It Girl Issue

My Nights Among The Almost-It Girls

Learning to DJ and fending off creeps in the name of fame that looks accidental.

If the dinner party is reaching a lull, I suggest asking a question that has always put a little spice back into my evenings: “Have you ever wanted to be famous?” Among even the closest group of friends, the answers will shock. I’ve used this parlor trick for years, and, from my accrued data, a pattern is forming. Those benefiting from natural charisma will say “absolutely not,” while people utterly lacking star quality will reliably say yes.

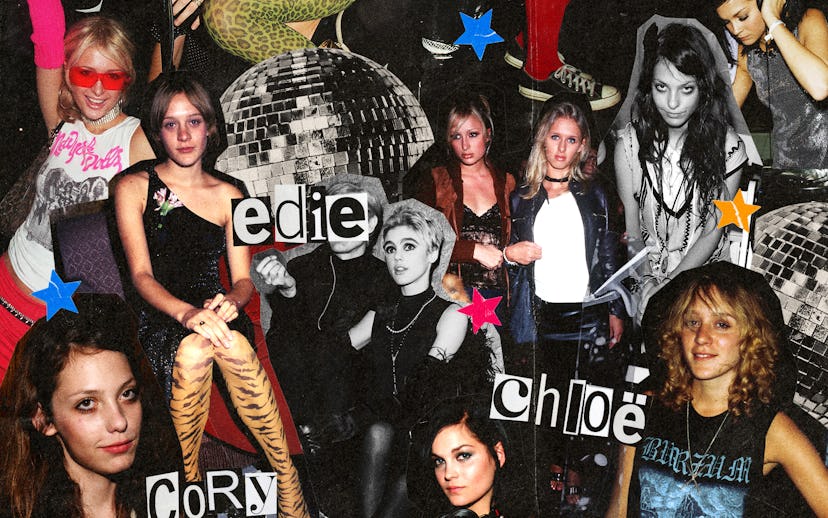

My social experiment offers one theory for why so many present-day A-listers often seem dull. It also illustrates the allure of the It Girl, a young woman — usually thin, white, and rich — who captures the public’s imagination in spite of her reluctance towards fame. Since the 1927 Clara Bow film It (based on the novel by Elinor Glyn) established the archetype, we have come to understand “It” as a quality possessed, not achieved. It Girls are “discovered.” There is an inevitability and myth to them, as well as a passivity. “She just sits there,” artist Rita Ackermann said of Chloe Sevigny in 1994, “but she controls the whole scene. That’s her charisma.”

I always identified as a Party Girl, not an It Girl. (Not that I would identify as an It Girl if I were one: “An It Girl never calls herself an It Girl, because that would be humiliating,” write Kaitlin Gleason and Martha Fearnley, hosts of the It Girl Theory podcast.) But I spent my teenage years and early 20s among the young women being photographed by the right photographers at the right parties. I had a close-up view of the mechanics of what looked like effortless, accidental fame.

This was the pre-social media era, when the Hilton sisters were in the society pages of People, and Leigh Lezark and Cory Kennedy were in blogs and then the culture pages of newspapers. Back then, there was a certain path for teenage girls who grew up in the major cities where being christened an It Girl was in the realm of possibility. Once a fake ID came into your possession, you took on your city under new terms: mapping out the bars and parties that were lenient, the bouncers who turned a blind eye, and the galleries who were always serving bad wine. You stopped going to high school parties, all your friends were suddenly older than you, and you were initiated into a scene.

I remember being disgusted to find out that my photograph had been published as a Vice “Do,” and that I had no recourse to do anything about it. I was 15 at the time. The photo showed me at a party on a school night, dancing with an older boy I had been flirting with at my Toronto retail job, who put his baseball cap on my head. An innocuous moment if undocumented. But the caption was something along the lines of “Why bring your girl to the club when all you want to do is go home and undress her?” Friends told me being a “Do” was what everyone wanted — bucket-list worthy, an affirmation of status and cool. Yet, the caption made me feel icky and voiceless. I did not know the word “objectified.” I hid the magazine from my mother and dismissed it as misguided flattery.

I started using money saved from my part-time job to take the 12-hour bus to New York. At one point, I was 16 and had nowhere to go but the floor of artist Agathe Snow’s apartment in the Lower East Side. (I was told she’d let me stay there because she was “very European.”) I sometimes ended up at the Beatrice Inn, where I was cornered by an “influential” downtown guy who said he’d get me in Richard Kern’s photos if I posed nude. Across cities, creative scenes were still a boy’s club where young women were treated like decoration. Older men were the gatekeepers; they had prominent roles as editors, artists, photographers, and bloggers. They were always trying to steer me around, saying there was “something” about me. It was understood to be a privilege to be taken under their wing. It would make your life easier.

Three weeks after I turned 18, I took the street smarts I had accrued and moved to London. PR dinners and events were foisted on me, and of course I went to consume whatever complimentary food and drink was on offer. I got into DJing — every Party Girl had a DJ phase because it married two of our passions: music you could dance to and free drinks. At 19, I would DJ weekly in London and take the Eurostar to play in Paris, where I once accidentally bumped into Carine Roitfeld while holding two drinks for myself.

I wanted to be an artist, and going out was the easiest way to get attention and propel my career. I documented the endless nights with my camera and recorded what happened in a journal, teetering between subject and object or artist and muse. But when I was no longer compliant with other people’s visions of me, it didn’t sit well with them. What may have once been “plucky” was now difficult. I held grudges and no longer held my tongue when I thought someone was rude or misogynistic. Once, a former mentor and “man about town,” known for giving opportunities to young male artists, got in touch when he visited London from New York. He invited me to see the apartment where he was staying, where he pulled me by the wrists begging for a “massage.” I skipped out of there and never looked back.

Every Party Girl had a DJ phase because it married two of our passions: music you could dance to and free drinks.

As I lost my taste for the scene, I watched girls who had risen during the end of the print magazine era fret that they were suddenly aging out of relevance at the ripe age of 23. They lost their bearings once Instagram came into play, because they had always seen who they were through someone else’s eyes. Now that the microphone was handed over, what were they to say? Would one wrong caption burst their cushiony bubble of mystery? I watched one of the coolest stylists I knew agonize over putting up a photo of herself, almost posting it and then stopping herself, trying to see the image as others would.

Once I was out of the circuit, I felt relieved. I could quietly hone and incubate ideas without feeling like I was missing out on something. It paved the way for an artistic journey on my own terms. Often, I’ve wondered how much of people’s growing impatience with me had to do with the fact that I am non-white and non-monied. “Skinny, rich white girls can act irresponsibly, and it’s seen as ‘flitting around whimsically,’” Gleason and Fearnley write. “White It Girls get judged despite their actions, even romanticized, and we’ve noticed that people of different races that we consider to be It Girls can behave the exact same way [but] aren’t afforded the same luxury or benefit of the doubt.”

Not long after I stopped going out, articles were written with headlines like “How Instagram Killed the It Girl.” Obviously, no such thing happened. Photographing and posting oneself became normal, and it got harder to distinguish whether someone is anxiously chasing fame or truly sharing whatever they feel like. Social media It Girls are still at the mercy of gatekeepers, though a finicky algorithm has replaced the older man lurking in the shadows. It Girls still keep a mysterious air and can be projected upon. We still see them, not what they see.

What has changed is that It Girls now come from all over, and they no longer pretend their fame is accidental. The deception lies in the intimacy they convey. At first glance, the TikTok megastar who posts herself three times a day against the beige walls of her home might seem desperately accessible, but it’s an illusion. Her real life is happening elsewhere, in hotel rooms, over dinner, and at night when things get a little tipsy and she can’t post what she’d like to because it doesn’t “align” with her brand. If she were overexposed, her fans wouldn’t need to track her movements via paparazzi photos and videos, clinging to every morsel of gossip.

And the pendulum of public opinion swings faster than it used to. When I scroll through the comments on the young women who possess even an inkling of It, they vary from extreme adoration (“I’d die to look like her”) to baseless cruelty (“She fell off,” “In her flop era”). A defining It factor is never changing yourself for someone else, and today’s It Girls seem to metabolize fickle fandom in a way my generation would have benefited from. They post through it all. In a culture where young women are guaranteed to be watched and perceived, it’s hard not to savor the small control they have over their own image, authored by themselves. It’s hard not to hope that, one day, when the fog lifts and attention wanes, they’ll tell us what they saw.

—Marlowe Granados

This article was originally published on