Culture

Desperation And Healing In The Burden Of Joy

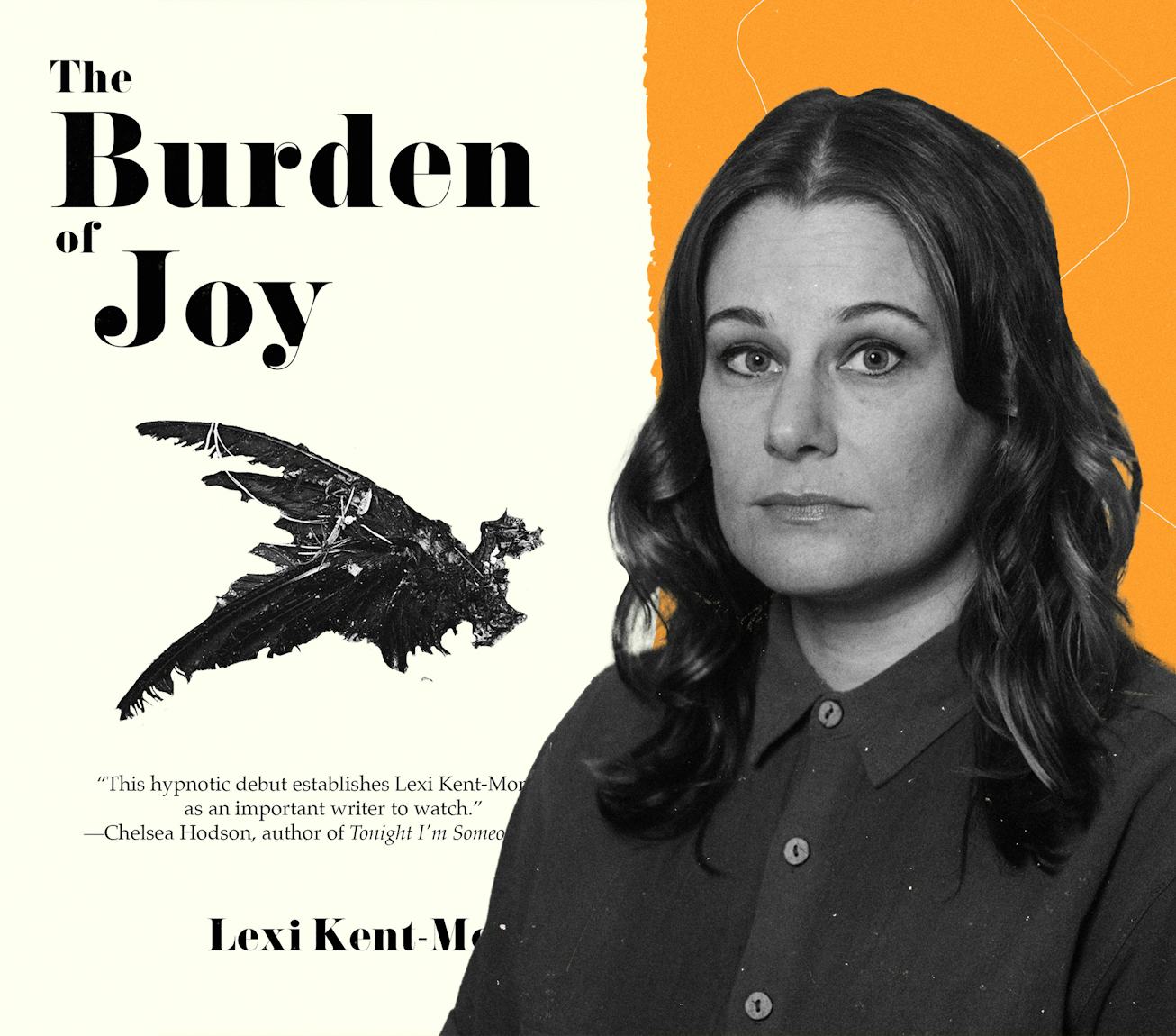

The Burden of Joy is your new favorite book about a woman alone and losing her mind.

After Lexi Kent-Monning’s husband left her to join a Big Sur commune, she began to write. She wrote because it’s what she’s always done, and she wrote to try to understand the fragments of her life. She didn’t set out to write a book — until she realized she already kind of had one.

Now, The Burden of Joy, her gutting and seductive debut novel, is out this month from Rejection Letters. The novel follows Lexi, who has to pick up the pieces in her life after her husband Daniel’s sudden departure blows it up. The plot is loose; the prose is tight; and Kent-Monning beautifully captures how emotional and physical wreckage weighs heavy on a spirit and body.

The novel is a cartography of loneliness traced in lost hair and weight, and even pigment: “My natural hair color, red, had begun to feel like a lie,” she writes before dyeing her hair blonde.

“My favorite genre is women who are alone and losing their mind,” Kent-Monning tells me on Halloween. She’s video chatting from her Greenpoint apartment, where every visible wall is covered in artwork: prints of reclining, tired nude women by Frances Redlich that she obsessively stalked the Dobbins Co-Op Instagram to snag, as well as a commission by painter Lauren Orscheln.

When I ask her about the art, she tells me they’re her most treasured items. Her apartment is a space that is all her own, which is very different from the space she created for her husband with careful, selfless-to-the-point-of-self-sabotage devotion.

The novel is a cartography of loneliness traced in lost hair and weight, and even pigment.

“Within two hours of meeting my ex-husband, I was sewing a hole in his pants. I told this story for 12 years. I wore it like a crown,” she writes. “I wanted everyone to hear the sweetness of when we met and he needed something and my helping hands were doing it for him before we even knew each other’s last names.”

One of the most poignant psychological throughlines of the book is Lexi’s role as a caregiver, one who obfuscates her own desires. It’s something she only realized through writing.

“Therapy is my favorite writing tool,” Kent-Monning says. “I can't believe I didn't ever see that about myself. It was through edits a few drafts in and therapy too, where I was starting to recognize that. Once I recognized it, it became so obvious to me that it should be central in the book.”

Part of why Kent-Monning kept having gleams of realization during the writing process is because it was inextricably linked with the healing process. She had always been a writer, but never shared it with anybody. That changed when her husband left her.

“When I was going through that big life change, writing was something I just really leaned on,” Kent-Monning says. “I thought writing is something I could take more seriously, and now I have a lot more time and space: I don't have a marriage, I don't have all this stuff. So I started writing it.”

“Just be obsessed with your work.” - Giancarlo DiTrapano

At some point, she started following the writer (and Rose Books publisher) Chelsea Hodson on the website formerly known as Twitter, who at the time, was gearing up to lead a workshop in Italy with the legendary Giancarlo DiTrapano, the publisher of New York Tyrant, who passed away in 2021. She had to put together 20 pages for the application.

“I had all these fragments I had been writing. I would walk my dog and leave myself voice notes and write little things. I was like, well, let me put this together as an application,” she says. “That's really how it started, and I didn't have any intention of writing a book at first. I just wanted to go have an experience. I wanted to meet other writers. I wanted writing to be a little bit more of my life.”

When she got to the workshop, she felt encouraged by everyone to keep working — to dig deeper and to consider turning her writing into a long-form project. She went home with DiTrapano’s voice in her head, which she says has never left.

“When we were in Italy, Giancarlo was like: ‘Just be obsessed with your work.’ It helped because then I wrote my first draft in seven months, which I'll probably never do again, but I hear him in my head saying that all the time: ‘Just be obsessed with it.’”

The book retained the fragmented ways in which Kent-Monning first wrote, mimicking the feeling of what it’s like to pick up the pieces after someone has smashed the glass of your life, holding them to the light to try to see what is reflected and refracted. It’s this fragmentation that gives the book a meandering, primal feeling that’s reminiscent of the claustrophobia of the mind of Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond or the dark sentimentality of Scott McClanahan’s The Sarah Book, which was also published by New York Tyrant.

The structure also mimics the emotional whiplash of someone underwater: The prose is sometimes distant, other times voraciously close. Its short chapters and non-linear plot structure allow for digesting sections at your own pace, like letting the salt on fatty pieces of steak linger and melt on your tongue.

If it’s a seductive metaphor, it’s because it’s a seductive book: not just in bathroom bar sex scenes, but in desperation. Lexi is utterly addicted to men who aren’t into her, but that all-consuming desperation is what eventually resurrects her — it’s as crucial to healing as her listlessness.

“You have to go get your back broken. You've got to just go have crazy sex where it'll be healing. They'll probably get emotionally attached. You don't have to deal with all that, but what you need is a ray of light who feels different from anything else in your life,” Kent-Monning says. “You just need to disrupt your life.”