Culture

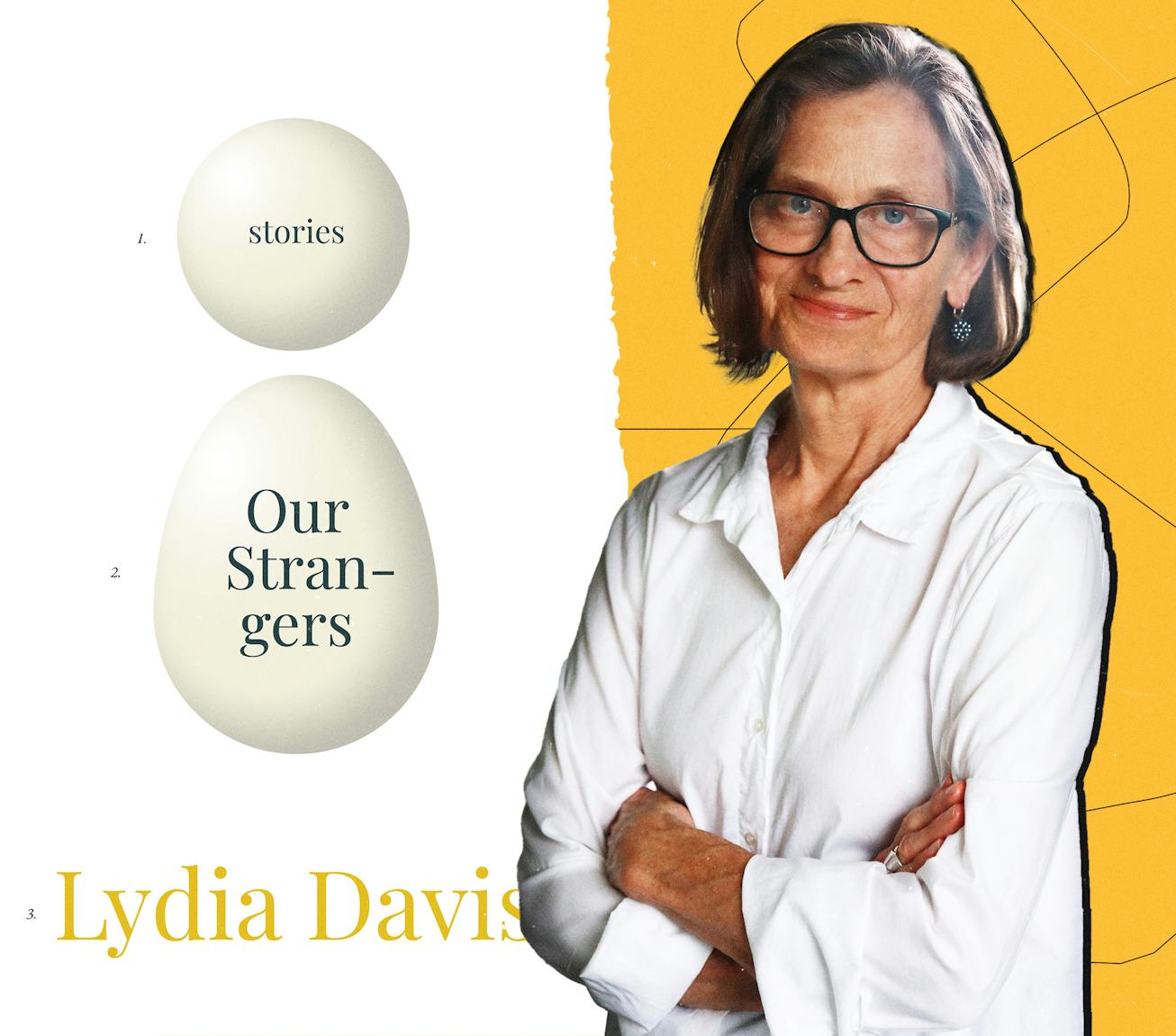

The Careful Contemplation Of Lydia Davis

Lydia Davis on Our Strangers, aging, and misunderstandings.

For Lydia Davis, nothing is wasted. Her short stories may sometimes include only a title and a single sentence, but for a master of economy, everything counts.

Davis’ fat, coral-colored The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, which was released in 2010, has beautifully chronicled her stories from 1986 to 2007 for a new generation. In the last two years, Davis has published two books of collected essays — but this month marks the arrival of Our Strangers, her first new short story collection in a decade.

Davis’ stories are treasures of observation. Using a notebook, she notes things that are interesting to her: whether it’s a conversation she overhears, a person she sees, or a fleeting thought. Later, she may or may not turn her observations into stories, expanding and concising them into bite-size meditations that are often about the foolishness of humanity. Her work has a grounding, anesthetizing effect for the reader. A Lydia Davis story is the best bite on the plate. What Davis finds fascinating, whether it be negligible claims to fame, the word for “egg” in Dutch, or a piece of mail mistaken for a white butterfly, are tiny worlds of their own.

In Our Strangers, one thing she finds fascinating is aging; she unintentionally includes at least three stories explicitly on the topic in the collection. “Aging,” for example, is about a woman in her 50s who counts all the things going a little bit wrong with her body, while “Fear of Aging,” simply reads: “At twenty-eight, she longs to be twenty-five again.” Aging is something that Davis, now in her 70s, says she doesn’t feel depressed about. Instead, she is curious.

“It's such an odd thing to die,” Davis says. “I know that's an odd way to put it, but we live such full lives and we develop ourselves so richly and have relationships, have thoughts, mature, change, so much goes on. And then for that all to be just cut down, finished, boom, it strikes me as very odd. Anything else that you develop, like a piece of artwork or the building or a field, you develop it and it remains. But people are developed so intensively and then just gone.”

NYLON spoke with Davis ahead of the book’s release about gleeful misunderstandings and how her sympathy for humanity keeps growing.

Where did this collection begin for you?

There are 10 years worth of stories that I've either written or rediscovered or returned to and revised. Because in those 10 years, I published two books of essays, so all my major efforts were concentrated on those. Meanwhile, the stories accumulate. That's somewhat the way each collection evolved, that I would write or finish a story and put it in a folder, and then after some time I would look at the folder and say, “That's getting kind of fat. I bet there's enough for a book.” That's what happened this time. I rounded up all the possible stories and put them in a kind of order and sent them off to my agent.

Do you have a favorite story?

That's a really tough question because there are so many. I haven't really done a proper count, but I've read other people's count is 148 or 143 stories. I think there's one about turnips, which is an unlikely one. That just tickles me because it comes from actual material, say 150 years ago or more, when people around where I live grew turnips and they actually were a very useful crop for trading for shoes or clothing or sugar, or you could use your turnips for any number of things. So I like that one.

There's another one called “The Stages of Womanhood,” which is based on a belief in the different stages that a woman goes through as she goes through reproductive ages and then goes beyond them. It's kind of weird and interesting to me: The woman contemplating how she's not going through the stages properly, so I like that one.

So much of your work feels very observational. How do you know that you want to write a story about something that you overhear or notice?

I do tend to write down absolutely anything that interests me. I don't write down things that don't interest me. I'm not dutiful about that. So I write down things that interest me, and I write them either in a notebook or just on a piece of paper. Anything that interests me is a good starting point for a possible story. Some are just too slight to make it into print. They may be whimsical or curious, odd, but they just don't have enough substance. So they just remain sort of observations. But others that I think have another dimension, have a certain richness. I think, okay, this can live on its own. It can survive. So then I work on it. Even the very shortest stories of a few lines I work on to get the wording exactly right. That makes a huge difference in the effect of it. And I do keep notebooks, so I can always go back to a notebook from an earlier year and just read through it and see if I come upon something that still strikes me as interesting and rich, see if I can take it out of the notebook and do something with it.

You're so interested in the ways people misunderstand each other, and you find humor in that. That feels like a very sympathetic view of humans. Do you find humanity sympathetic or charming?

Oh, yeah. I used to have a little more judgmental attitude towards people when I was younger. Over time, I think you just learn much more about human frailty and how hard people try and how difficult life is for a lot of people. I have more and more sympathy as the years go by for almost everyone. I won't say everyone — certain people in positions of power and certain politicians, it's hard to be sympathetic — but for a lot of other people, I'm very sympathetic and we do try hard to understand each other. It is often amusing when we get the words wrong and sometimes react very emotionally to something, but actually we've misunderstood it, and no harm was really intended.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.