Culture

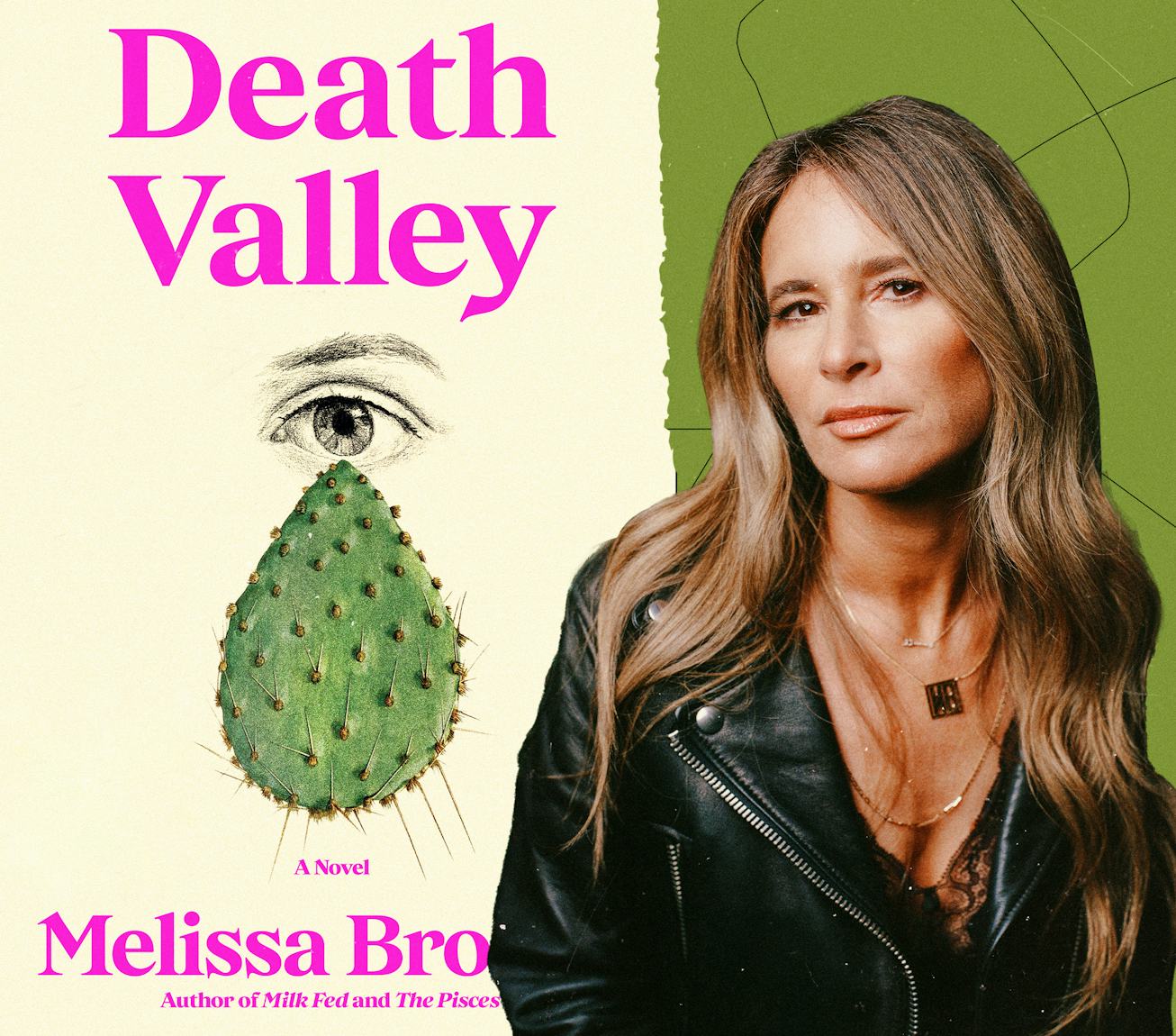

In Melissa Broder’s Death Valley, Grief Is A Desert

Melissa Broder on escape, anticipatory grief, and Death Valley.

The only thing less hospitable than a grieving mind is a desert. It doesn’t feel like life is able to survive, but by some miracle, it does — as long as you don’t get lost.

Melissa Broder’s third novel Death Valley is a surrealist story about anticipatory grief that is as wryly funny as it is moving. Broder curls moments of devastation softly towards moments of the mundane: It’s a book for those, who, in the wake of grief still have to do the pesky life housekeeping of making Amazon.com returns or pulling over at a Circle K to pee and buy beef jerky.

Death Valley follows an unnamed narrator in her 40s who is mucking through anticipatory grief in the wake of an accident that leaves her father in the ICU. She drives to Death Valley, leaving her chronically ill husband preoccupied with the business of living and a mother preoccupied with the errands of death (“I just remembered. I have to go to Home Depot and get a hose,” she shrieks during a phone call) at home in LA, so she can “figure out ‘the desert section’” of her next novel. She checks into a Best Western, briefly mourns the fact that the hotel no longer provides a free pen and notepad and tries to get to work – but why she has really come is to escape.

“If I’m honest, I came to escape a feeling — an attempt that’s already going poorly, because unfortunately I’ve brought myself with me, and I see, as the last pink light creeps out to infinity, that I am still the kind of person who makes another person’s coma all about me,” Broder writes.

Against her better judgment, the narrator goes hiking and finds herself inside of a magical cactus that lets her meet child versions of her father and husband. There’s no peyote involved; in fact, she is sober, and the only drug she’s on is the drug of grief. She gets lost on her way back to the car — where she has to physically find her way back, as well as face her grief, in a physical environment that’s as inhospitable as her mental one.

“Grief really can feel endless. Like nature, we're really not in control as much as we would like to be, and as much as we can think we are,” Broder tells NYLON. “I see the desert as really synonymous with the experience of grief.”

Though there are elements of magical realism, Death Valley is staunchly, comically grounded in reality: After all, what’s more real than overly vulnerable conversations with hotel front desk clerks, Reddit message board threads (which, in this novel, include r/onndeathanddying, r/botany, and r/beddeath), or having to pee while you’re lost in the desert?

“‘Pee is not a plot point,’ an editor once said to me. I disagree,” she writes. “There is never enough pee in novels. We pee as much as we eat and drink, and characters are always eating and drinking — but never peeing.”

Broder started writing Death Valley in the wake of her own father’s death. In 2020, her father was in an accident that landed him in the ICU. Broder and her family weren’t allowed to visit because of the pandemic, and Broder found herself frequently driving back and forth between her sister's house in Las Vegas and her home in Los Angeles, where she lives with her chronically ill husband. It was on one of these drives that the first line of the book came to her: “I pull into the desert town at sunset feeling empty.” (The gorgeous third line? “Help me not be empty,” I say to god in the Best Western parking lot.”)

From there, Broder conceived of a magic cactus where you could go and meet different loved ones at different stages of their lives, and that's where Death Valley was born. She didn’t know that it was going to be getting lost in the desert story until later, when she embarked on a desert recon trip for research for the novel and went for a walk at the tourist-heavy Zabriskie Point, where she got lost for 45 minutes — which unlocked the book’s final section.

NYLON spoke with Broder ahead of the release of Death Valley about anticipatory grief, getting lost in the desert with only a Coke Zero, and the surrealist elements of the novel ahead of its release.

Death Valley is available now from Scribner starting October 3.

I would love to hear more about why the desert is such a rich setting for this story.

I think because I conceived of the book originally when I was making that drive, it was always going to be a desert book. I'm not really a nature girl. I mean, I love nature, but I don't sleep in a tent in nature. I like to go home. So I did a lot of research. I read this book Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey three times, which I love. And then I read this book that I never, ever would've read if I hadn't been writing this book. It was a Desert Survival Skills by David Alloway, literally for military personnel. It's super hardcore. But that book actually helped me plot Death Valley a great deal because I learned about the hierarchy of wilderness needs, and I was like: Oh, she would need to build a fire if it's freezing. I knew she would have to drink water, but I got the timeline of how long you can survive without water, how long you can survive without food. The timeline then became very need-based in structuring the book.

I know you were only lost for 45 minutes, but what was the experience of being lost like for you?

He was very unforgiving in the Desert Survival Guide. He's like, these idiots go in and they only bring in their car and they go off-roading and don’t bring enough water. Every situation, I was like, I am that idiot. Number one: I didn't tell anyone where I was going. My husband was asleep in the motel. Number two: There was no service. And number three: I just thought it would be a little walk, and it's so touristy. All I had with me was Coke Zero, no water. And what I was doing was doing research, so I was on my phone in my Notes app the whole way down on the walk, hike, taking notes. And then when I got to the bottom, I looked up and I didn't know where the trail was.

The other thing I did wrong is, you're not supposed to panic. I panicked and I climbed up this rock face, and I got all cut up climbing. I had a lot of cuts and bruises, and I was pretty battered, which is also sort of how I got the idea that she was going to get injured. I didn't get as injured as she did. I didn't hurt my ankle or anything. I basically climbed up a rock face and slid a couple times and then got to a new landing and was crying, and then looked up and saw all the tourists. And I was like, thank you, God.

And that unlocked a kind of crucial plot point for you?

Once I got back to the car, I was like, oh, this is a gift. I was like, my Hell has become a gift. But it's also so funny. My husband does watch all those shows that are like, “I Should Be Dead” kind of shows. And they've been out on the boulder for four days, and meanwhile I'm out there for 45 minutes and crying. But I think that really brings me to the desert of grief – we are so powerless over it. Grief can feel endless and [similar to] nature, we're really not in control as much as we would like to be, and as much as we can think we are. I see the desert as really synonymous with the experience of grief.

A place like Death Valley is also very ripe for these kinds of new wave philosophies of healing and these spiritual gurus, which the narrator listens to a podcast from in the book. It’s a place where people flock for spiritual enlightenment.

There's a lot of woo in the desert.

This character is kind of anti-woo, but also is like, well, maybe there is something bigger than myself.

She's like, I need God. You'll try anything when you're desperate to heal or desperate to escape a feeling or yourself.

I'm curious about how surreal you decided to make it. There are some really surreal moments, but then it's also brutally grounded in reality.

I had a poetry teacher who said to me early on, your job as the writer is to teach the reader how to live in that world. Once you do that, you can really do anything. I feel like with Death Valley, that's what I did. For example, I knew it was going to be a Saguaro cactus. Well, in my research, I realized that Saguaros do not grow wild in California. Since it's a magical cactus, that shouldn't really matter. But I felt that I had to really ground it to make that fact part of the narrative. It's almost like I need to let the reader know, even if the reader doesn't even know that I know, but I think the reader can feel what the writer knows and that there's a good enough scaffolding to then have that departure into the surreal reality. You need a launching pad and rules of the world.

This book is really about a grief that's largely anticipatory. I'm curious why you wanted to explore that more: the thing before the thing, this ambiguous territory of grief.

When I was in that place, I was like, what is going on? I feel like my father has already died, but he's still alive. My friend Sarah, who I think I made Pickleball Sarah on Reddit in the book, her mom had just died, and she was like, “It's called anticipatory grief. Lean in. It's a real thing.” I had no idea that this existed. So that was what I did. I was really interested in this sort of state that I had no idea existed – and it can really apply to any kind of change.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.