Cuture

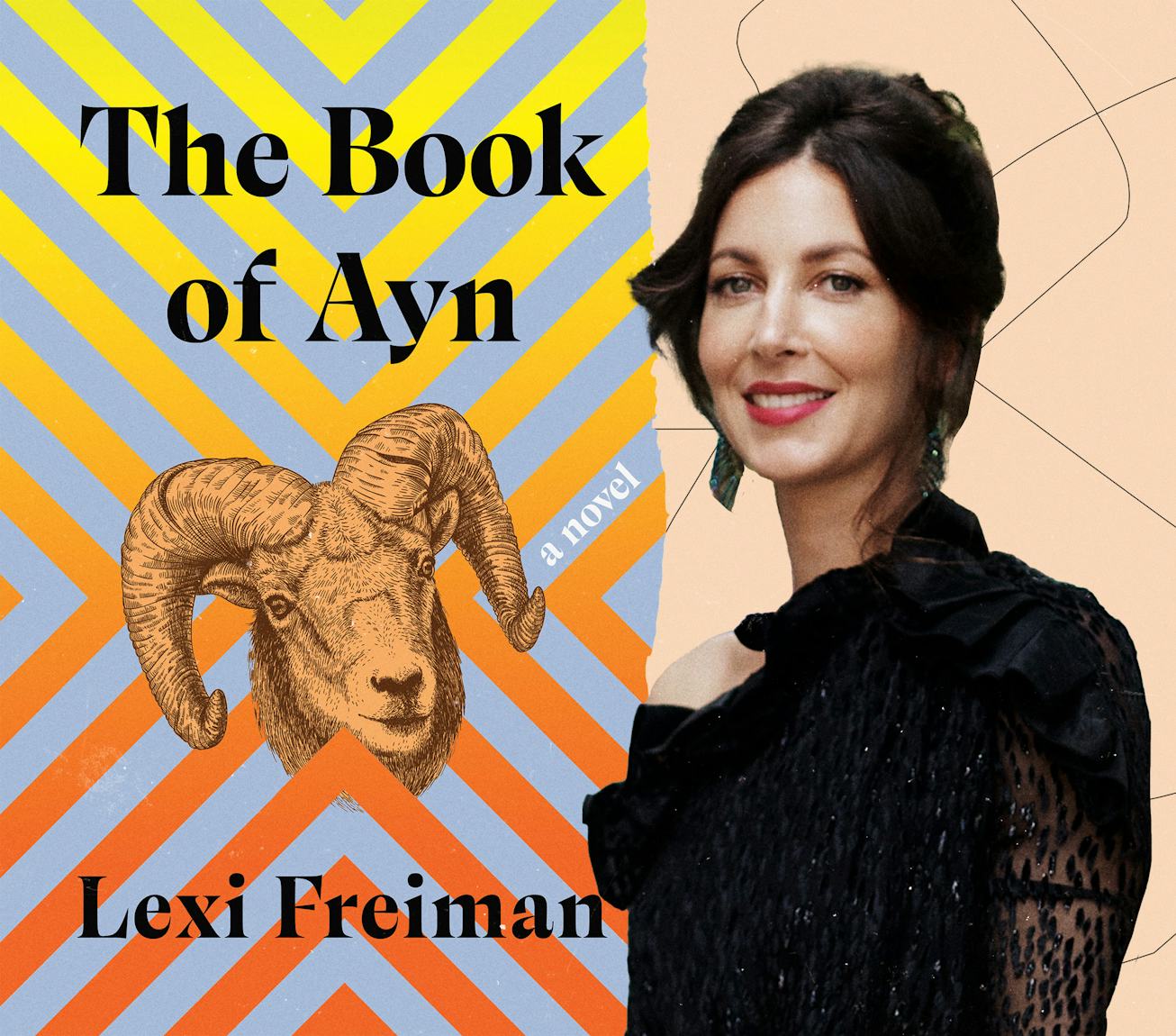

The Book Of Ayn, An Audacious Satire For The Modern World

In Lexi Freiman’s The Book of Ayn, a canceled writer embarks on an absurd, Ayn-Rand-fueled odyssey.

When you think of authors who define the millennial experience, Ayn Rand probably isn’t the first name to come to mind — but after reading Lexi Freiman’s wickedly funny second novel, The Book of Ayn, you’ll wonder why you didn’t connect the two before. The rollicking satire follows the misadventures of Anna, a 39-year-old author canceled by the New York Times for writing a “classist” novel about the opioid epidemic that punched down in a failed attempt at contrarian humor. Disoriented by her cancellation, Anna desperately searches for a new worldview. She finds it, surprisingly, in the writings of controversial objectivist philosopher Ayn Rand.

The Book of Ayn digs into the nuance of Rand’s oeuvre, avoiding being overtly critical or sympathetic but instead leaving space for the reader to consider each idea with the same open-minded, occasionally conflicted attitude as Anna — for example, when she struggles to agree with Rand’s anti-altruism sentiments during an awkward metro ride. “Everyone in my car was homeless, and I felt paranoid that they could somehow see the libertarianism on my face; feel it emanating from my self-serving pores,” she frets. Such moments of dissonance are frequent as Rand’s ideas come up against the realities of the 21st century, often to humorous effect.

“Obviously, there are lots of bad, simplistic ideas in there,” Freiman says of Rand’s controversial text The Virtue of Selfishness. “But then there are some fun, audacious ones.”

It isn’t long before Anna is hawking Rand’s ideas on extreme capitalism and radical selfishness to confused stoner podcasters at parties, her hot-and-cold friend Vivian (who is too wrapped up in her imaginary illness to sympathize), and essentially anyone else who will listen. She’s even commissioned to write a TV show about the “misunderstood” Russian thinker, prompting her to move from New York to Los Angeles — a city mired in Rand’s philosophies. During her tumultuous time in L.A., Anna witnesses firsthand the effects of unregulated capitalism (working the world’s worst dog-walking gig) and unlimited selfishness (living with a micro-content creator who refuses to flush the toilet). Disillusioned with Rand, she heads to a commune on the Greek island of Lesbos for a workshop on ego death — but the ensuing journey to the center of herself may be more than she can handle.

In a particularly bleak moment, Anna watches the commune’s popular group dance together while she stands apart, triggering a troubling revelation about her lifelong contrarianism. “Dancing would have felt so good,” Freiman writes. “And then I was sadder; wondering if I’d mistaken a life of refusal — to conform, to fit in, to disappear — for that feeling of aliveness.”

Freiman’s sharp new novel puts modern life under the microscope, satirizing everything from cancel culture and cringey hookups to misguided meaning quests and ridiculous content creators. Beneath the book’s surface-level hilarity, its eccentric cast of supporting characters add surprising emotional depth to Anna’s story. Her wealthy father and new age mother pester her to have children now that her career is over; her dates insist on showing her YouTube compilations of dad fails and Tom Cruise acting in lieu of conversation; the only person who truly comforts her in her post-cancellation spiral is Magda, a Hungarian refugee dying of stage 4 cancer.

No matter where she goes, Anna can’t quite find what she’s looking for. Her series of troubled encounters with younger men — a parallel to the older-woman-younger-man relationships that fill Rand’s writings and personal life — belie fears of aging, mortality, and maternity that become one of the novel’s most poignant plot threads. While Anna’s lack of self-awareness is easy to laugh at, her story draws tears, too. The Book of Ayn centers on Anna’s humanity, highlighting the complexity of the person behind the bad takes and contrarian cracks.

NYLON caught up with Freiman ahead of the book’s release to talk about bringing Rand into the 21st century, satirizing cancel culture, and conceptualizing Anna’s arc.

Did your writing process differ from how you approached your first project, Inappropriation, now that you had that novel out in the world?

After a first book is published, it's pretty normal to have a bit of a slump, which I think I experienced after publishing [2018’s Inappropriation]. You think your whole life will transform, and of course it doesn't. So I was a little depressed, and I was looking for another topic, and I found Ayn Rand. The approach was a little different because I felt like I needed to research and read a lot about her in order to know what I wanted to say. With the first book, you feel like you’re writing this thing in obscurity, so you can have all these wild fantasies about how it will be received. Then, with the second book, you become a realist — or worse, a nihilist. I think this whole dialogue has been like “OK, whatever, there’s a book, and another book, and life will just go on.” In terms of process, I’m just writing every day and then editing. I’ve probably written this book seven times and erased those copies. It takes a bit of time.

I can imagine. I do want to probe the Ayn Rand thing — why her? What led you to take her ideologies and connect them to the selfishness of contemporary culture, especially in the L.A. section of the book?

I think I was interested in her because she’s so despised, particularly on the left, and I needed to know why she was so bad. I had to see it for myself. But I found reading The Virtue of Selfishness kind of fun. Obviously, there are lots of bad, simplistic ideas in there. But then there are some fun, audacious ones. I felt like there was a way of mapping some of them [politically] — like, the right is this more selfish, narcissistic ideology, and on the left, it’s more of this virtuous, altruistic ideology. I was interested in exploring that through the lens of Ayn Rand. For me, it’s never interesting just to say, “Oh, this side is wrong and stupid” and to make fun of them. It’s more interesting to find the dialectical relationship between the two sides, and I felt like Ayn Rand would be an interesting way to do that.

I’m always looking for the person who everyone else disagrees with and trying to see the place that I might agree with them. The harder, less fun work is then going back and looking at the things I disagree with, and even trying to make them also in some way feel like there’s some validity there. So, some part of it is fun, and more organic to my personality. And another part is the hard work of “I want to write something that has taken everything into account.” It’s deeper than just a kind of knee-jerk, reactive response.

“I’m always looking for the person who everyone else disagrees with and trying to see the place that I might agree with them.”

That definitely comes through in the novel — you present all sides of every issue you tackle, like the subject of cancel culture. The concept of writing a satire about cancel culture almost feels like something that could easily get you canceled because it’s such a hot-button topic. I’m curious if there was any apprehension about broaching the subject?

Oh, God, yes. For sure. When I’m starting a book, often it starts with this kernel of rage or frustration. That’s the driving force to write. Usually the first draft is bad, because it’s too much of that. It gets better as you calm down and look at all sides. In the beginning, I’m like, “I don’t care what happens.” If I have to shill these books off the side of the street, in Times Square, then that’s what I’ll do. But then as you go on, you start to get more nervous about the possibility of really getting canceled, or just pissing off the wrong people, you know? Or somehow not getting it right, in the sense that you’re pissing off everyone, basically. But I personally like writing satire. The thing I’m trying to do is to say something that feels true to me, and if that means that I’m going to offend a few people, then that’s OK.

I think the work that’s too safe is less interesting, and I don’t want to write that stuff. It’s a bit of a risk, and I’m willing to take it because that’s the kind of thing that interests me as a writer. I feel lucky, because since I started writing the book several years ago, I feel like the culture has changed a bit. There’s much more openness to there being a satire about cancel culture. I feel like a couple of years ago, this would have been a much riskier proposition. I did get some feedback from people who were like “I don’t know, are you sure you want to do this?” Then the life-cycle of cancel culture feels like it’s moving into another stage. People seem quite fatigued with it now. A lot of people, not everyone.

I want to talk about Anna. She’s such an interesting protagonist. Like some real-life people who have been canceled, she’s really struggling with the way that she deals with life not being successful anymore — not being able to always joke about things the way she used to. But by the novel’s second half, she’s also trying to figure out all this deeper stuff about her past and her brother’s passing. How did you conceptualize her arc over the course of the novel? Did you ever have trouble deciding how much you wanted the audience to root for her and her struggles versus holding her accountable?

A little bit. That’s the thing with writing a satire. The trap you don't want to get stuck in is that you write a character who’s just a mouthpiece for all the things you think are wrong with the culture, and they don’t have their own biases and flaws. It’s a balancing act between having them express the things about the culture that are frustrating you, but then also having them be a complex enough person that the reader can see where they get stuck. At the same time, I don’t want to write a moralistic tale about a person who is an edgelord, who then is redeemed by her suffering. That’s the kind of story that, personally, I’m not that interested in — because I don’t really believe that’s how life is.

People can have learning moments, but I don’t think they change. I don’t think they transform drastically. That’s a Hollywood myth. I was trying to have some growth, and I wanted her obviously to feel defeated — to feel like she f*cked up — and have an experience that was very different to her exciting obsession with Ayn Rand. But then at the same time, I didn’t want that to become the thing that saves her or makes her transform because then you attribute too much to that ideology. And ultimately, the idea [of the novel] is that all ideologies are a problem if you try to live by them in a way that is absolute.

Another part of the novel that I found really interesting with Anna was her confrontation with aging and relationships. She’s getting into all these awkward, difficult encounters or relationships with younger men, and she’s also told she’s prematurely perimenopausal. Can you tell me more about writing that side of Anna’s arc and why it felt important to include? Especially as this is very much a millennial journey of self-discovery.

I feel like a lot of millennials in particular are making unconventional choices in terms of relationships and marriage — having children, not having children, freezing eggs, doing it on your own versus with a partner. I wanted this to be a character who is grappling with all that, but also, her contrarian nature makes her not want to do what everyone’s doing. But then, there’s part of her that wants, obviously, love and maybe something like a family or just a connection that’s deeper than sex. And as a woman who’s pushing 40, asking: “What is it like? What does it mean to have these empty sexual experiences with people?” I was really interested in the dynamic between younger men and older women because there’s something about that relationship — there’s a fetish aspect there, as mild as it might be.

As women get older, there’s an anxiety that then we’re not as attractive to younger men because men want younger women. But then there is this nice fetish thing — older women get to be objectified again, because younger men desire you because you’re older, and they desire things about you that often are not purely physical: your sense of self-possession or the experiences you’ve had in the world. It becomes a sexual currency. I find that interesting in the sense of the transactional nature of sex, and Ayn Rand talked about that a lot. Also, in the shadow of an older woman and a younger man is the idea of an older man and a younger woman, and the power imbalance. How does that map onto the reverse? All of that was interesting to me as minor, taboo stuff.

“All ideologies are a problem if you try to live by them in a way that is absolute.”

Besides Anna, were there any other characters in the book that you really had fun writing?

I really enjoyed writing Baby, because it’s fun to write someone whose first language is not English, but who’s really smart and has a really interesting mind. The way they think in English is fun. They use words that don’t quite mean what they think they mean. To me, that’s good comedy. And I liked writing some of those outrageous sex scenes. Finding the funny parts of sex, I think, is quite fun. Big Boy was fun to write because I was thinking a little bit about my friend. Maybe Vivian as well. I think. She’s an amalgam of a few different friends of mine. Putting some of her bizarre ideas into dialogue was fun for me — making that character make sense. It’s a fun challenge to have characters who are quite eccentric and who think quite extreme things, but still you make them feel real and cohesive.

Beyond The Book of Ayn, do you have any idea what you might want to satirize next? Or do you see yourself taking a break from satire or writing something completely different?

I don’t know. I left the U.S. a couple of years ago, and I spent some time in Europe, and I started to think “Oh, God, I don't want to write more satire of American culture war stuff” — because it means I have to keep up with that stuff. When I was in Europe, I was just like, “Oh, that’s right. There’s a whole rest of the world that doesn’t care about this stuff.” And it was such a nice break from the outrage news cycle. I did get interested in a hilarious topic, mental health, which of course is going to crack everyone up. I’m sure it’ll be a satire. I don’t know if I can do anything else. I don’t get as excited about anything else, and if I’m not excited, then I’m not going to take the time to write a whole book.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on