Turning Pointe: How Hip-Hop Ballet Is Redefining Dance And Discipline

“We can do it because the space between our ears tells us that we can”

The following feature appears in the September 2017 issue of NYLON.

Homer Hans Bryant exudes an aura of brightness and joy. So it feels somewhat incongruous that the Chicago Multi-Cultural Dance Center, where he spends most of his time, is in the basement of an old train station with no cell service, buried deep in the bowels of a big, red Romanesque Revival-style building on Dearborn and Polk.

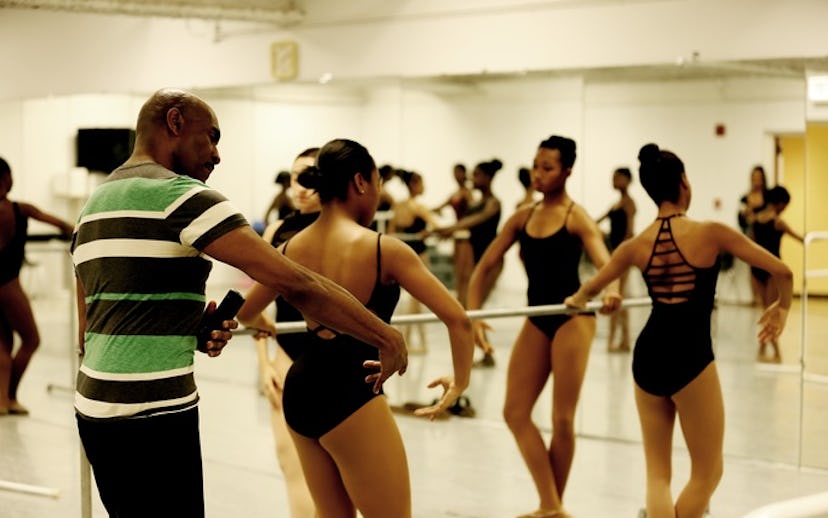

In many ways, the basement is an equally unsuitable place for some of The Chi’s youngest and most talented cultural ambassadors. The dancers who train under Bryant have recently become viral social-media sensations thanks to videos of them performing Hiplet (pronounced hip-lay). Bryant has spent years developing this version of ballet that combines classical technique with African, Latin, and hip-hop dance—movements rooted in various communities of color.

From certain vantage points, it seems like his work is finally paying off: over 700 million video views, appearances on all the big daytime TV shows, performances around the globe. But, according to Bryant, “The thing, now, is to get out the basement.”

I’ve known Bryant (or “Mr. Homer” as his students know him—teachers and elders at CMDC are called by familiar, familial terms) for all of five minutes, and he’s already given me a personalized gift: dangly, kente-patterned earrings he’s hand-sculpted out of fabric cut out to look like pointe shoes, covered with some sort of epoxy. He crafts ballet-themed accessories—pins and bow ties in addition to earrings—in his spare time because he likes to work with his hands. “My grandfather was a carpenter,” he explains, showing me the foot stretchers he also fashions. “I mold kids through the discipline of dance, but I feel like I’m a carpenter.”

Bryant’s school is home to 285 students, now “mostly kids of color,” he says. Considering over half of Chicago’s population is black or brown, this makes sense. But CMDC is primarily a classical ballet school, and Chicago’s demographics don’t change the fact that many traditional dance spaces are often predominantly white—something Bryant saw time and again during his early days of guest teaching out in the suburbs, and something he wanted to actively work against. So when he opened the doors to his school in 1990, he knew he had a challenge ahead of him.

“I was like, ‘OK, how am I going to connect with my people?’” he says. His “aha” moment came one night while he was at a rap show in British Columbia, Canada: “The kids in the audience [were] singing every word, and I walked away with that—’I wanna put rap and ballet together.’”

Next thing I know, Bryant breaks into his own rap: “I’ve got a story to tell, one of the best/ This is a story, above the rest/ It’s about a discipline that starts people clapping/ The only discipline you’ll ever hear me rapping/ My name is Homer, I’m here to say/ I am the guru of the rap ballet.”

I start to ask him if, back then, he was just using rap as a way to teach about—He jumps in. “No. When we went out there to perform, I was using rap to bring black kids, multicultural students into my school,” he says with a laugh, his levity not belying the importance of his message. “The school is 28 years old, and used to be called Bryant Ballet. In the ’90s I changed it to Chicago Multi-Cultural Dance Center to reflect the diversity that was coming in.” Rap ballet was working.

Back then, there was no dedicated class for the hybrid technique—students learned it when they were taught specific choreography. Bryant would adjust the rap ballet’s cadence and movement vocabulary to reflect the times—“the running man, the moonwalk, whatever the dances, we were doing them”—but at the core it was always classical ballet infused with soul.

Now under the moniker Hiplet, it’s taught as a one-hour class every Friday, as a way to work some different skills after a full and rigorous week of highly technical, classical training. “I usually put in a lot of hours of work. Every day I’m here, I’m trying to get better,” says 14-year-old Jacksyn-Symone Sallay, who’s been dancing with Bryant for seven years. She tells me she trains in ballet “five to six days a week.” I ask her why she chooses practicing dance over, say, a teenage social life. “Because I realize how much time and effort dance takes to succeed,” she says. “Dance is not easy.”

This is why the girls in the viral videos train for 12, 13, 14 hours a week. Hiplet’s not even an option for students before completing all of the traditional prereqs: picking up pencils with their toes, working with Therabands, stretching their feet in Strengthening for Pointe, training on half-toe in Free Pointe. They finally get their first pointe shoes in Basic Pointe, where they spend at least two years before moving on to Intermediate Pointe. Only then, with Bryant’s permission, can they take Hiplet. According to Bryant, it’s about building strength, and getting the students to believe in themselves and their ability.

He’s aware of what some skeptics have said: Hiplet isn’t good for the ankles. His students’ feet are bad. They shouldn’t be doing that. “Some of [my students] don’t have the best feet. Some of them have got beautiful feet. But you gotta remember, we’re descendants of slaves. We worked from Monday to Saturday. Sunday we had church. And dance,” he says. “Some of our ankles are retracted from our ancestors. When we do what we do at Hiplet and ballet, trust me, they are rejoicing with us. That’s what I tell people all the time. Our ancestors can feel the thunder under our feet.”

For Bryant, that lineage is key: “That’s why we’re so strong on pointe. That’s why we’re so good at what we do.”

Two decades and over 100,000 Instagram followers later, it seems like Bryant’s no longer worried about how to connect with his people. “Mr. Homer is kind of like a mentor that all shades of brown girls in Chicago look up to,” says student Imani Arnett. She started dancing later than most, at 12, but advanced rapidly in CMDC’s nurturing environment. “If you’re an African- American or person of color looking to dance, you will always get recommended to his studio.”

And thanks, in part, to Hiplet, Bryant’s reputation extends beyond city—and dance-world—limits. “Hiplet has become a global phenomenon because it is for all the people who like the technique of ballet but don’t necessarily like classical,” Cheryl Taylor tells me as we sift through sequin-and-spandex-stuffed garment bags, looking for hats to complete outfits for the next day’s performance. I’ve followed the school’s Auntie-like administrator into the costume closet to get her take on Hiplet’s popularity, but this is an all-hands-on-deck operation. Dance can be a very cost-prohibitive activity; to help make it possible for their students, Taylor tells me, they recycle costumes and, when they can, even provide shoes. “We have touched a nerve with folks; we get so many emails, social-media posts, Facebook messages from people around the world who say, ‘I would have stayed in ballet class if it were like this,’” he says.

The thing about enjoying a meteoric rise based largely on the internet, though, is that there’s a lot the world doesn’t get to see.

I’ve only been at CMDC for a day, but it’s already clear to me that the magic of a Bryant education is about so much more than gettin’ down while on ya toes.

“It’s important for black dancers to have a place where they can feel at home, where they can see themselves, where they can be trained by people who’ve experienced what they have or will experience,” Taylor tells me. “And we don’t have all black teachers, we mix it up, but they come here and they’ve got Mr. Homer, they’ve got me, they have other teachers who have traveled the path.” Taylor knows what it’s like because, as she says, she was born in a ballet body with a soul that wanted to groove. She knows the struggle because she lived it, as a working dancer, for years. “When you’re black, your path is different, because sometimes you will be the only one in the room. Sometimes you will be the only one at the audition,” she says. “And you know you have to push harder, fight harder, dance harder, dance better, sometimes, just to get recognized, and so here, we train [students] to do everything, so that they can be greater.”

Dancers in the school’s youth professional training program have to do at least one year each of African, Latin, jazz, and tap. They do two to three years of contemporary and modern. This is all in addition to a minimum of three ballet classes per week (five for advanced students). “You gotta do every style here, so that when you go out in the world, no matter what is thrown at you, you got it,” explains Taylor.

Confidence in his students—as rigorously trained dancers, as humans in the world—is why Bryant hashtags nearly everything he posts #becausewecan. “So many people have been saying we’re black and we can’t do this and we can’t do that, so I always put ‘because we can.’ It’s about pushing positivity,” he says. “We can do it because the space between our ears tells us that we can.”

Despite Bryant’s uplifting messaging, Hiplet still has haters. “Not only do I get people dissing me, I get people wondering why I’m not using dancers that are not of color. It’s crazy,” he tells me later over the phone. “I get, like, ‘Why can’t white girls be in your Hiplet thing?’ But if you come to my school, then you’ll be in my Hiplet thing!” Anyone can train at CMDC; there are no rules about who’s allowed through the doors. Just ask Lady Gaga, who’s taken private lessons down in that basement. Other notable students? “Sasha and Malia Obama would have been Hiplet ballerinas if their path was different—if they didn’t have to go to the White House,” Bryant says, noting that the former first daughters trained at CMDC for years.

“I think the thing with me, or many other black dancers, when Hiplet first came up, was that it was a bit frustrating that [Hiplet] was what was getting recognized so much,” says Zoe Buess-Watson, a classically trained dancer living and working in New York, pointing out that some of the pushback is an issue of space, figuratively speaking. When you live in a society where people of color are considered a monolith, it often feels like there’s no room for us to be all that we are: “You know, like in a movie, there’ll be one black friend? That’s kind of the same everywhere. So it felt like they’re taking all the attention away. [Like] people won’t be able to recognize all of the other great black dancers,” she says.

And it’s true—we been on point(e), but rarely get recognized. You’d think Misty Copeland was the first, the only, black ballerina. How many people outside of the dance world have ever heard of Michaela DePrince or Ingrid Silva or Lauren Anderson?

“When I found out more about what Homer was doing, it made me think about it in a completely different light,” Buess-Watson continues. “Personally, I’m not a big fan of the choreography, but I love that he’s creating this space for black dancers to feel completely comfortable, because I never felt that. I was definitely not the stereotypical ballerina when I was in training. I always had to adjust myself to that [classical ballet] world.”

“You know,” she reminds me, “when Martha Graham first invented her modern technique it was a huge scandal because she was ‘changing’ classical ballet, and now, it is a very widely taught dance form.” Katherine Dunham, the queen mother of Black Dance, has a similar story. What Bryant’s giving ballet is much like what Dunham gave modern: a coherent lexicon of African diaspora movement.

Not all detractors have changed their tune, but Bryant’s unfazed. He’s out here defiantly clappin’ back with more than just hashtags: “‘Don’t Sweat the Technique,’” the title of CMDC’s June showcase, “is because we got technique!” he tells me with a laugh one morning. The man is never off brand. The way Bryant sees it, there’s a huge difference between adding challenges and lowering standards. “I showed this Hiplet stuff to [Dance Theatre of Harlem co-founder Arthur] Mitchell when he took me to Russia in 2012. He said, ‘You’re on to something. Just make sure their classical ballet is strong.’”

“Hiplet is just one thing within several other things,” says Carl Jeffries, who’s been teaching at CMDC for seven years. Jeffries has danced all over: He began breakdancing on the Southside, and went on to be the only black man ever to dance with Mordine and Company (the Midwest’s longest-running contemporary dance troupe). “If ballet is classical—and it is—it’s not specifically classical for one particular race. It stands on its own as ballet,” he says. “[What we do at CMDC is] still classical ballet. But no one told us we couldn’t do other things with it.”

I ask him to describe some of the features of “classical” ballet: “Nutcracker, Swan Lake, all of the traditional stuff,” Jeffries tells me. “OK, that’s good, it holds its own, but do you stop there? If you take a second position on pointe, and go deeper, is it not second position on pointe? If you take a parallel position on pointe and get in your plié, and then open and close your legs, is that not allowed?” We’re sitting in the foyer of Benito Juarez Community Academy. People are pouring in to pack the auditorium for CMDC’s recital, but Mr. Carl’s asking no one in particular. “It’s allowed. Now that Mr. Homer is approaching [ballet] like that, everyone’s freaking out, like he’s gonna take something away from it.”

Jeffries doesn’t see it that way, though. “He’s adding to it. He’s layering it. He’s building upon the foundation of what is classical ballet in a hip-hop sense. In an African sense.” More Afrocentric, less Eurocentric. An approach that simply addresses black and brown bodies. Hiplet rejects the submission of our bodies to standards that deny them.

This approach encompasses all aspects of training at CMDC. For example, in traditional ballet schools, female students are typically required to wear pink tights and slippers, because the OG ballet dress code was made with white bodies in mind. “In our school we have brown tights. Why? Because brown tights go with brown bodies,” Jeffries explains. “That’s getting [students] to have a good self-esteem about themselves, feel confident about who they are.” (Dancers of color were finally able to buy flesh-toned pointe shoes for the first time after dancewear shop Gaynor Minden released brown shoes in two hues at the beginning of this year. But students at CMDC have been dying, painting, and pouring concealer on traditional pink shoes to make them brown for years.)

“You put them with something that they can relate to, feel comfortable in, and then you address them in that way,” Jeffries continues. “[You] teach them the same fundamental principles of classical ballet, without demeaning or disrespecting them, or making them feel some type of way, so they’re able to approach the discipline and keep the integrity of the historical preference, but with a confidence and recognition that ‘I could do this, too.’ Now the self-esteem is off the roof, because they see other black bodies like them, other advanced girls that are more flexible and everything, and they go off to the top schools.”

Students like Imani Arnett prove Jeffries’s point: “The studio is almost like a safe place to explore yourself and have fun with your friends, to move on with your technique and grow and get stronger,” she says. She’s headed to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts in the fall. “It’s just a whole family as soon as you walk into the doors of CMDC, like you’re absorbed into this freeing life.” How does she define Hiplet? “Free movement and expression to be yourself, whenever.”

“Passing it on,” according to Jeffries, is another core aspect of CMDC’s mission. This goes hand in hand with the notion that you can’t be what you can’t see, which drives much of Bryant’s work.

Bryant began dancing thanks to the generosity of a friend’s mom who paid for his first six months of lessons in St. Thomas, where he’s from. Not long after starting his first dance classes, his teacher noticed his natural talent and suggested he study classical ballet. “I didn’t realize what that meant, until Dance Theatre of Harlem walked across the floor, years later.” It took seeing other dancers that looked like him, dancing beautifully—proving that it was worth it—for him to realize his first dance teacher was right. “That next day, I asked to take a class,” he says. Soon after, DTH co-founder Arthur Mitchell made him an apprentice, and eventually invited him to tour with the company.

“I have not looked back since that day,” Bryant says. “For me, Mr. Mitchell was the ultimate mentor.”

In many ways, Bryant is following in Mitchell’s footsteps. Mitchell also had his dancers wear flesh-toned shoes and tights. He also used dance to push back against the cultural residue of anti-blackness that touches all aspects of American life. “Don’t forget—Mr. Mitchell started Dance Theatre of Harlem after the death of Dr. King,” Bryant tells me when I ask how Mitchell’s tutelage led him to open CMDC. “He was in Brazil doing something, and he said, ‘Why am I here doing this? I should be doing stuff in Harlem with my own people.’”

“I always hear my grandmother and grandfather in my ear. And my mother. And Arthur Mitchell. What would Mr. Mitchell do? You know, the people who are my elders,” he says. “That made it possible for me to be doing what I’m doing—I just hear their voices in me all the time.” Reaching back inspires looking forward.

It’s just after 5am for Bryant, but his greeting of “Early morning, early morning!” floats buoyantly through the phone on the same undercurrent of laughter as always. He’s up for an early call time with a group of Hiplet dancers on a work trip in Los Angeles, a “secret project,” likely the result of walking through one of the many doors that have opened since Hiplet went viral. “These kids have been to Seoul, Korea, they’ve been to Spain, they’ve been to Germany, they’ve been to the Virgin Islands—this is our fifth time out here in California. Ya know, it’s crazy!” he tells me, proudly, careful not to take all the credit. “They put in the work.”

And there’s that legacy again: Just like Bryant, they’re doin’ it for the culture. In many ways, this is much bigger than ballet.