Entertainment

The Blessed Madonna On Creating The Dua-Verse In 'Club Future Nostalgia'

The prolific London-based DJ tells the story of how she situated Dua Lipa in the lineage of dance-pop stars.

In 1987, Madonna released You Can Dance, one of the first major remix albums in pop music history. Designed to appeal to the club kids of her audience, the project reworked tracks from her first three studio albums into dance floor-ready bangers. In the years since, the format fell out of favor, but Dua Lipa, along with the prolific London-based DJ The Blessed Madonna, have revived it in all its glory with their ambitious new megamix album Club Future Nostalgia, out now.

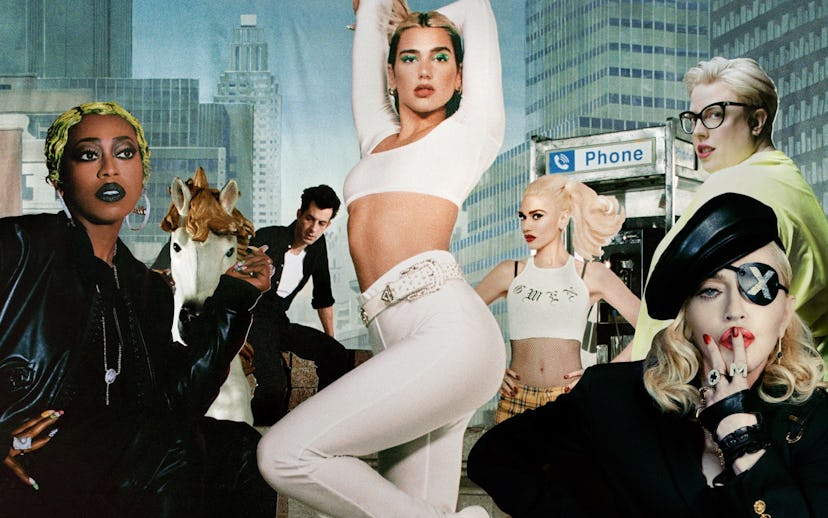

Keeping in the same spirit as You Can Dance, Club Future Nostalgia reworks the disco glitter of Lipa’s Future Nostalgia into a pulsing, underground affair. With a slate of master DJs, legendary guest acts — Madonna, Gwen Stefani, and Missy Elliott appear as new features — along with surprise samples from Stevie Nicks and Jamiroquai, this new and expanded Lipa-verse is meticulously designed to keep you dancing.

The mind who helped put it all together is The Blessed Madonna, a prominent figure in the underground dance/house community. Working closely with Lipa’s team, Marea Stamper oversaw and curated the mix, making sure each of the songs flowed seamlessly into the next, while also imbuing the project with a vital narrative arc. “I knew that I wanted to try to tell the story of women in dance pop over a period in time,” Stamper says. “I wanted to situate Dua in the lineage of women making pop dance songs.”

Over a recent Zoom call from her home in London, Stamper told NYLON the story of how the project came together, what it was like working with Madonna and Missy Elliot, and how a good remix should feel like falling in love with the details. Read it all in her own words, below.

Marea Stamper:

This kind of project, it would have been very possible to sh*t the bed completely. When people love something so much — because Future Nostalgia was the soundtrack of a hard time for a lot of people. Taking it apart, I knew that I was playing with something very precious.

Her team reached out and said, "We have this crazy idea for a mixtape, like an old-school mega mix, like what they would do on the radio ... we want to use samples and we're willing to have all new versions of the songs and features." I ran with that and I got back to them and said, "I could not want to do this any more than I want to do it." I felt like I understood it and they were clearly going for a more underground dance music vibe — [it] did not seem like they wanted EDM. It was really important to me because I don't understand that world at all; it's not my thing.

The idea was that I would curate and work with the team to make those decisions. The first thing I did was make this big, long list of remixers — I just shot for the moon on that. Then it was a list of possible samples. I knew that there would be a couple of songs that I would be involved with directly, and I would remix one song from the album and do one of the new ones. “Love is Religion” had not come out, and so essentially my version was going to be the first one that people would actually hear.

I had some ideas of who the features could be, and I knew that I wanted to try to tell the story of women in dance pop over a period in time. There were lots of touchstones that came into that for me: Madonna, Missy Elliott, Deee-Lite, even Stevie Nicks. I wanted to situate Dua in the lineage of women making pop dance songs.

All of those [intentions] are in there and [Dua actually] sets it out in the beginning. The first thing that she's saying, if you read the lyrics to the song “Future Nostalgia,” she sets the course. [“You want a timeless song, I wanna change the game.”] I knew that I wanted that to be the first track. Joe [Goddard's] remix was really perfect for that because he starts off and the first thing you hear [is] "Future Nostalgia."

Everything went through our mutual teams; there was a process to drop things, and of course there were sample clearances. The most amount of back and forth happened when we were making “Levitating” and “Love is Religion,” both of which had multiple versions. There were discussions as a group about what is the goal of this record? But there was never a point where anybody was like, "Oh I don't like that vibe," or whatever. [Dua and I] texted this whole process and talked on the phone. Our excitement was very similar in some ways, it was like, "Gwen Stefani's going to be in it. Oh my God, Madonna. Oh my God, Missy Elliot."

With “Levitating,” I had to make the whole thing beginning to end as if Dua were the only person on it and then we sent that to Missy and Madonna and then they hopped on it. The second verse in “Levitating” and the backing vocals were replaced by Madonna, which she recorded separately in a studio; those were sent over through her engineer, who is a real hero of mine, Mike Dean. Madonna did different variations on stuff. At one point, it broke out into “Lucky Star” for a second which was crazy. Then Missy just dropped her whole verse and sent it over with the air horn included and it was like... it's exactly as you expect. I ended up Frankenstein-ing these three versions together, then Madonna wanted Mike Dean to mix it all down. So I basically made it and then Mike mastered it and did the mix down on it. It was a great experience.

[About the samples,] they had said that they wanted it to be a mixed tape and that it should have other things in it. What I said was that everything should be in the Dua-verse. That if you just dropped something randomly that didn't have a dialogue with the rest of it, it was going to feel slapdash. It should feel like a welcome bonus that maybe you weren't expecting. There's a section where it breaks out into Neneh Cherry, “Buffalo Stance.” For that to happen, I wanted it to make sense, so I used it first as a sample on “Good in Bed,” where there's a little scratch section and it goes "Gig, gig gigolo." Then I had Mark Ronson call in and request the song so that I could break out into it for a second.

Gwen was a real hero of Dua's. Everything that happens in [Club Future Nostalgia] it's all essentially because it's something that Dua loved. Same thing with Jamiroquai. Jamiroquai was really, from a clubbing point of view, a real touchstone for her. I knew I wanted to get whatever I could do to make it unique. [The Stevie Nicks sample,] I just like her voice first off, but “Stand Back” is a dance record. It was actually meant to run longer, but the eventual version of the song that I got back from Stuart Price [Jacques Lu Cont] cut out the section where the other bits were. I always love it in records when something happens one time and it doesn't necessarily follow form about when you expect it to repeat.

"I wanted to situate Dua in the lineage of women making pop dance songs."

Remixing is like distilling. Maybe you find a point in something [and] you're concentrating a part of it in a way that changes it. The remixes that I love take one little bit of something and loop it in a way that brings a new meaning to it, or isolates a thing maybe that you weren't paying attention to. When I think about the great remixers, they find that moment... Oh, there's a really great remix of “Situation” by Yaz, where there's her little laugh. If you listen to the song you'll hear, there's this little laugh in it. Consequently, that laugh has been sampled a trillion times. It's one of the most sampled sounds in the history of dance music and it's just her laugh.

So there's a moment in Club Future Nostalgia, where I got Dua's laugh and used it in that way. You fall in love with these little details. It's like when you fall in love with a person and there's one tooth that's out of place when you fix up and you love that one little tooth. Remixing is like that little detail in a person, and then just repeating it over and over and over again, or maybe painting it in a different context.

This article was originally published on