Entertainment

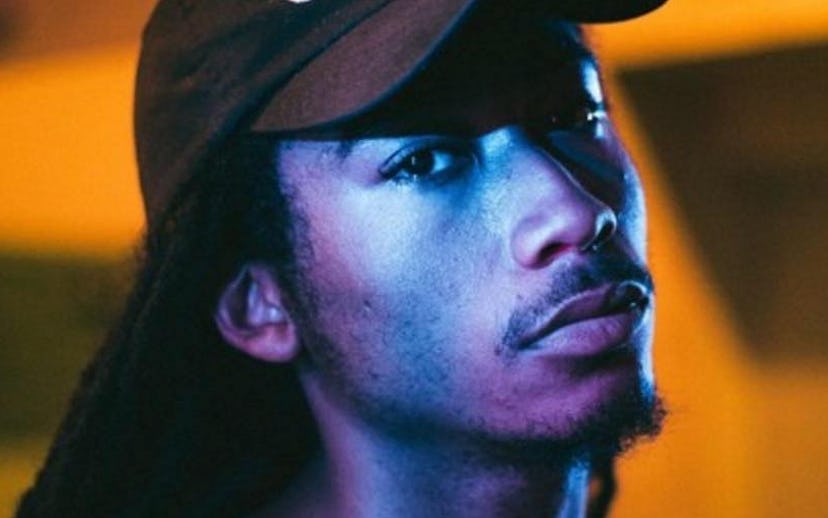

By Embracing The Past, Topaz Jones Might Just Be The Future Of Rap

Time to play

Arcade, the new album by Topaz Jones, is perhaps the ideal rap record for 2016. It’s lush, bouncy, and melodic, drawing on the same funk and soul influences that we’ve seen artists like Anderson .Paak and Childish Gambino mine recently. Jones, like the aforementioned acts, is a versatile vocalist who sings nearly as well as he raps (which is to say quite well). It’s the kind of flawlessly of-the-moment record that a cynical or uninitiated listener could interpret as opportunistic.

That is, until you talk to Jones for even a moment about the path and the journey of self-discovery that led to Arcade, in which case it becomes abundantly clear that he would’ve made this record in 2016 or 2006 or 1996 and that he's the furthest possible thing from a trend rider, even if his timing was impeccable.

“Something clicked with me after I put the last album out [2014’s The Honeymoon Suite]. It probably had to do with graduating school as well, and being on my own, and having that thought like, You’re in the face of being broke right now. You could either chase your dreams and it could go great or you could be broke for life. So how do you want to do that from an integrity standpoint?" Jones says.

That dilemma caused Jones to turn his probing inward; where old songs like “Coping Mechanism” were about social issues in a way that was hard-lined and literal, Arcade is more internal and allegorical, part introduction to Jones as an artist and a human being defining himself amid a barrage of lights, sounds, and screens.

“At the time of making the album, I was so lost as an individual and looking for that identity and that purpose and that thing that distinguishes me from the next person that the entire album ended up being about that process and I think that in itself is a social issue,” Jones says. “The idea that we’re more lost than we’ve ever been, because there are so many options for curating an identity that isn’t your own.”

There’s another component to the record, too, and it’s what inspired the vintage title: a Black Mirror-esque look at society’s social fragmentation, inspired, fittingly, by a kind of entertainment mecca that had its peak during the heyday of Jones’ musical influences.

“I was channeling a lot of ‘80s funk in the music and finding my own sound, and, for me, that was reminiscent of the arcade era. I started to think a lot more about that form of entertainment that was so big then,” says Jones. “Just one generation before mine, if you wanted to connect with people and find entertainment, you had to go out and seek it and be around other people and experience it in a different place versus just having it in the palm of your hand the way you do now.”

Jones, now 23, graduated from NYU’s Clive Davis of Recorded Music, but the majority of his musical inspiration comes from much earlier. A childhood spent around his father, Curtis Jones, a musician who played with funk bands throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s and raised him on a diet of acts like the Ohio Players. Those experiences gave him a deep appreciation for musicality and his mother’s background as an activist and academic gave him a thoughtful, probing quality. Perhaps most surprisingly is that his upbringing in Montclair, New Jersey, gave him the opportunity to cut his teeth as an MC, and he describes the experience as the impetus for his development on the mic.

“There was this culture around the high school where everyone was very ‘90s rap influenced from the way they dressed to the way they talked, some of the slang. It kind of felt like it fell out of the movie Kids, like Harmony Korine and shit,” Jones says of his East Coast upbringing. “I think being in that environment, when I decided I was going to really tell people that I was going to take rap seriously, there was a lot that came with that and part of it was proving myself to the other rappers and people who cared about music.”

Those back-of-the-party high school ciphers clearly paid off; he displays a nimble, cocky flow on “Tropicana,” and on “Winona” he shines with intricate wordplay that folds into itself like the cities in Inception or Doctor Strange.

But while it’s easy to picture Jones’ upbringing being something like a mid-2000s version of The Get Down, his broader musical talents help elevate the record at its most intimate moments. On the latter section of the double track “Get Lost/Untitled,” Jones is at his most vulnerable, singing atop nothing more than some sustained piano chords. It’s a haunting song, one that makes you reflect on any difficult crossroads you’ve ever faced, the kind of intimate post-Blonde ballad that fleets between the universal and the hyper-personal.

It would be easy to assume that Jones is the kind of free-spirited, genre-jumping artist who would be a proponent of abolishing genres, especially because he’s the kind of artist who doesn’t fit neatly into any two-syllable definition. However, his response is more nuanced and thoughtful, based on a desire to be able to create without being compared to his musical ancestors despite them having little to do with each other stylistically.

In fact, Jones may have created the signature phrase for these issues over whether an artist pays sufficient homage. He referred to it as “Yachty Tension,” connected to the Atlanta rapper whose unorthodox style and self-professed lack of knowledge of those who came before him has caused huge stirs on rap blogs.

“We need to hurry up and give things subgenre names; I think everybody would be a lot happier if not everything had to fit under this blanket umbrella of hip-hop. It could still all be hip-hop, but it’d be like how rock music isn’t just rock music, there’s punk, there’s psychedelic rock, there’s every type. Because they have those spaces to live in, you don’t have to be a punk band and pay respect to Chuck Berry,” says Jones.

Even still, it’ll be a long while before anyone comes up with a subgenre name fitting for Jones’ retro-inspired, yet impressively afrofuturistic, style that effortlessly blends not only funk and soul but also new and old-school rap simultaneously. And even when the appropriate term is created, it’s safe to bet that Jones will be on to something even bigger, better, and harder to box in.

Topaz Jones has his first headlining show at the Knitting Factory on December 13.