We Traveled To The Literal Middle Of America And This Is What It Looks Like

our journey to smith county, kansas

In 1918, the United States Geological Survey determined that the dead center of America was a patch of farmland two miles northwest of Lebanon, Kansas. It was six years after New Mexico and Arizona joined the Union and long before Alaska and Hawaii ever made the cut. For centuries, this area has been host to bizarre characters, dangerous interlopers, prehistoric creatures, and even a few ghosts if legend serves. Maybe it’s that any small town in the U.S., if put under a microscope, would seem a little strange. As such, being from the middle is a distinction locals generally shrug off. But after everything that’s happened here, they’re just being modest.

About two miles outside of Lebanon (pronounced locally as “leb-nen”) stands a monument, completed in 1941. The marker consists of a broad, stone-based flagpole, a plaque, two flags (U.S. and Kansas), and a little white chapel—all commemorating Middle America, quite literally.

“I used to have a hunting dog, so I would drive up there all the time,” says Denise Marcum, the town’s librarian. “It’s nice,” she says, “people go up there to find peace.” Maybe it’s the chapel, or the dead-end road they paved to service the monument, or the loud winds that push the sunflowers surrounding the grounds into one another, but the site feels significant in a way that the world’s largest ball of twine—just 27 miles southwest in Cawker City—doesn’t.

Lebanon, population 206, sits a quarter-mile north of Route 36, in Smith County, which borders Nebraska. It’s a place where you can put the word the in front of everything. The grocery is Ladow’s. The hair salon is Betty’s Beauty Bar. The shop is Hoss’s Antiques & Gifts (run by Marcum’s dad). The gun shop is Higby Bros. (by appointment only). There’s the elevator—a large conveyor belt that deposits grain into a big silver silo—but nearly every town in the area has one. Sometimes it’s the only structure left standing. Agriculture is life out here, and in Lebanon, other businesses are few and close together. There were once two hotels in town: One became Hoss’s and the other looks to be abandoned, paint stripped, and in bad shape.

“Last month a white supremacist came knocking on doors, asking about property,” recalls one resident, who asked to remain anonymous given the sensitivity of this ongoing threat. “The mayor came by and asked if anyone had seen him.” The folks in town believe the man was in the area trying to start up an Aryan utopia—a feat white nationalists attempted in Leith, North Dakota (they ultimately failed). There’s plenty of empty lots in Lebanon, but there’s no room for men like him. The townspeople guided the stranger to Route 36 and told him to get out. “I miss all the good stuff,” the resident says. “You never wanna miss a good kicking out,” replies a friend.

Smith County has one of the oldest populations in all of Kansas. You can count the number of kids who can drive in Lebanon on one hand. There used to be a primary school, but now the inside has been converted into a local man’s workshop, and the entrance is guarded by a pack of New Hampshire Red chickens. The foxes can’t get at the Hampshire Reds in the front of the single-story building because the streetlights scare them off. Just next door, also appropriately on School Avenue, there sits a boxy, brick, two-story high school building, which is now a genealogy center and storage for antiques. According to one resident, “nobody pays much attention to it.” Nowadays, the few school-aged kids in town get bussed 14 miles to the west, to Smith Center, the largest city in the county with a population of around 1,600.

There are few if any structures lining the 15-minute drive between Lebanon and Smith Center, just a single-lane road and hay and rows of corn. It’s a visually simple and beautiful part of the country, if a little eerie, especially this time of year when the fields are green-brown and it’s light-jacket-cool in the mornings. Smith Center is the sister town to Lebanon, and together they are part of this often overlooked but deeply fascinating region of the country.

ONE TOWN OVER

Anything that would be considered youth culture happens in Smith Center, and it’s divided by gender. The girls in town lucky enough to get and keep the gig work for Merry VanderGiesen at Jiffy Burger on Route 36, and the boys who practice hard enough play for the fabled high school football team, the Redmen. VanderGiesen has owned and operated Jiffy Burger for 33-and-a-half years. She guesses in that time she’s employed 400 to 500 girls. Inside the diner, walls are peppered with photographs of James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, and the booths are ’50s-style two-tone vinyl. There’s even a Ms. Pac-Man machine in the corner that fits perfectly within the restaurant’s strict color palette, pink and white.

VanderGiesen’s employees are always female, mostly high school age, and all wear pink T-shirts at work. “The girls come and they apply and I start ’em,” she says. More than any other place in the county, Jiffy Burger is alive with the sound of gossip and laughter. One of the girls has just had her wisdom teeth pulled, and she’s carrying a picture of the aftermath. “Merry, do you want to see my teeth?” she asks. “No, I don’t. That’s gross,” replies VanderGiesen, both of them laughing now. “Go home, honey, you’re tired.”

Everybody gets a kick out of Merry, especially her girls, but more than a comedian or a boss or a cook, she is a source of guidance for young people in town. “You know, I truly get some girls here that, I mean, they’re not neglected at home, but in today’s society, most parents have to work,” she continues. “These girls have no one there when they get home from school to tell how their day was, blah, blah, blah. So where do they come? Here.”

If you want to know about Smith Center, the book Our Boys is a good starting point. Written by Joe Drape, in 2010, it outlines the small-town heroics of the high school team, who this year are already 3-0. On Friday, September 18, the Redmen traveled 90 miles south to Hays, the largest city in north Kansas with a population of around 21,000, to take on Thomas More Prep-Marian, a Catholic high school. It was TMP’s homecoming, and the game drew such a large crowd that the event was moved to Fort Hays State University’s field. The Redmen won 40-0, but at halftime TMP crowned its homecoming king and queen under the bright lights of the stadium. Parents and fellow students snapped pictures during what was a perfect Midwestern ceremony.

For visitors, this type of storybook Americana, with its pristine landscape and heartfelt displays of small-town camaraderie, is magnetic. The region is quintessential Great Plains farmland—“God’s country,” if you will. The mostly Christian folks are spread thin over flat expanses of beautiful earth. Teenagers peel out of parking lots in pickup trucks, then drive around for hours, listening to music and smoking cigarettes. Somehow, in the face of this seemingly immovable Middle American standard, Smith County left the door open for the unexpected, and in walked the utterly weird.

HERE COMES TROUBLE

On a Saturday morning, a woman selling coffee talks about the football team for a few minutes before she mentions the TMers. “It stands for Transformative something…it’s all about souls floating over bodies,” she says, standing in her shop on Route 281, which cuts through the middle of Smith Center. “They came a few years ago, bought up a bunch of land,” she continues. The letters TM in fact stand for Transcendental Meditation, and in March 2006, representatives of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the creator of the practice, broke ground on a 380-acre settlement in the north of Smith County, which would be called the World Capital of Peace. “I think it’s because of the geographic center. They can send it out in all directions,” jokes a man in the coffee shop, who is mimicking the hands-on-temples, closed-eyes gesture of a 10-dollar psychic.

The initial TM project was composed of a 12-to-15-building campus at an estimated cost of $14 million. The Maharishi died roughly a year after the groundbreaking at 90 years old, but ultimately the project was stalled because of Smith Center and Lebanon’s crusade against what the more religious members of the community deemed a cult.

Transcendental Meditation is, according to its own literature, “not a religion, philosophy, or lifestyle.” It is a technique that requires practitioners to repeat a personalized mantra with eyes closed twice a day for 15 to 20 minutes. In the 1960s and ’70s, the Maharishi famously provided guidance to the Beatles and members of the Beach Boys. In 2005, filmmaker David Lynch created his eponymous foundation, which uses the Maharishi’s TM techniques as the backbone of its organization. Celebrities like Jerry Seinfeld, Ellen DeGeneres, Russell Brand, and Lena Dunham have all spoken to the merits of TM.

The World Capital of Peace was never completed, though nearly a dozen structures still stand on the property, all in various stages of completion, and all with entrances that face east to greet the morning sun. It’s unclear what would have been the goal or function of their Smith County location. Suffice it to say, enough of the local community didn’t want to find out. The rumor around town is that somebody reported finding a satanic doll on the proposed grounds, which enraged the local churches, who ultimately dug in the hardest against the TMers.

Today, nearly a decade later, the complex has a single resident, its lone caretaker, Gary Weisenberger. A practicioner of TM himself, Weisenberger does work on the property including some organic farming. He also watches over the grounds to ensure, among other things, that local kids don’t throw beer bottles on the premises. Weisenberger stays in the one nearly finished building on the campus, a stark white, plantation-style mansion with wraparound porches on each of its two floors. The colony is now a remnant of a saga that everyone in town knows about, but is also a place few people have seen up close. Bob Levin, a.k.a. the Boneman, is one of the few other locals who know precisely where the decrepit settlement stands. But like many of Smith Center’s residents, Levin doesn’t really care much about the TMers anymore; it’s just noise that takes him away from his real interests.

THE BONEMAN

Levin’s résumé is extensive, but at the moment he’s a weather reporter, a ham-radio broadcaster, a jokester, and a self-taught paleontologist, hence the nickname, which appears on his license plate. He’s been into bones for more than 65 years, and he does a lot of hunting for marine fossils on his motorcycle, scanning the farmland north of Smith Center and Lebanon.

“Everybody in town thinks I’m a weirdo,” says Levin, who along with his wife, Linda, is one of Smith Center’s most public and joyous residents. Bob, who’s 78, is drinking coffee and flirting with the waitress inside Paul’s Café & Dining Room on Route 36—“the office,” he jokes—while Linda polishes off a pancake and salutes to her older husband’s great health. “He still goes three times a week,” she says of his fossil hunts. “He’s in great shape. All he needs is a blood pressure pill and his vitamins.”

Just last year, Bob discovered the remains of an 88-million-year-old mosasaur called a Tylosaurus proriger, a 28-to-30-foot marine reptile from the Cretaceous period. “My Tylosaurus lived in the sea that covered the Smith Center area,” he says. “This all used to be water.” Some of the first visitors to the region, as it turns out, were large, aquatic creatures swimming in what was, 100 million years ago, the Western Interior Seaway. For Bob, fossils are not a hobby but a life’s work.

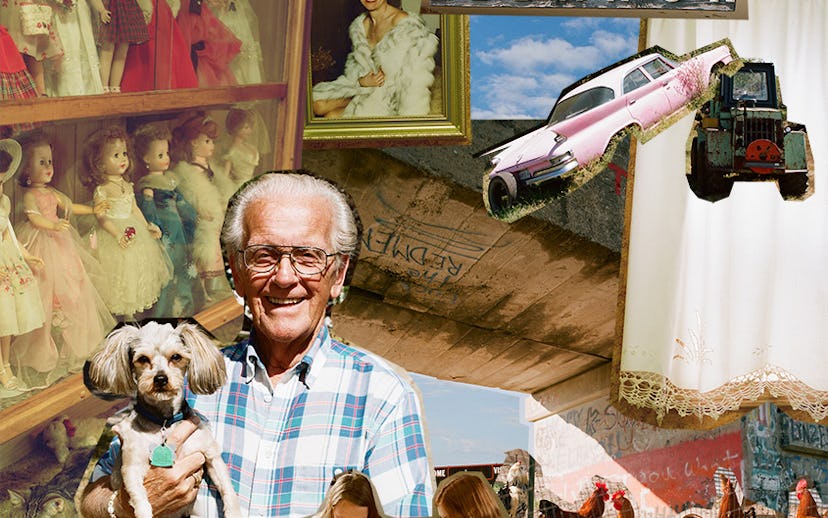

Inside their house, the walls tell the story of two devoted collectors. Not to be outdone, the top floor is Linda’s, with nearly every visible surface holding or in service of her incredible doll collection. “A woman came all the way from Hastings [Nebraska] to write about this one, she was so mad that I wouldn’t take it out of the case,” says Linda, pointing to her prized doll, permanently sealed in glass.

Bob’s bones are housed in the basement and out in what was once a stand-alone garage and is now a two-room museum filled with hundreds of fossils, some framed magazine clippings, and even a campy, pinup-style photograph of a young Linda wearing only a fur coat. Bob says it’s a shot he saved from his days as the area’s wedding photographer. Downstairs, amid countless cases of meticulously labeled bones pinned to fiberboard walls is Bob’s guestbook. In it are the names and addresses of visiting academics, travelers, journalists, and even a man from Kenya he met in Paul’s Café one day.

When Bob passes away—something that comes up often and is discussed lightheartedly—his entire collection will go to the museum at the Rolling Hills Zoo in Salina, Kansas. He wants to keep the fossils together and close by, but more than anything Bob likes Rolling Hills because kids from all over the region take field trips there and will be able to learn from his discoveries. Back at home, above Bob’s desk, there is a message pinned up in Latin. It translates to: “This place is where the dead teach the living.”

GHOSTS ON TAP

Across town at the Lyon Saloon, Roe Jene Timmons is experiencing the same: “We have six ghosts, but they’re all friendly,” she says. Timmons, who is VanderGiesen’s cousin, owns and operates the newly renovated saloon in Smith Center. She strikes an intimidating figure—tall, with long white hair, crystal blue eyes, a coarse voice, and wearing a 50th-anniversary Harley-Davidson top—but Timmons proves to be, more than anything, welcoming, kind, and curious. She inherited the saloon from her late, close family friend, for whom there is a large photographic memorial in the dining section of the bar. According to Kansas law, the Lyon has to sell 30 dollars of food for every 100 dollars of booze, so she works double-duty, slinging drinks and cooking a mean chicken-fried steak.

“He wanted the naked ladies on the floor, so…,” says Timmons, gesturing toward a painting—adhered to the ground—of a reclining nude woman, done in the impressionist style. “Do you want to see the chandelier?” she asks. Back behind a closed door is a small area with a staircase lined with reproduction paintings of Picasso and Rembrandt. The stairs lead up to the apartments Timmons occasionally rents out to hunters and travelers. “We were in here one time and it just kept moving around like this,” she says, now swinging the chandelier in a circle. “We’d stop it, and it would just start going like this,” she continues, moving it again, slightly, in a tight spiral. According to Timmons, the saloon has welcomed two paranormal teams, all of whom visited eagerly and confirmed the presence of the great beyond.

Between a white supremacist, a colony of meditators, dinosaurs, the supernatural, and general life, this little part of the world has had a lot thrown at it. Through it all, the townspeople are warm, resilient, blasé when it’s appropriate, and morally principled. Whatever the situation may be, things are dealt with internally—no tattletales in this part of America. If you want the story, you have to go there. Vander-Giesen puts it best when talking about her girls: “We get it all. And we handle it.”