Culture

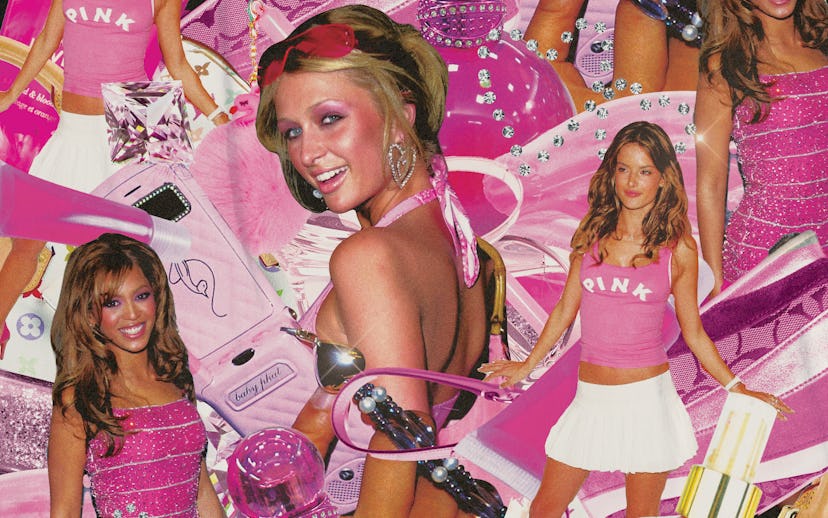

Hyperfemininity Isn’t A Trend — It’s A Movement

Hyperfemininity by girly girls, for girly girls.

I was born in 1993, which means I came of age right after the hyperfemininity of the ’90s and in the throes of Y2K, the golden age of all things glittery and pink. I went through puberty in the Limited Too dressing room and I am still chasing the high of coming home from school to watch new episodes of Lizzie McGuire and Phil of the Future.

For girly girls like me, it was paradise. I wore makeup to school every single day, I glued french manicure press-ons from the drugstore to my nails, I had every pair of neon sweatpants from Victoria’s Secret PINK, and I still have the magenta monogram Coach pochette that I begged my mother for when I graduated fifth grade. But in suburban New England, it also made me a pariah. At school my peers thought the height of fashion was a Tom Brady jersey or Jack Rogers slides, and names like bimbo and ditz followed me from middle school on, despite the fact that I carried straight A’s for most of my academic career.

I also experienced the dark underbelly of the hyperfemininity that marked the early aughts. I remember pining after the visible hip bones of my friends in their low-rise jeans and seeing magazine covers with young female celebs who were half my size being lambasted for their weight. I was in middle school the first time I went on a diet; in high school my friends and I went on Weight Watchers together, and by college, I had whittled my body down to a trim size 2 thanks to a diet of egg whites, Melba toast, plain yogurt, and Babybel cheese.

It’s taken me years to unpack the damage that those years did to my self-image. But it’s taken me just as long to realize a lot of the damage that came from the girly-girl naysayers; the teachers who chided me for carrying a purse to class, the friends who mocked my speech pattern with an accentuated valley girl lilt. The same way the magazine covers were telling me everything I wasn’t, these people were telling me everything I couldn’t be — namely, smart and girly; worthy and feminine.

Hyperfemininity for one, hyperfemininity for all

My hyperfeminine awakening came courtesy of the TikTok girlies, as the lingo goes. Like most people in their late 20s, I finally downloaded the app during the early days of lockdown. As my algorithm grew to know me better than I know myself, my For You Page became a collection of makeup tutorials, shopping hauls, and girls unapologetically being girls, gossiping about boys, decked out in pink and glitter.

In some ways, they looked a lot like the girls I grew up wanting to be: perfectly manicured, with all the latest beauty and fashion trends mastered — the kind of woman who always smells good. But in even more ways, these content creators looked nothing like the woman I grew up socialized to aspire to. They weren’t all white; they weren’t all skinny; they weren’t all blond with blue eyes. They were curvy; they were brown and Black; they were disabled; they were queer, trans, and nonbinary.

“Times have changed and everyone’s allowed in, so liking pink and lip gloss can be cool again,” says Becca Moore, a content creator who calls her brand “dumb blond satire.” Moore’s TikTok account has almost a million followers; you’ve probably seen her series on things “not for guys” in which she speaks directly to camera in front of a pink Notes app-like background, listing things that men shouldn’t have, like cars (they should run instead) and stores (they should hunt).

“From the modeling industry to Hollywood entertainment, the evolution of inclusion has definitely come a long way,” says Hikari Fleurr who creates hyperfeminine content that focuses on the Y2K and ’90s aesthetics. (Her tributes to films like The Cheetah Girls are what first came across my FYP, and I have been hooked ever since.) “Everyday girls with normal body types of all different shapes and sizes are posting content with confidence and encouraging other women to feel confident in their bodies as well. It makes me happy to see content like that because it provides the younger generation of girls relatable representation which many girls in my generation — a millennial — did not have growing up.”

And I know what she means. There’s a profound joy in watching women 10 or so years younger than me embracing all the fun and feminine indulgences of my youth without the toxic baggage that led to so much self-loathing and harm.

In the roughly two decades since the peak of the hyperfemininity of the ’90s and ‘00s, society has seen many a reckoning — about gender equity, body positivity, and race. Discourse about women’s bodies, while still far too common, has become less acceptable; at least some of the misogyny that permeated so much of the hyperfemininity of yore has been purged from polite society. Modern feminism, #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and other social movements have created indelible marks on the way we talk about inclusion and humanity that have shifted cultural conversations in entertainment and fashion.

And so a new generation of girly girls get to enjoy their lucite pumps in peace; but it’s also to their credit. Just as these content creators are coming of age in a different time than when Lindsay Lohan and Nicole Richie’s gaunt physiques graced magazine covers, they are actively building that better society from the inside. They’re not only riding on the inclusion that’s been built into society for them; they are expanding what it means to be a woman, to be a girly girl, to be feminine — and even to be radical; to be a feminist.

“I think that the Y2K and girly-girl aesthetic in 2022 is all about taking the best and most fun aspects of 2000s fashion and making it inclusive for everyone in a way it wasn’t back then, which, as a woman of color myself, is really great and encouraging to see,” says Amira Mohamed, who creates content about hyperfeminine fashion and films what she calls “princess-core, Y2K meets modern day Marie Antoinette,” under the username, @dreamingofdior. Mohamed’s feed is like a cotton candy-colored fantasy where her series on what your favorite hyperfeminine movies say about you will read you as well as any horoscope. “There are definitely more size-inclusive and diverse brands now offering girly clothing, as well as more influencers of all sizes and ethnicities embracing the aesthetic. In my opinion, this is great. The girly aesthetic is all about being unafraid to express yourself and dress how you love no matter what!”

In addition to size and racial inclusion, the hetero and cisnormativeness of the hyperfemininine and Y2K aesthetics are also a thing of the past.

Chrissy Chlapecka, a content creator with almost 5 million followers on TikTok, says their aesthetic is heavily influenced by the way she likes to express her queer femininity. “I think there is a lot of beauty in femininity in itself, but also so much beauty in how queer people express their own femininity and aesthetic,” they say. “It’s almost an art form of itself, coming from authenticity and self-acceptance.”

The TL;DR? You no longer have to be a Barbie girl to live in a Barbie world — you can be a Barbie he, she, or they and there’s a place for you at the hot pink table.

“Personally, I think there’s no denying that the hyperfeminine trend we’re all seeing come to fruition has its roots in drag and queer culture,” says Carmen Azzopardi, a content creator and publicist (she goes by PR Fairy) for the Australian-based clothing brand Dypsnea. “It’s enough sparkles to give anyone a migraine; full sass, full sequins and full sauce,” she says of Dyspnea’s aesthetic. “Our collections will always be inspired by the things we’re loving at the time, like Bridgerton, drag culture, and films like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, plus Paris Hilton. You can bet no matter what we design, there’s always a bit of Paris thrown in there.”

Not Like Other Girlbosses

Unfortunately, when it comes to belittling and looking down on hyperfemininity, the call is often coming from inside the house.

In 2013, Sheryl Sandberg released Lean In; I remember every girl in my Intro to Journalism class talking about it like it was the Bible. I immersed myself in the discourse being created by popular feminist authors who preached about being a working woman, labeling everything from Barbie dolls to strip clubs as toxic or antifeminist. It was the age of the girlboss, the perfect antidote to a childhood of being told we weren’t thin or pretty enough to be desirable. Girlbosses didn’t care about razor burn on our bikini lines or the best ways to please our men; girlbosses were above all that.

I fully leaned in when I started law school. I prided myself on being a “careerist b*tch” and I even had a membership at the Wing. I thought I had it all figured out.

Then I was diagnosed with endometriosis. Long hours in an office made me feel like I was dying; I was too sick to get through a full day of law school classes. I was in too much pain. And I found out quickly that the cult of girlboss wanted nothing to do with me. The women in my study group stopped sharing their notes with me; my female professors who were excited to mentor me began to tire of my need for accommodations and instead turned to reporting me to the dean for calling in sick. This movement, I realized, wasn’t pro-woman — it was pro a very specific kind of woman.

In the years since, we’ve watched the trope fall from grace — progressive feminists clearly appreciating the trend for nothing more than a repackaging of second-wave feminism rooted in derision for other women and racial and class ignorance.

Still, there were remnants of it well into the later 2010s; the no-makeup makeup of brands like Glossier borrowed their color palette from the girly-girl aesthetic, but their low-effort ethos was much more at home among the low-maintenance cool girls. The restrained chill of millennial pink screamed “not like other girls” — feminine but still somehow antithetical from the indulgent girliness of my youth. And while the low-maintenance cool girl lifestyle might promise absolution from a world in which the male gaze dictates our decisions, the content creators I spoke with said this freedom, too, comes with embracing hyperfemininity.

“I think hyperfemininity emphasizes women empowerment, which is what feminism stands for,” Fleurr says. “Thinking a woman is less intelligent or powerful just because of how girly they are is unfair. In my opinion, you can most certainly be feminine and be a feminist.”

Internalized misogyny is one hell of a drug. For a while, an entire faction of “feminism” was rooted in a deep hatred for hyperfemininity and bimbos. Pink’s “Stupid Girls,” while aging poorly, was an anthem of its time, a middle finger to the Paris Hiltons of the world. We were supposed to believe that calling other women brainless and ditzy was a form of radical advancement for gender equity. And while the tide is slowly turning toward an understanding that this, too, is misogyny, its repackaging as feminism is still pervasive.

“I think people see a hyperfeminine person and immediately believe they are a sex object. Not just men, but even those who claim themselves to be feminists,” Chlapecka says. “They believe that just because a man may ‘like’ what they see — hyperfem people — that it’s wrong or bad. What they don’t understand is that a man doesn’t give a sh*t what he sees, he will still act predatory and mistreat people regardless of what they are wearing.”

And some of the content creators I spoke with said, like me, they went through phases where they detached from the girly things they liked to earn the respect of their peers.

“I think that growing up we as young women are told that enjoying stereotypically girly things will make us be respected less by society and men,” Amira says. “But I feel like this is a form of misogyny in itself because we’re telling girls to give up things that they genuinely enjoy and make them happy for the sake of how others will perceive them, something that we never tell men to do. Men are allowed to keep loving seemingly frivolous and childish things well into adulthood like Star Wars, comic books, video games, etc., but grown women who admit to still enjoying Barbie films or loving rom-coms are mocked.”

Today’s generation of hyperfeminine content creators feels like a retort to the insulated privilege of Sheryl Sandberg disciples, of cool girls with low-maintenance ideals; a cathartic scream in response to all the women who proudly proclaimed they weren’t “like other girls.” They don’t care about being high maintenance, about being perceived as spoiled, or materialistic. And many of these creators are proudly feminist.

When I was growing up, celebrities shied away from publicly calling themselves a feminist — afraid the caustic associations with the title would make them less desirable or palatable for market consumption. But today’s girly girls are not only unafraid to call themselves feminists, they’re fully aware of the way chasms within feminism are in part to blame for the dispresect we’ve endured for so long.

“I never understood the concept of pushing hyperfeminine girls out of feminism,” Moore says. “Why are we polarizing ourselves? Makeup and glitter are fun. I think rejecting traditional girliness by making fun of them gives the vapid, ditzy stereotype more weight. No more ‘I’m not like other girls; I’m deep, I’m intellectual, I like sports and beer. I don’t even know how to do mascara.’ Stop. Being like other girls is amazing! Sports and beer are cool, books are cool, lip gloss and fake boobs are cool. Who cares, let’s be on each other’s team! Let girls do what they want; we earned it.”

The future is hyper-feminine

Every hyperfeminine creator has their own brand, their own aesthetic or bits that make their content unique. But the one throughline in all the most successful girly girls is an undeniable warmth and openness — that je ne sais quoi of the girl you run into in a bar bathroom who tells you your lip gloss looks great; the sweetness of when a girl tells you exactly where she got her top, and where to find a dupe, after a compliment.

“I love how confident girls on TikTok are,” Moore says. “They talk to the camera like they’re telling secrets, like they’re talking to an old friend. [They] aren’t hiding any secrets. They honestly don’t seem interested in impressing guys in the slightest. They’re putting bright eyeshadow on that’s three years old with a brush they found on the floor, and they’re telling us about it! I think girly girls are the funniest people alive.”

For all the factions of feminism and gender politics that look down on hyperfemininity, its most endearing trait might be that it looks down on no one. It doesn’t profess to be deeper or more evolved than anyone else’s ideal, but it also doesn’t capitulate to the notion that by indulging in stereotypically feminine things like gossip and shopping, we’re less than. The thesis isn’t: “Just because you like things pink and sparkly doesn’t make you a bimbo.” It’s: “We’re bimbos and we’re proud.”

The idea that we are conceding our power by embracing femininity is an outgrowth of two equally toxic societal trends: first the marketing of the aesthetic in the ’00s that drove women to eating disorders and clinical self loathing, and then the backlash to that by modern feminists who wrongly focused their animus on femininity itself, and not the pop culture machine that turned it into a weapon against young womens’ self-esteem. Today’s hyperfemininity correctly appreciates that low-rise miniskirts and pink pumps were never the enemy to begin with. Ridiculing stereotypically feminine things never liberated anyone — it denigrated us all and created a caste system that did the patriarchy’s dirty work. It further perpetuated the lie that to be feminine is to be weak and vapid. And what could be less feminist than that?

“I think this ‘current trend’ of hyperfemininity isn’t just a trend; it’s an overall acceptance of oneself,” Chlapecka says. “It’s not just about crop tops and miniskirts — which are wonderful and so much fun — it’s about self love and inclusion and loving ourselves. [We] know we have each other’s backs, unlike the early ’00s.”

Perhaps the most feminist aspect of this iteration of hyperfemininity is the ownership of the aesthetic. This is not being churned out by Disney studio executives to sell to pre-pubescent girls; it’s not being peddled to women by modeling agencies or casting directors as a means to sell dieting. This is hyperfemininity by and for girly girls.It’s as unapologetically vapid as it is radical — it is pro-woman, pro-inclusion, and most importantly, pro-pink.

This article was originally published on