Life

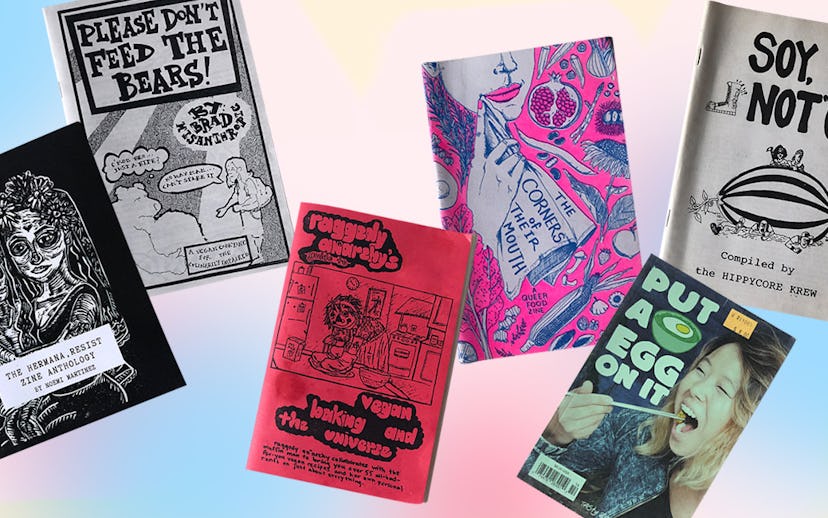

How Zines Became An Anarchist's Guide To Cooking Vegan

Times have changed, but zines are forever—and so is this epic brownie recipe

In our monthly column, Meatless Mondays, writer and host of the podcast, Meatless, Alicia Kennedy will explore veganism, social justice as it relates to food and home cooking—and, yes, there will always be a new recipe to try out for yourself.

Veganism has not always been marketable; hardcover cookbooks with a smiling photo of its author on the cover along with brightly colored, freshly harvested vegetables were not an easy sell. That's why, to learn vegan cooking, many turned to zines—DIY, photocopied, and bound by hand with staples or a simple fold. In those days before Veganomicon and Chloe's Kitchen, people like Shannon O'Neill, now an archivist at the Barnard College Library, would go into the East Village's feminist bookstore Bluestockings to ask if there were new vegan zines.

"Before there was a market for vegan cookbooks, zines were how I got recipes," says O'Neill. She tells me this in one of the upstairs rooms of the library, where she's accessed some of the library's zine archive for my perusal. Their collection prioritizes the work of women, cis and trans, and especially women of color. A search through its database for "vegan" brings up over 50 selections covering everything from eating disorders to class to genderqueer identity.

The overlap between veganism and zine culture is a natural one. Both exist outside the mainstream, creating a space ripe for recipes on one side of the page and erotic poetry printed on the other. Zines, being self-published and driven, don't have to be created to sell: A personal introduction by the author about wanting to liberate the world and herself, a story about watching a friend's home birth, and recipes for cookies and cakes all fit together, as in Raggedy Anarchy's Guide to Vegan Baking and the Universe.

Noemi Martinez, the longtime zine-maker behind Hermana Resist and a domestic zine with recipes called Homespun, has been vegan since 2005. "It started at a time when I was following the work of Cesar Chavez," she says. "Since then, I've come to believe that eating vegan is more in tune with my ancestral roots and something I have to follow for spiritual growth."

That diet also aligned with her interest in zines. "I call it 'edupunk,'" she says. "My beliefs of DIY ethos and way of life, including veganism, being queer and punk were very much influenced by zines."

The interconnectedness of various movements has always been on display in zines, unlike in mainstream coverage of veganism, where it's often presented as just a diet with no political or social justice connections. "In zines, veganism seemed to come hand in hand with other radical ideas and living vegan was secondary," says Martinez, "so I could see how living vegan worked with trying to live in our society—nothing was single issue."

André Gallant, a food writer based in Georgia, spent a short time as a hard-core vegan when introduced to it through Food Not Bombs, a network of independent collectives that gives out free meals. This work coincided with the 1990 release of Soy Not Oi! by the Hippycore Collective, considered the seminal vegan zine. "It was a textbook for much of what we did," he says.

Though he's no longer vegan, the ethos of those days influences how he continues to eat and live. "For me, the vegan food knowledge that I found in zines was part of a bigger DIY, off-the-grid, anti-capitalist ethos that pervaded the whole punk scene, but was particularly important in the South, which is where I've lived since my teens, still live today, and don't plan on leaving," he says. "Zines were snapshots of what we were eating and how we were thinking about what we were eating. Those documents connected towns just like seven-inch records did. Georgia zines went to Florida, North Carolina zines made it to Arkansas, Mississippi zines made it to Virginia. We couldn't text each other. We didn't have blogs. Zines are how we developed the ethic of being vegan and punk in the South."

Out in San Francisco, Sarah Keough, publisher of zine Put A Egg On It, learned of veganism while living in a punk house as a teenager where groceries were bought communally at Rainbow Grocery. "Food Not Bombs cooked out of our house once a week also and, because I was basically a runaway teen and I didn't have much money, I ate a lot of the extra stuff they left for us," she says. "My favorite thing was a bagel with vegan butter, a thin slice of raw tofu, a dash of soy sauce, and some nutritional yeast."

"There's a lot of overlap with vegans and zine culture," she says. "Anarchists, hard-core kids, sensitive queers, and animal rights activists mingled together at the same shows, same record stores, zine fairs, and bike swaps. Thinking about zines from as far back as the '80s, people were into finding their own ways to take care of themselves so you'd find personal zines talking about mental health and different kinds of self-care and also how to teach yourself to cook, cheaply and healthily. Vegan cook zines were some of the first places that taught me the basics of how to feed myself."

It can be easy to look at the zine moment as over—a relic of the '90s and '00s, as much a part of history as print magazines. But they continue to be a living form for the transference of information outside of an explicitly capitalist publishing system. In zines, veganism's pluralistic and political nature has long been on display. Whether one dips into a library's archives or pokes around online for copies of Please Don't Feed the Bears!, the influence of and knowledge shared in this DIY format keep the dream of a vegan movement engaged in the world beyond its hunger for ice cream and seitan alive.

Raggedy Anarchy's Fudgy Vegan Brownies

I've been making vegan baked goods for years now and often think I've seen every technique. But in Raggedy Anarchy, written by an anonymous 23-year-old "womyn," there was something I hadn't yet: a thick paste of flour and water, made in a saucepan over low heat, to bind the whole thing together—something eggs would usually take care of. As I made the recipe, which doesn't have big explanations for her thought process, I found myself in a sort of imaginary dialogue with her: How did you come up with this, and is it supposed to be this thick? Why did you add so much sugar—compensating for subpar cocoa? In my kitchen, a lineage of vegan baking came alive as I adapted her recipe to my pantry. Just some anarchists, hacking treats.

Ingredients

- 2 ½ cups flour, ½ cup divided out

- 1 ¼ cup water

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 2 cups sugar

- 1 cup cocoa powder

- 1 ½ teaspoons kosher salt

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 1 teaspoon almond extract

- ⅔ cup melted refined coconut oil

- Chopped nuts, chocolate chips, and flaky sea salt (optional, to taste)

- Preheat the oven to 350 and line a greased 8x8-inch pan with parchment paper.

- Over a double boiler or in the microwave, melt the coconut oil. Set aside.

- In a small mixing bowl, whisk together 2 cups of flour and the baking powder. Set aside.

- In a larger mixing bowl, whisk together the sugar, vanilla, cocoa powder, and coconut oil. Set aside.

- Over low heat in a small saucepan, whisk together ½ cup flour and the water, continuously, until a very thick white paste has formed. Add to the large mixing bowl and stir until well combined, in a grainy, chocolaty paste.

- Add the flour and baking powder combination to the chocolaty paste. Stir well. It will become a loose sort of bread dough, and you can use your hands if it gets hard to combine with a spoon or whisk.

- Fit the dough into the lined pan with your hands, making sure it hits every corner. Top with chopped nuts, chocolate chips, and flaky sea salt if using.

- Bake for 25 minutes or until a knife inserted into the middle comes out clean. Let cool completely before eating.