Entertainment

Why ‘Irrational Man’ Is the Last Woody Allen Movie That I’ll Ever See

rethinking the woody allen question

Woody Allen’s filmography is full of movies that were inspired by his own reality and reflect his personal philosophy. Recently, he's created more autobiographical works (think: Blue Jasmine, where a Mia Farrow-like Cate Blanchett tries to find her ground after going through a tough divorce, or Whatever Works, where an older Larry David finds joy in Evan Rachel Woods’s 41-years younger, lighthearted character, who could be a placeholder for Soon Yi Previn). But if you look into the earlier years, it’s more like Kantian clues sprinkled throughout the script (Crimes and Misdemeanors, the question of god’s all-seeing eyes), and the pointlessness of life, knowing the universe will one day soon come apart anyway (Annie Hall, Deconstructing Harry). According to the official production notes, the director’s latest, Irrational Man, marks the first time there is “a story that expresses an unvarnished picture of Woody Allen’s worldview,” which, official or not, any well-versed moviegoer would argue against.

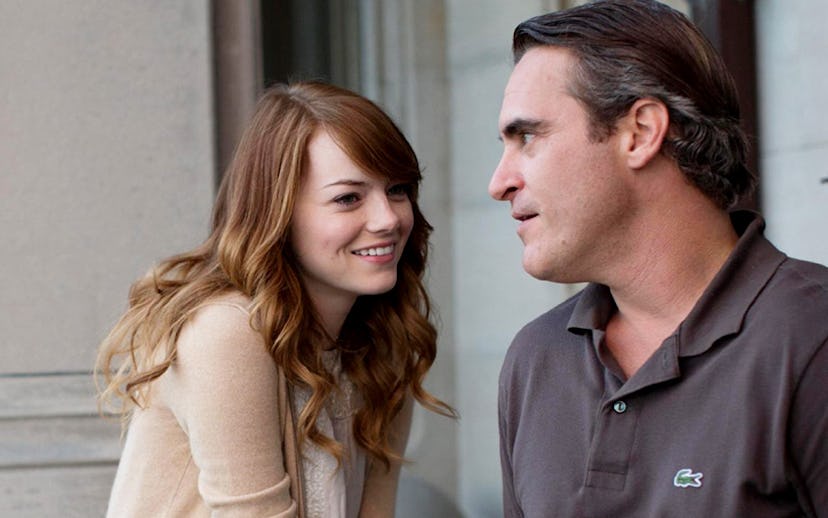

In a nutshell, Irrational Man follows Abe Lucas (Joaquin Phoenix), a jaded and dejected philosophy professor who is visiting faculty to a university on the east coast for the summer. Lucas has written his most acknowledged thesis on randomness and chance, has a drinking problem, and quickly finds himself to be the object of desire for two women: Rita Richards (Parker Posey), a married, preoccupied fellow professor, and Jill Pollard (Emma Stone), the bright and young student in Lucas’ summer session. The movie, as one would expect, is heavy-ish on philosophy—as in, one could make a Dead Poets Society-type super cut on Continental Philosophy 101. Drawing from thinkers like Kant, Kierkegaard, and Sartre, Lucas talks about good and evil, the anxiety of everyday existence, and the burden that comes with the imperative to make free choices every day. Phoenix’s character’s own life, devoid of meaning, changes completely through one of those free choices: The choice to kill a local, corrupt judge who, he finds out, intends to tear an innocent mother away from her children. From a philosophical standpoint, the planning and the act of killing makes perfect sense to Abe. By killing the judge, he rekindles his joie de vivre, and starts enjoying his everyday existence like other mortals do. “He is such an original thinker,” Rita puts it, in her ditzy way. “You can’t expect this brilliant mind to live and be judged by middle-class values.” Abe is content with himself after killing the judge, and even after his two love interests find out about the murder, they are more worked up about his obligatory departure from their lives than the actual crime he committed.

Most art appreciation takes some suspension of the self; a tucking away of the individual for however long you are engaging with a certain piece—especially if you are doing it for a living. However, I found it very difficult to watch Irrational Man without getting distracted, not because it’s a “bad” movie, but because its subject matter rings too close to home. The societal taboo in the film—murder—and how the murderer justifies that action to himself is eerily devoid of morality, not unlike how Woody Allen himself appears to have no remorse about the crimes he's been accused of. Much like Allen’s other work, the script of Irrational Man just has too many confessional, twitching hints for me to feel comfortable watching it.

Which brings me to two points that I think are equally important: (One) From now on, every time Woody Allen puts out a new movie, the audience should be thinking, “I’m watching a title from someone who has possibly committed these crimes,” which, in the aftermath of Dylan Farrow’s open letter, I felt very strongly. And (two), we should still be having a hard time trying to understand the desire to keep bringing attention to this director. Is it search for vindication? Because we can only hope that that vindication won’t be coming in a post-Polanski, post-Cosby world, even if Allen were to come up with his best work to date tomorrow. So did I enjoy the movie? At this point, it doesn't really matter.

Additional reporting by Jillian Taub.