Entertainment

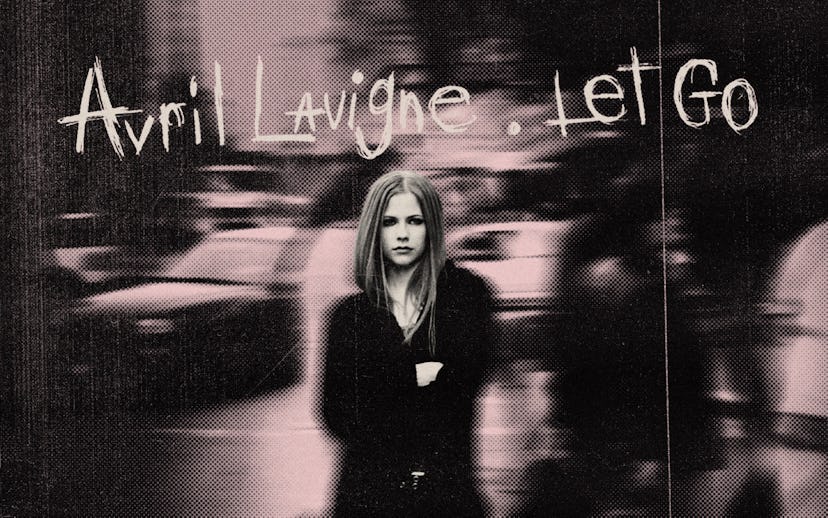

How Avril Lavigne's Let Go Broke The Mold For '00s Teens

2002 was the year of Avril Lavigne.

It’s early 2002. The dot-com bubble has burst and the stock market’s crashing. George Bush gives his “Axis of Evil” speech and signs the No Child Left Behind Act, but I’m eleven and my friends and I are mostly talking about Crossroads and Big Fat Liar. The tabloids are all Britney and Justin and Christina — now Xtina (since the “Dirrty” video). Shaggy’s “It Wasn’t Me,” Eve and Gwen’s “Let Me Blow Ya Mind,” Usher’s “U Remind Me,” and Janet’s “All For You” are fighting to throw Lifehouse’s “Hanging By a Moment” off the charts. Last year, it was all “Thong Song” and “Smooth” and “What A Girl Wants.” This year will be a bit different. It will be the year of Avril Lavigne.

In this last half of fifth grade, my BFF and I are still obsessed with the soundtrack from our favorite movie, Josie and the Pussycats, about a spunky pop-rock band controlled by nefarious record execs — although it’s soon to be tied with The Lizzie McGuire Movie. We are constantly singing “Pretend to Be Nice” in the hallway outside our homeroom and crying about crushes in the locker room and trying to convince our parents we’re old enough to do stuff on our own. We’re reading Princess Diaries and Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and the Confessions of Georgia Nicolson series — stories about teen girls feeling out of place, figuring themselves out. I resent my baby fat and my frizzy hair. I beg my mom for Paul Frank gear. Degrassi: The Next Generation airs for the first time in the U.S. MySpace doesn’t exist yet. We communicate largely via AOL, which we access via dial-up, hogging the family landlines. There is somehow nothing and everything to talk about. Crushes, drama, homework, the new MTV reality show Made, the goofy chapter of the sex ed book we have to read, what’s on TRL and whether we like it or not.

Then, in March, there’s something new. It’s called “Complicated.” The first sounds of the music video are the wheels of a skateboard. A girl in a black tank top and black Dickies and a very loose red plaid tie is riding it. “What’s up boys,” she says, and crouches down with them on the ground of a parking lot. “So what do you guys wanna do today,” asks one of the boys. And the girl, as though she knew what she wanted to do before being asked, answers, “Dude, you wanna crash a mall?” The guys are into it. “Niiiice,” they say. Then the song starts — bright guitars and an “Uh huh/ Life’s like this.”

Her name is Avril Lavigne, she’s 17, and she’s singing about a boy. But this isn’t Mandy Moore’s “Crush” or Jessica Simpson’s “I Think I’m in Love with You.” This isn’t just a song about a boy — it’s a song about appearances. “Chill out, whatcha yelling for?” sings Avril. “Lay back, it’s all been done before/ And if you could only let it be/ You would see/ I like you the way you are/ When we’re driving in your car/ And you’re talking to me one-on-one/ But you become…” The guitars rise, and Avril’s wearing a white tank now, her black bra straps showing. “Somebody else/ ‘Round everyone else…You’re tryna be cool/ You look like a fool/ To me.”

Nothing resonates harder than this. I could sing this about a crush or an ex-friend or the popular girls, or, myself. I’m figuring out who I want to be, how I dress, who I hang out with, what I listen to — how I present to the world. I want to fit in and I want to be cool. Popular, crushable, both cute and sexy at the same time, but also me — whatever that means. This proves difficult. In a cultural landscape saturated with hyperfemininity and tight surfer-girl bods, I feel as though I stand out. I want to stand out, but not too much. Not in the wrong way. I’m just growing boobs but my mom won’t let me buy a bra yet, so I cover them up with baggy tees. The popular girls are wearing tight, layered camis and True Religion jeans and Juicy sweatsuits. I want that, I think, or maybe I don’t. Avril is, in a way, singing about all of this.

It was Avril’s “rocker chick” persona that drew me in. She seemed to transcend contemporary feminine archetypes; she had a lot of guy friends and didn’t care for Starbucks. But it was her simple lines about wanting to be seen as who she was, all the while trying to figure out who she was, that held me. She had a strong public persona — a tough girl, a “tomboy” — and she seemed to express herself unconditionally, through both attire and words. Her 2002 debut album Let Go filled a cathartic void. The gray-and-black disc with the red stencil font stayed in my CD player. Avril was five years my senior, but everything she sang could’ve come straight from my diary. “Sometimes I get so weird I even freak myself out.” That’s what that strange, confused, delighted terror was, feeling like a freak, not wanting to be a freak, wanting to be “Anything But Ordinary,” please. On the yearning bridge of the otherwise plucky “Things I’ll Never Say,” she sings: “What's wrong with my tongue?/ These words keep slipping away/ I stutter, I stumble/ Like I've got nothing to say” — an articulation of how I felt every day at school. “Everything’s changing, when I turn around/ Everywhere I go, all out of my control,” went “Mobile,” one of the poppier singles. That’s pre-teendom, puberty — but also, a post-9/11, pre-Iraq War world, a year that’s been designated the onset of the “digital information age,” the year of the first cell phone with a camera.

Critics wrote that Let Go wasn’t as angsty as it claimed to be, but I beg to differ. “It was really potent for a lot of us,” writes Shamir, an artist who’s spent the better part of a decade challenging genre shoehorning and the notion of “authenticity,” via email. “She expressed a level of angst that everyone could relate to without feeling alienating. She wasn't an average pop girl but she also wasn't fully counter culture.” It wasn’t grunge — so what? Avril had a way of telescoping. Avril got it. “Isn’t anyone trying to find me?” she sings on that moody anthemic single “I’m With You,” sounding not so much lonely as wistfully defiant, waiting to be understood. That’s what we were trying to do, too. Is there anything else that so perfectly encapsulates the feeling of growing up?

Listening to Let Go now feels almost as it did back then — I feel no cringe, no retrospective chagrin, and the memories of lying in my bunk bed, or bopping around on tire swings to “Sk8er Boi,” come flooding back. “I have more memories attached to that album than I do of most other things in my life,” says Ellen Kempner, the musician behind indie rock band Palehound. “[The Try to Shut Me Up] tour was the first concert I ever went to. I still remember how it felt to see an idol in the flesh and experience breathing the same air as them. My dad still has photos of me in a camo shirt absolutely losing my mind in the stands.”

Maria Sherman, author of LARGER THAN LIFE: A History of Boy Bands from New Kids on the Block to BTS (currently being adapted into a documentary by Gia Coppola), agrees. “[Let Go] sounds like the backseat of my mom's minivan, on the Autobahn,” she tells me. “It's maybe the only album that I remember when some of the singles came out, and the order in which they came out — the rest of my life is a blur!”

Let Go came out at the perfect time, especially for kids like us, on the threshold of middle school and looking for an alternative to the Blue Crush Kate Bosworth aesthetic. “I started stealing my dad's ties and wearing them to fifth grade,” Sherman remembers. “It was a turning point in my life, where I was like, ‘Oh, I am also a rock chick! This is my personality now.’ At the time I deeply identified with, ‘Here is a different way to be a girl.’ Because I wasn't blonde, and I was chubby. But I could flat iron my hair and be like Avril — that was accessible to me.”

“I wasn't blonde, and I was chubby. But I could flat iron my hair and be like Avril — that was accessible to me.”

While we were having a blast, experimenting with ways of presenting ourselves, pogo-ing to Avril’s power chords, feeling seen, the critics were having a shit fit. “She's seventeen, Canadian, likes to fight and gets thrown out of clubs. Avril Lavigne won't stop rocking until teen pop is dead,” wrote Gavin Edwards for Rolling Stone. “Ciao, Britney! Skanks — er, thanks — for the memories, Christina,” went Chris Williams’ Entertainment Weekly profile. The way she was written about was beyond condescending. Her use of the word “punk” was hotly debated, derided. “She’s just a product of a major label’s marketing team, she can’t be as authentic as she says she is. She can’t even skate! What a poser,” skeptics would say.

Of course she was heavily marketed by Arista. But if you read the interviews, it’s clear Avril wasn’t what the headlines painted her to be. She balked at the idea of being anti-Britney: “I don’t like that term…It’s stupid,” she says, in the (badly aged, aforementioned) Williams article titled “Avril Lavigne, The Anti Britney,” in EW. “I don’t believe in that. She’s a human being. God, leave her alone!” In an interview with Rolling Stone from October 2002: “Punk is such a touchy word,” she says, wisely. “I go on TRL and all that stuff, and I don't think there's anything wrong with wanting the world to hear my music. Now, so many people have labeled me skater punk…There's more to me than that.” She was more self-aware than most grown-ups gave her credit for. In her Rolling Stone cover story the following March, she told the same writer, Jenny Eliscu: “I might look like a tough chick — and I am — but I'm also a hopeless romantic inside.” It was precisely that simple complexity that made her music so appealing.

It was also her pointed awareness of the way her music and her persona were being picked apart, something any middle schooler now would know intrinsically. As rhetoric professor Mark D. Pepper has noted, Avril never actually telegraphed the I don’t care what anyone thinks message. “Being yourself is only possible precisely because others think about and care about your selfhood too,” he wrote. She was enacting a nuanced cultural critique that went over the heads of those calling her a poser. Avril put words to the catch-22 of self-presentation, and the speed at which life changes. Like on “Nobody’s Fool,” purportedly a jab at Arista, she sang, “If you're tryin' to turn me into somethin' else/ I've seen it enough and I'm over that…I might've fallen for that/ When I was fourteen and a little more green/ But it's amazing what a couple of years can mean.”

In one of the more forgiving professional reviews — of which there were very few — Bill Werde, for the Washington Post, wrote, “Sometimes, the black-and-white perspective of a teenager’s lyrics can get at a fundamental truth.” Chill out, it’s all been done before.

Avril’s influence is indelible. “That album is honestly the reason I do music. I do not know who I would be without that record,” Kempner says. “Once I heard ‘Complicated’ on Radio Disney, I started viewing my instrument as less of a study and more of a tool to express myself with. I finally heard myself in songs. It was the first time I ever really thought that I could write a song or even find my own voice at all.”

Soccer Mommy’s Sophie Allison and Snail Mail’s Lindsay Jordan have repeatedly been quoted speaking about Avril Lavigne’s influence on their music. “That’s how this person came about,” Allison told me, for The FADER in 2018, and Jordan has said to Billboard, “I just wanted to be her so badly.” There’s also the noted fandom of Olivia Rodrigo, Billie Eilish, Rico Nasty, Rina Sawayama, Kailee Morgue, and Ashnikko.

“After Avril, we get Demi, Miley, and Aly & AJ. All of their careers are trickled down from Avril,” Sherman explains. “They're playing guitar, they're wearing chucks and prom dresses, their music is a little angstier and more animated, less singer, they have live bands. [Avril] has influence in alternative realms and then the biggest pop stars of all time.” It’s true — when Let Go ends, the Apple algorithm plays me Miley Cyrus’ “Malibu,” Paramore’s “That’s What You Get,” and Olivia Rodrigo’s “good 4 u.”

“She was my first hero. I was shy and a pushover and she gave me a backbone.”

In the year after Let Go’s release, the whiplash — between her refreshing personality and the poser rhetoric — was severe. We were proffered a different way of being teen girls, and then, suddenly, that wasn’t good enough either. Navigating early ‘00s gender performance was, as Sherman puts it, “messy.” There was a deeper critique happening here that was clearly not apparent to the critical zeitgeist. This kind of double-standard-hinged criticism stretches from Avril to Liz Phair, Lana Del Rey, Megan Thee Stallion, Cardi B, and Billie Eilish. In fact, in 2003, Phair was very loudly scoffed at by critics for “behaving like an Avril wannabe,” as an EW headline put it. The NYT review of Phair’s 2003 self-titled album was titled “Exile in Avril-ville,” because Phair had deigned to work with songwriting team The Matrix, who co-wrote Let Go’s lead singles. Liz’s response to the comparisons, in that very EW article: “Do you acknowledge who you are even if people don’t like you for it?...Should I pretend to be cool so that you will approve of me?” That’s what Avril was saying, too.

There was something different about Avril, hyper-marketed or not. Trend cycles and radio guys notwithstanding, she really did seem to have broken some kind of mold. She was that to us, anyway. “I think of Avril as my first queer icon,” Kempner tells me. “For me, as a budding gay, seeing a girl wearing cargo pants and a backwards hat was like someone gave me the okay to start dressing the way I really wanted to. I would read anything I could about her. In particular I remember an interview where she said that on tour she would order room service and eat it off of her skateboard. She was my first hero. I was shy and a pushover and she gave me a backbone.”

Avril was, and still is, a deeply important figure — musically, aesthetically, culturally. The music itself “was absolutely instrumental in [my] love for pop rock music,” says Shamir. “Let Go perfected the pop rock formula from the ‘90s and brought it into the new millennium in a substantial way.” And her image, her baggy pants and nuanced awareness of teen life, especially on Let Go, hasn’t faded. In fact, she’s been a role model all these years.

Avril Lavigne’s Let Go (20th Anniversary Edition) is out now.

This article was originally published on