Entertainment

The American Health Care System Gaslights Claire Foy In ‘Unsane’

Bet Queen Liz misses Britain’s ways now

Last week, Steven Soderbergh tweeted out “Picture wrap on HIGH FLYING BIRD at 1:09pm. First cut complete at 3:41pm.” His new film, announced in February, had been shot over two weeks. Frequently shooting on an iPhone, serving as his own cinematographer (as “Peter Andrews”) and editor (as “Mary Ann Bernard”), and editing as he shoots, Soderbergh works with a brute technocratic efficiency that parallels his narratives. In Soderbergh’s plots, characters are moved along, station-to-station, by genre machinery as inexorable as the grinding gears of capitalism. The protagonist of Contagion is an actual virus, which spreads across a far-flung supporting cast with a pure logic found most often within libertarian-leaning economics textbooks.

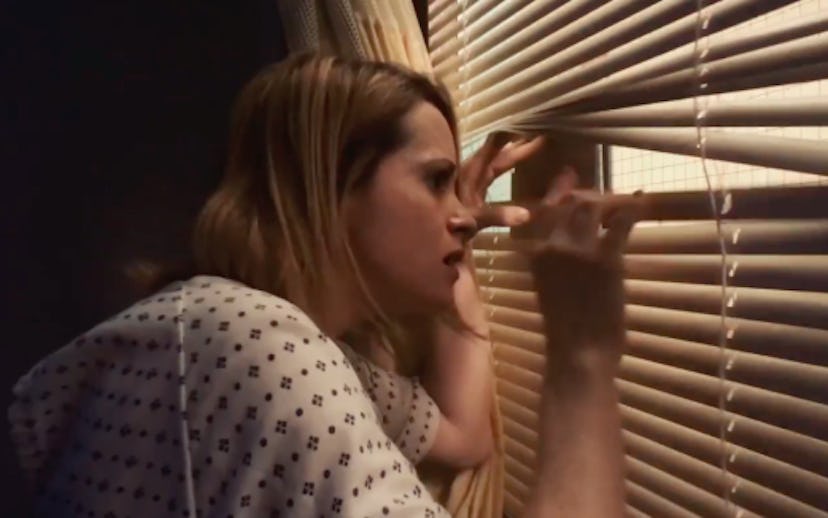

For her starring role in Soderbergh’s Unsane, Claire Foy joins the rat race. Queen Elizabeth’s flattened “American” accent serves her well as Sawyer Valentini, hard-charging career woman in a dog-eat-dog world. (Sawyer works in a bank, and is first seen dressing down an unqualified loan applicant over the phone—a woman, she tells a co-worker.) She takes charge of a Tinder hookup but breaks down when she’s overtaken by a sudden traumatic memory of powerlessness. Soon, she’s Googling support options for victims of stalking, driving out to an exurban clinic, and spilling her guts in response to the clinician’s blankly voiced form questions, which, in a darkly comic scene, she misinterprets as therapy. She’s committed involuntarily—a danger to herself and others, a diagnosis effectively supported by her increasingly manic I’m-not-crazy protestations, as well as by the tricks her mind plays on her, during which she sees her stalker’s face everywhere.

The film works this vein of ambiguity and self-doubt for only a few scenes. “They got beds, you got insurance,” explains fellow inpatient and wiseass real-talker Jay Pharoah, effectively endorsing Sawyer with a huge red “Not Insane” stamp a la the Michael Jackson episode of The Simpsons.

Unsane is, then, yet another Soderbergh movie about a body that’s become a commodity. In Haywire, Gina Carano’s black-ops mercenary is targeted for termination, and goes freelance in a series of globe-trotting martial arts beatdowns; a handler explains to her about “the ‘halo effect.’ […] It's when an object or work of art is more desirable because of its prior ownership.” Making her live with her body and literally fighting her private sector bosses for her autonomy, her predicament is not so different from that of the sex workers in the more explicitly economically concerned The Girlfriend Experience and Magic Mike.

There’s no Nurse Ratched in this cuckoo’s nest. The head nurse is less battle-ax than bureaucrat, and naps on the daybed in the break room. The regulations and policies governing Sawyer’s confinement are airtight in their banality. The largely anonymous support cast of receptionists and orderlies appear bored, overtired—they’re probably contractors being paid an inadequate hourly wage to just follow orders. The corporate villains are far enough away from the ward to keep their hands clean.

Soderbergh has dealt with the depersonalizing effects of the health care industry, namely in his most gratuitous film, Side Effects, with its whiplash reversals, shocking violence, and hot girl-on-girl action. The characters are permitted to behave as sociopathically as possible, per the terms of the exploitation thriller—and, perhaps, of the pharmaceutical industry. Unsane similarly progresses from tense to trashy, descending—with a big assist from Juno Temple as a trailer trash patient with box braids and shiv—into padded cell psychodrama, and beyond.

What Unsane does first, though, is combine the manipulations of for-profit health care with the more personal emotional abuse of Sawyer’s stalker. When David (Joshua Leonard) shows up in an orderly’s white coat, dispensing Sawyer’s pills and calling himself by a new name, it’s implausible, absolutely—but such capricious storytelling is not exactly disqualifying for a movie about gaslighting. A company is telling Sawyer she’s crazy, and a man is telling her they’re in love. Unsane’s entire narrative is motivated by sadism, chosen consciously.

Like Jessica Jones, Sawyer discovers, in her trauma, her own capacity for cruelty—the word “survivor” seems premature and inadequate. Unyielding in its pacing, functional and fluorescent-looking, and increasingly bloody and bleak in outlook, Unsane is a nasty piece of work, and its nastiness is in no way cathartic. This cynical, disposable entertainment may as well be called Untreated.