glass bag trend, while this year the Melissa x Telfar jelly bags offer the coolest (and less bulky) way to show off your purse’s content at all times. “Clear bags offer a way for people to express themselves and tell a bit of their story through what they carry,” says Raquel Scherer, brand director of Melissa. “It’s a canvas for personal style and creativity, which is at the heart of fashion.” In Scherer’s bag? “I usually have lip balm, Band-Aids, gummies, a pen, sparkling water, and concealer,” she says.

What we’re carrying in our bags can have different meanings for different individuals and even trend differently between generations. Your Prada purse may have a curated array of products that could be neatly compiled into a shopping listicle or your ribbon-adorned Baggu tote bag may only contain five Sonny Angel dolls, a lizard, and some antidepressants—that’s your choice. Either way, the fascination of peering into the bags of others, and in turn, having people look and judge us on the contents of our own, still remains.

This article was originally published on