Entertainment

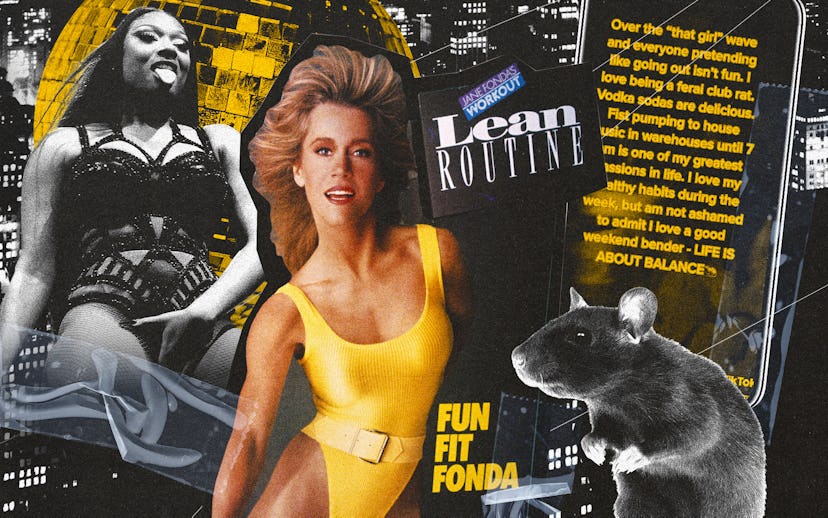

It's The Perfect Time To Revisit Jane Fonda's Iconic Workout

Fonda’s 1982 workout tapes are still a fitting balm for chaotic times, 40 years after they first changed exercise culture for good.

In Y2K treasure Dear Diary, writer and former Vice columnist Lesley Arfin looks back on her punk-rave days of 1997 and manages to touch down in 2022 Bushwick: “Anyway, all these Big Pants Little Shirt people wanted to talk about music, and that can get really f*cking boring, especially if the music you are talking about is drums and bass. ‘Oh yeah I totally love the part in that song when they go brweidwax liwnedfiwex ws xiwneid. Then it slows down and gets all spacey.’”

Culture is cyclical, we know this. Frosted lips. Butterfly clips. Face-framing braids. Popcorn clothing. The “Don’t Be Desperate” Housewives bag I just got from Praying. Gawker is alive and well. House music is back before I even realized it was gone. Like it or not, it’s basically 2002 in this b*tch. We have more reboots than we do normal boots. Pile on three years of pandemic living, and it’s no wonder why the allure of novelty has trended up while most other aspects of life sputter along. Enter: the feral girl.

Its origins are murky at best, but in the context of 2022, it can be traced to March 16, when TikToker Mollie spoke into her camera: “The warmer the weather gets and the longer the days have been getting, I can just feel it. It’s here. It is time for feral girl summer.” By mid-April, magazines were compiling fancams of feral girl summer icons as incoherent as Fleabag, Fleabag’s stepmother, Jessa and Marnie from Girls, and Lucille Bluth. By May, the term had breached the Today Show, where Hoda and Jenna were able to clear the air: “This is somebody who doesn’t care. You can be crazy, undone, wild and free,” said Hoda before the two referenced poems by Anne Lamott and Mary Oliver. The same day, Mollie posted her “thoughts'' on not getting any credit from celebrities and other creators and kept it short: “It’s feral girl summer b*tch let’s get it.”

In June, a piece in the Guardian attempted to establish the feral girl within the lineage of Gone Girl’s “Cool Girl,” to reassert that a true feral girl, unlike other eyeliner-wearing poseurs, comes with an air of superiority, only wears dirty clothes and has dry eyelids (all valid, my lash line is dry as hell). The “Cool Girl” hinges upon the idea of being not like other girls, while feral Girl Summer is designed to let girls exist in whatever ways they may want or need to. It is unconcerned with arbitrating what is or is not feral, fun, or feminist, because that is so beside the point when, in reality, we all owe Megan Thee Stallion money. Summer moments, like these cyclical trends, are both quintessential and unique, owned by the universe. Trying to claim credit for them is as pointless as trying to make them last forever. More important, though, is what we can learn from identifying our influences and cultural foremothers.

Forty years ago in 1982, actor and activist Jane Fonda lived in a world that didn’t want its women to come undone, when femininity was implicitly understood as something effortless, passive. The same year, she revolutionized women’s exercise when she released her first workout home video. In a chapter titled “The Workout” from Fonda’s 2005 memoir, she speaks to these ideas of accreditation and our collectively short-sighted hindsight. Only in writing her memoir decades later was she able to sufficiently credit her friend and colleague for creating the routine that launched the home media industry. In relation to her own sense of due credit, she wrote, “It isn’t easy for me to accept the fact that many young people, if they know me at all, know me as ‘the woman in the exercise video their mother used.’” And now those kids have kids and today’s kids — if they know Fonda at all — might know her best like I do: yelling at Sam Waterston on either Netflix’s Grace and Frankie or HBO’s The Newsroom. Or if you’re firmly Gen Z, you might know her as the rich white woman being gleefully arrested at a climate protest in 2019, which prompted someone on Twitter.com to pipe up about performative celebrity activism. Others quickly bridged the generational gap of understanding. Author of Somebody’s Daughter Ashley C. Ford wrote: “Anybody calling Jane Fonda's activism ‘performative’ doesn't know their history, and is therefore unqualified to enter this arena of conversation.”

I first encountered Fonda in the 2005 rom-com Monster-In-Law where she starred opposite J.Lo. In the opening scene Fonda plays Viola, a white Oprah-type talk show host who has just learned she’s being replaced with someone younger moments before she takes the stage for a milestone episode. With cameras rolling she asks her guest, a teen pop star with stars on her nipples, if she had ever read a newspaper, imploring her to consider what would happen if people forgot the importance of Roe v. Wade. The starlet replies, “Oh, I don’t support boxing as a sport,” causing Viola to scream and launch at her guest, sending the chair legs above both of their heads.

Fonda ends “The Workout” explaining how “moving to the music, the endorphins, the sweating, led [her] to the long slow process of accepting [her] own body. It would also help [her] remain intact during the dark times that lay ahead.” For all of these reasons and more, Fonda is the North Star who can lead us through the final act of feral girl summer, proving there is much to learn from the waves of feral girls who separate and unite the TikTok generation and Fonda over the last four-plus decades.

The girls of 2022 aren’t pioneers of the landscapes on which they wild out. Viruses, bangs, and being messy on the internet are all treatment-resistant, variant-prone strains of life. These trails have been tracked before, the markings still visible in the terrain. In 2008, Arfin published Dear Diary, built out of her Vice columns chronicling her history with heroin, boys, and mean girls. In 2017, Jia Tolentino traced the beginning of the “Personal Essay Boom” back to the same year Dear Diary came out. Amid budget cuts and title shutdowns, the publishing industry found refuge online, amid a sea of possible audiences for and creators of content. Women weren’t just reading glossies like Vogue and Glamour, but suddenly had options like XOJane, Salon, and Gawker at their fingertips — and through the industry’s reshuffling, a new kind of messy girl found herself a place at a table.

In her 2017 memoir How To Murder Your Life, Cat Marnell chronicles the media industry post-2008: mass layoffs, consolidation, the end of company-paid town cars home. In August of that year, Marnell famously took her annual Condé Nast vacation from Lucky to go as feral as you can: flying to Arizona to hang out with a “Garbage Head” in his dad’s house doing opiates and watching Revolutionary Road. Upon returning, she met Arfin at an NA meeting. She quit her job, tired of feeling “like a zombie disaster trying to pass for human in a world where women didn’t even split ends,” eventually having a feral mother-of-invention moment of her own:

“It came to me at the nightclub Kenmare, where I’d been watching party girls apply black eyeliner and check their noses for coke residue in the bathroom. I’d shared mirror space, drugs, and Trident gum with chicks like this for half my life . . .

“Why couldn’t I share beauty advice with them? … Like . . . ‘edgy’ beauty advice for girls who stay up all night and sleep all day?”

Arfin encouraged Marnell to apply at XoJane, where she would rise to popularity as its “resident angel dust aficionado” and become a bold-faced name in the aforementioned Personal Essay Boom, declared dead by Tolentino five years ago. As it came to a close, the influencer rose from the ashes of the once-pristine cover girl. Fast forward to today, we are witnessing the “End of the Influencer” and Coachella in its “flop era” as the new generation of influencers are entering their Cat Marnell era. In the midst of another recession, we see the digital tides turning back with a renewed enthusiasm for a messier — feral — antidote to perfection’s gravitational pull. From Clean Girl Aesthetic to feral girl summer, TikTok’s pivot mirrors that state of women’s publishing at the outset of the digital revolution, capitalizing on that same sense of restlessness.

COVID has only widened the gap between how individuals experience shared reality. There are those going feral from their apartments in the still-real pandemic and the perfectly coiffed celebrities and those wealthy enough to continue to live fabulously in these trying times, while most people fall somewhere between those two universes, balancing having fun, feeling alive, taking care, and staying sane.

Women have been going feral since it was just considered “unbecoming.” Rebelling against puritanical and patriarchal expectations has been mainstream since The Feminine Mistique and second-wave feminism announced that women were seeking freedom from the boxes that limit their comfort and pleasure. And while we are currently in the throes of a Y2K throwback, the first decade of the millennium has been spoken of as a 10-year-long ‘80s revival, so ipso facto it is basically 1982 in this b*tch.

Forty years ago isn’t foreign to our present: a worsening recession with unemployment hitting new highs; unprecedented weather events interrupting regularly scheduled seasonal programming; and a blow to women’s rights was dealt as the ratification deadline for the Equal Rights Amendment expired, which would have constitutionally ended legal differentiations between men and women. The latter has found a renewed sense of political urgency following the Supreme Court decision to overrule Roe v. Wade earlier this summer. The year, as history would have it, was also a huge year for cult-personality white women of the new millennium, birthing Kelly Clarkson, Kirsten Dunst, Liz Caplan, Lily Rabe, Elisabeth Moss, St. Vincent, and Anne Hathaway.

While those icons were in diapers, Fonda had already gone feral. In the HBO documentary Jane Fonda in Five Acts, Fonda recalls being high on dexedrine, a form of speed used as a diet drug, starving herself, binging, and purging on the road as she promoted economic equality across the country with her second husband Tom Hayden in the 1970s. (Coincidentally, the first stimulant epidemic peaked in 1969 and it wasn’t until 2008 — the same year Marnell first checked into rehab — that rates of amphetamine use, dependence, and abuse rose to meet that level again.) Hayden, perhaps best identified as one of the Chicago 7, ran for Congress in 1976, the same year the couple launched the Campaign for Economic Democracy where they worked to promote solar power, environmental protections, and renters’ rights. The actor got her “Klute” haircut from Sally Hershberger, which would be memorialized in her mugshot after being arrested at the Cleveland airport in 1970 on trumped-up drug trafficking charges coming down from Richrd Nixon. By 1982, it was confirmed that she, among other activists, had their phones tapped by the NSA in response to her anti-war efforts. Forty years later, Marnell would walk by the mugshot in the stylist’s namesake salon to get her highlights done, and 10 years after that, it hangs up in my room.

Before long, the sleek mullet unfurled itself into a feathered ‘80s coif. “I do have a tendency to go full-bore, 200% for better or worse,” Fonda said of her activist years. Having shifted away from revering wealth and Hollywood, she found herself living in a commune of sorts — no dishwasher, no washing machine — inviting movement friends over for “dinner,” which was just espresso. Struggling with how best to fund their activism, Fonda landed on her now-famous workout.

Released in 1982, Jane Fonda’s Workout would go on to be the best-selling home video of the millennium. “I had entered my so-called adult life at a time when challenging physical exercise was not offered to women. We weren’t supposed to sweat or have muscles,” she wrote in My Life So Far. The tape changed how Fonda was seen by herself, at home and in the world. She was no longer a star from the big screen, but a fixture in people’s homes. A longtime journalist friend spent time with Fonda on set and noted that he had never seen her lighter, joking side. “[Those friendships] were like a safety valve, allowing a suppressed part of me to the surface.” she wrote. Later saying “[Workout] changed my perception of myself … It was a revolution for me.”

Fonda’s personal revolution moves in the same direction as Marnell’s ouvre, and the feral girl generation: that is, against perfection. From the generation of girls who grew up on sleek editorial spreads, to the next generation of girls raised completely in the age of social media, we have all shared in Fonda’s sentiment of “feeling that if I’m not perfect, no one can love me, but then I realized trying to be perfect is a toxic journey. We aren’t perfect. We have to love our shadow. We have to embrace and accept our shadows and sometimes good enough is good enough.”

Forty years later, that reminder is brought back in the form of feral girl summer. “I just wanted to remind people that your life doesn’t have to fit this perfect mold that we see a lot of other influencers try to portray. There’s not a specific definition. I think it could be different for everybody,” Mollie expanded on Rolling Stone’s podcast.

For me and my friends, the lived-in experience of this concept has consisted of taking 3 a.m. Lyfts there and back for mid dick. Being on the wrong side of the sunrise (which is actually, more often than not, the best one to be on). We are either recovering, getting ready, or going out. We learned how much chaos a single grain of sand can cause (a lot). There’s a chunk of mascara that somehow made it into my Airpods case and has now smeared over months into a Rorschach test I can’t pass. Doing back-to-back vodka shots at the Woods on Wednesday, and watching your they/them-in-crime nearly vomit on the patio. Then at the Dyke March, they tried pulling another friend of mine who informed them that she was freshly scabies-free. There have been sunburnt butt cheeks, rashes from too much molly, unconfirmed UTIs, and Preparation H wipes left on the coffee table when a boy comes over.

Maybe your feral girl summer looks like this, maybe it doesn’t (email me highlights, babes) — I’m not here to gatekeep. Feral girl summer is a moment that, by design, widens possibilities for women and how we want to live. And in that spirit, allow me to put you on, because despite the fact I have been partying more than ever, my ass and midsection are serving a bit harder than usual. Between deep sleeps and having the time of my life, I’ve squeezed in a handful of sessions “doing Jane,” as the girls used to say, each week. And I must say — it’s the exact regimen for those who want to establish a replenishing practice that slides in smoothly between flying high and crashing hard or sputtering around your apartment in the AC avoiding the heat and viruses. Why on earth, in this political climate, would I leave my apartment on a hot garbage New York City summer day to go sweat in a room with strangers when Jane is ready and waiting? The only reason I could think of is that I don’t know she’s there, so that’s why I am sounding the call to all the girls going feral this summer. I’m closer to doing the splits than I have been in years, and I’ve just been doing the beginner’s workout.

Rather than chase a Photoshopped standard, the girls are rightfully re-balancing their f*ck budgets. A modest proposal: reallocate the time and money you spend on a gym membership or barre classes (a cultural descendant of Jane Fonda's workout empire, you know) and funnel those resources into the things that feed the feral parts of your soul — like an entire Costco cake or Beyoncé tickets.

Pony up $10.99 on Apple TV or do Jane for free on YouTube. It works if you’re hungover (or sober). It works if you need something quick before getting ready. The up-tempo backtrack to the video works well as a base for whatever music you want to play on your own (Charli XCX is my recommendation), while still hearing Fonda’s command to “push up” while spreading your legs wide during the video’s glutes section. It all comes together under a simulation-like aesthetic of striped leotards and neon leg warmers, providing the perfect escapist physical activity for anyone feeling stuck in the familiar or daunted by the unprecedented.

If you happen to be Jane Fonda reading this, email me at ck3028@columbia.edu. I want a tattoo in your handwriting (thanks!).

This article was originally published on